Authorities in Abkhazia will grant citizenship to ethnic Georgians willing to ‘change their ethnic identity back’ from Georgian to Abkhaz, the head of Gali (Gal) District administration has said. Applicants should address the Abkhazian president with such a request, he continued, according to Tbilisi-based Civil.ge, who broke the story on 31 July.

Authorities in Abkhazia will grant citizenship to ethnic Georgians willing to ‘change their ethnic identity back’ from Georgian to Abkhaz, the head of Gali (Gal) District administration has said. Applicants should address the Abkhazian president with such a request, he continued, according to Tbilisi-based Civil.ge, who broke the story on 31 July.

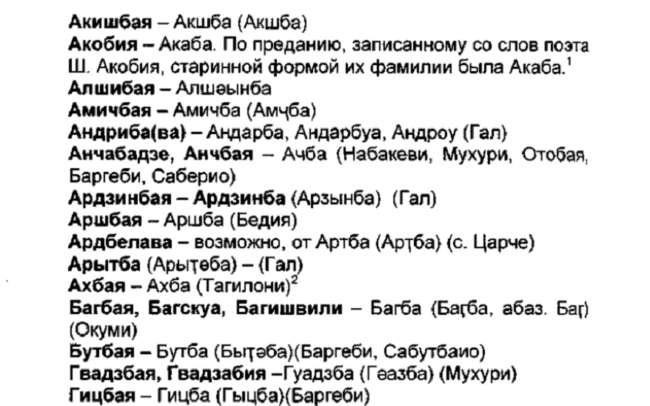

Temur Nadaraya said in his 26 July meeting with the Murzakan Abkhaz Council, that ethnic Georgians wishing to receive an Abkhaz passport would also have to change their surnames to make them ‘more Abkhaz’. ‘You will receive a passport, where the ethnicity will be indicated as Abkhaz and the surname will be written without these modifications which were made during the times of Stalin and [Soviet secret police head Lavrenti] Beria’, he said.

The Murzakan Abkhaz Council, founded in 2014, claims that some of the inhabitants of Gali, who almost all identify as ethnically Georgian, are in fact ‘descendants of Murzakan Abkhaz’. The group’s leaders say that they advocate for the reintegration of ‘Murzakan Abkhaz’ into Abkhazian society.

The term Murzakan Abkhaz refers to inhabitants of Samurzakano (Samurzakan), a historical name for an area of Abkhazia which includes Gali.

According to the council, people in Gali who identify as ethnic Georgians were forced to adopt this identity during the Soviet period.

Edisher Zukhba, the deputy head of the council, read the names of the first 31 applicants, who have been granted Abkhazian citizenship by President Raul Khadzhimba. Zukhba added that they have already identified over 4,500 potential candidates.

The meeting came after the Murzakan Abkhaz Council conference on 19 July, where delegates appealed to the republic’s authorities for the right to change their surnames from Georgian to Abkhaz.

‘During the Stalin period, Soviet authorities forced Abkhaz, especially Murzakans, to change their surnames to Georgian ones, for example, by adding letters “ia”, like from Kedzba to Kedzbaia. In the USSR, they just took away their passports and issued new ones — nobody was ever asked. Today, judging by what was observed at the congress, the reverse process has begun: Murzakans are returning to their origins and to their ancestors’, Caucasian Knot quoted Bota Azhiba, one of the leaders of the council, as saying on 19 July.

Tbilisi’s response

The steps were criticised in Georgia, which considers Abkhazia a part of its territory.

In a statement issued on 21 July, Jemal Gamakharia, Deputy Chair of the Abkhazian Supreme Council — the Tbilisi-based legislature of Abkhazia which has not exercised power over the area since the 1992–1993 conflict — said that ‘unfortunately, the occupation regime in Abkhazia continues to conduct absolutely unacceptable experiments on the Georgian population’ in Gali District.

Gamakharia called the latest initiatives ‘a new form of discrimination against Georgians — an attempt to forcefully change their ethnicity’, claiming that the organisers are ‘shamelessly lying’ about the ‘anti-historical theory as if the population of Samurzakano were forcefully “Georgianised” ’.

Abkhazia’s authorities have faced criticism for their treatment of ethnic Georgians living in Gali. According to Abkhazia’s 2011 census, 98% of Gali’s 30,000 residents are ethnic Georgians; the majority have Georgian citizenship. Many used to also have Abkhazian passports, but these were revoked following a 2013 law, according to which only Abkhazian–Russian dual citizenship is allowed. There are exceptions for ethnic Abkhaz diaspora living abroad.

Residents of the republic who do not have Abkhazian passports face restrictions on freedom of movement, can’t receive pensions, and don’t have the right to vote.

For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status.