Since the beginning of the Second Chechen war, the Chechen authorities, with assistance of the Russian special services, have pressured the relatives of militants. At first glance, the approach has worked. However, the ongoing, albeit sporadic attacks on police, suggest that the nature of this success has been illusory.

Since the beginning of the Second Chechen war, the Chechen authorities, with assistance of the Russian special services, have pressured the relatives of militants. At first glance, the approach has worked. However, the ongoing, albeit sporadic attacks on police, suggest that the nature of this success has been illusory.

This is evidenced by the special operation which was conducted on 11 January in Shali and Kurchaloy districts of central Chechnya.

Law enforcement identified the villages of Kurchaloy, Tsotsin-Yurt, and Geldagan and the city of Shali as areas where dozens of local militants were preparing attacks against the authorities. According to official information, all of them were being prepared under the banner of a local element of the Islamic State. In the course of a special operation in Tsotsin-Yurt and Geldagan, four militants were killed and one was arrested. At the time of writing, one of the militants was still at large, having hidden in a nearby forest. The authorities are currently searching the area. At the same time, more than twenty local residents were arrested, according to the security officials who are directly in charge of destroying the group.

The leader of the group was identified as a resident of Tsotsin-Yurt named Muskiyev. He is the son of a well-known field commander, Isa Muskiyev, who was killed in battle near his native village in 2005. Besides him, four of his brothers were killed during the Second Chechen War. However, in all the time since then, the Muskiyev family, with their young children, did not cause any alarm among the authorities. Their relatives even managed to return to their village, after temporarily residing in the city of Argun. Now it seems that they might need to leave not only their village, but Chechnya in general. Local TV channels have already called for their expulsion. This is one of the authorities’ tactics against the insurgency.

A little earlier, on Sunday, 8 January, a rally by relatives of members of the Islamic State was held to protest against the actions of the organisation’s leader, Abu Bakr al-Baghdadi. About two thousand people gathered in the central square in front of Grozny’s central mosque, the majority of whom were ordinary citizens. The rally was held under increased security. Police were stationed along the entire perimeter in order to inspect all participants.

Many protesters held banners condemning the Islamic State and its leader. According to many relatives of militants, it is propaganda from the terrorist organisation that is responsible for recruiting young Chechens into its ranks.

Many speakers, mainly the militants’ mothers, first apologised to Chechen president Ramzan Kadyrov, and then to the Chechen people, for the fact that their children joined the Islamic State and had committed or planned to commit unlawful acts. Everyone agreed that Chechens are used as tools in global issues and that the nation’s gene pool was in danger.

‘Look at all these conflicts, there [in Donetsk] and in Syria, where Chechens are fighting against Chechens. We are killing each other for someone else’s incomprehensible and unnecessary interests. We need to rethink this. We aren’t immortal. We have suffered three major shocks over the last hundred years: the deportation [of 1944] and two Chechen wars. Can’t we think about it for a moment?’ said Isa, one of the relatives of militants, with his eyes bloodshot, apparently from crying.

The issue of parental responsibility for their children’s actions was much discussed. Many agreed that they were guilty of failing in properly controlling and bringing up their children. Some discussed the need to use physical force against children.

‘If my son doesn’t obey me, then he needs to have his arm or leg broken. It will heal, but he will have time to seriously rethink his actions. We are alien to the values and traditions that exist among Arabs. During both wars, who stood up for us, even if only verbally? Saddam Hussein or Assad did’, said another man in anger, whose nephew was detained while travelling by bus in Nevinnomyssk in Stavropol Krai in order to arrange an attack in Moscow for the Islamic State.

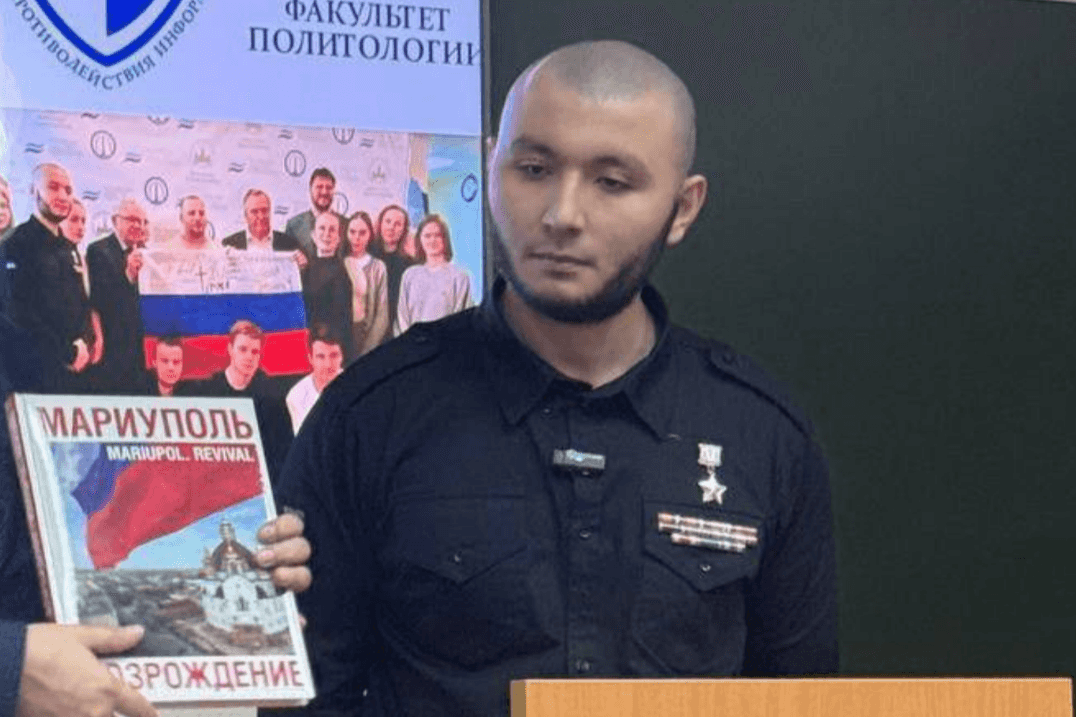

Particular attention was drawn to a statement made by Chechen Said Mazhayev. Several years ago he spent more than half a year in Syria fighting for the Islamic State. After becoming disappointed, he returned home, where he was arrested by the authorities. He was convicted but eventually pardoned, after signing a cooperation agreement, which included becoming involved in propaganda work among young people. Together with NGO activists he travelled across Chechnya visiting schools and universities, warning young people of the dangers of the Islamist ideas of the Islamic State. He may have managed to convince some people, and yet his younger brother Ibrahim, together with his friends, secretly joined the organisation, finding themselves among the group of young people who attacked police and were killed on 17 December in Grozny.

The rally ended with setting posters of al-Baghdadi on fire.

In Chechnya, everyone understands that the point of such rallies is to instruct and frighten anyone who plans to join the ranks of the Islamic State. They show quite clearly that the government won’t be easy on militants’ relatives, and the least they’ll have to endure is public penance for the actions of their children. Worse still, they can become the subjects of a blood feud with the relatives of their children’s victims, and they’ll be expelled from the republic, without means of subsistence.

The pressure being exerted on relatives of militants isn’t a new phenomenon. As fat back as the Russian conquest of the Caucasus in the 19th century, dozens of Chechen villages together with their residents were burnt down and destroyed by order of General Aleksey Yermolov, but the current scale is unprecedented. There are numerous videos online from the state TV channel, where the authorities force parents to curse their dead children in public, standing over their bodies.

There is one sensational story of an elderly resident of the town of Shali named Danilbek, who refused to curse his son and instead blessed his death in the presence of the head of the of Shali District Police, Magomed Daudov (now Chairman of the Parliament of Chechnya). For his impertinence, he was badly beaten, in front of his relatives. The old man, who has lost four sons during the wars in Chechnya, suffered a heart attack as a result of the beating. His relatives took him to Moscow for treatment. He now lives in Europe.

The Chechen authorities are very selective regarding their choice of people to terrorise for the actions of their relatives who took up arms. All close relatives on the paternal side, all the way up to second cousins, are subjected to strong pressure. Intimidation and beatings become common. The Prosecutor’s Office and the Investigative Committee of Russia are obliged to prevent such crimes, but instead they pretend not to notice them. None of the persecuted families wish to file written complaints to the prosecutors. If they did, they assume, they would face even greater terror.

Five or six years ago, in areas where there were still militants hiding in the mountains of Chechnya, the authorities forced close relatives of the militants to walk in front of the police and soldiers during special operations. This tactic was first used during the Russian conquest of the Caucasus. Even in 1976, when the last Chechen abrek (anti-Russian guerrilla fighter), Khasukha Magomadov, was killed, his brother was put at the forefront of a number of police and security forces during the operation. He was forced to go first towards the emaciated 71-year-old Khasukha, who was hiding in a mountain cemetery in Shatoy district, hoping that brother wouldn’t shoot at brother, and if so — he would become the first victim.

Chechnya’s president Ramzan Kadyrov favours this tactic today. It was on his orders that brothers and fathers were driven into the forest in order detain or kill their militant relatives.

Cruelty and collective family responsibility on the part of the authorities are among the reasons which led many Chechen fighters to travel outside Russia to Syria, and to participate in the conflict in the ranks of the Islamic State. It may seem on the surface that the Kremlin’s dream of subduing Chechens has come true, but the reality is more problematic. The Chechenisation of the conflict, i.e. making Chechens fight against Chechens, is bound to backfire eventually. Chechens will not forgive other Chechens’ mockery, abuse, and cruelty to the innocent. Their hatred towards the perpetrators and their helpers will be expressed in silence, for now. A Chechen’s silence, while they’re holding inside a deathly offence, is often more eloquent than loud speeches. No-one knows when or where, or even in what generation, but this resentment will eventually explode.