Opinion | The ECHR’s verdict is in: Merabishvili’s detention was politically motivated

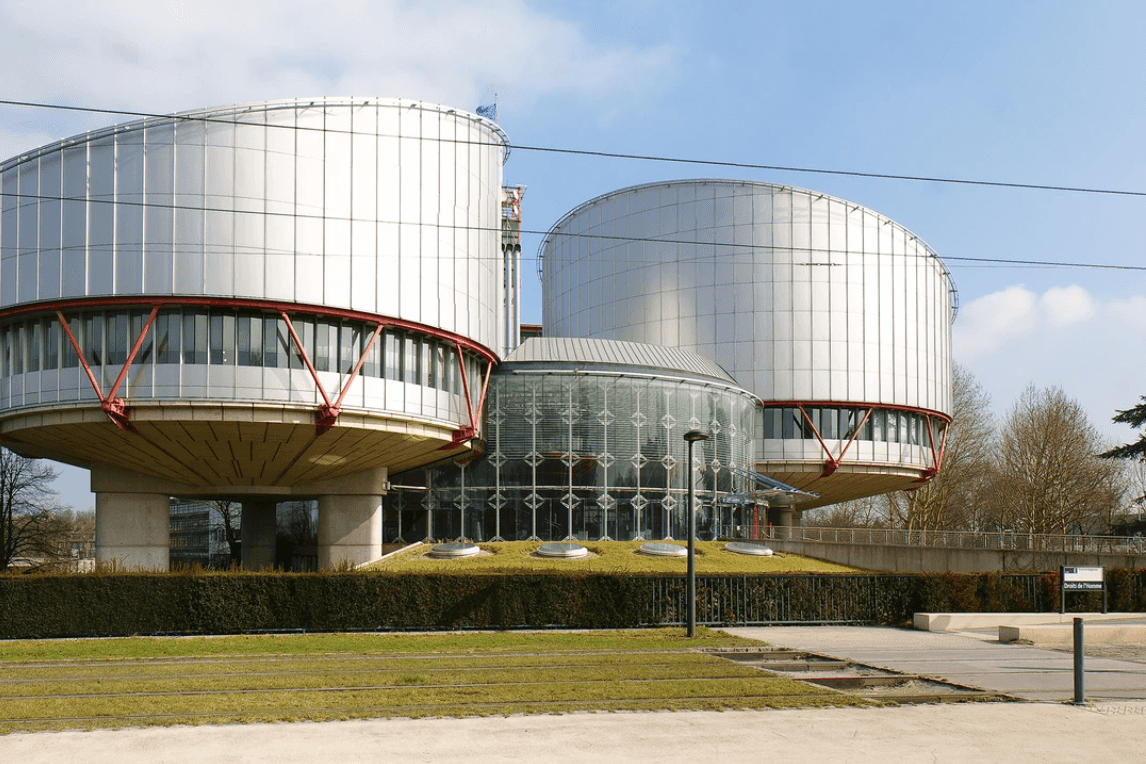

On 28 November 2017, the European Court of Human Rights in Strasbourg ruled in the hotly awaited case of the detention of Ivane Merabishvili, the former Georgian Prime Minister and Interior Minister. The judgment, the second on the case after the Georgian Government challenged the first, had been the subject of much interest in Georgia and abroad. This is hardly surprising not only given Merabishvili’s previous life in Georgian politics, but also the global phenomenon of politically-motivated proceedings.

[Read on OC Media: ECHR: Georgia violated rights of former PM Merabishvili]

The Georgian Government was clearly found by the Grand Chamber, the highest body of the Court, to have misused its power against political opponent Merabishvili. The Court reiterated that there were political motivations behind Merabishvili’s pre-trial detention, and that it was misused to exert pressure on him, in breach of the international human rights standards which Georgia is legally bound to follow.

So what happened?

Merabishvili was arrested and detained in May 2013 charged with a number of criminal offences. On 14 December 2013, he was taken from his Tbilisi prison cell in the middle of the night, and, with his head covered, was driven to an unknown destination where he was questioned by the Chief Public Prosecutor of Georgia and the head of the Georgian prison service. They offered Merabishvili a deal: to provide information about former President Mikheil Saakashvili and the death of former Prime Minister Zurab Zhvania, in exchange for a guarantee that he would be released and allowed to leave the country with his family. Merabishvili refused to comply and was threatened with worsening prison conditions. He was convicted and sentenced to five years’ imprisonment shortly afterwards.

What does the judgment mean?

Despite the Grand Chamber’s judgment in Merabishvili’s favour, the Government has attempted to present the case as a win; it is anything but. Throughout the proceedings and to this day, the Georgian Government has maintained that the incident on 14 December never occurred. However, the Grand Chamber was clearly unpersuaded by the Government’s evidence.

It is striking that surveillance footage from an establishment as prone to violence and accidents as a prison would be preserved for a shorter time frame than footage from road-traffic cameras. — A quote from the judgment

Crucially, it believed Merabishvili’s account of the night in question, finding it to be ‘detailed’, ‘specific’, ‘consistent throughout’, ‘sufficiently convincing’ and ‘proven’.

In comparison, it expressed serious doubts about the Government’s evidence, including its purported investigations into the events of 14 December, and especially its assertion that video surveillance footage of the prison — which could have conclusively proved or disproved Merabishvili’s account — had been automatically erased and the fact that it took almost three years to obtain evidence from key witnesses.

The authorities’ initial reaction to the allegations […] was to issue firm denials […] and the ensuing inquiry and investigation were, as already noted, marred by a series of omissions from which it can be inferred that the authorities were eager that the matter should not come to light. Thus, the main protagonists […] were not interviewed during the inquiry but only in the course of the investigation, in September 2016, nearly three years after the events, and the crucial evidence in the case — the footage from the prison surveillance cameras — was not recovered. — The Court’s Grand Chamber

The Court concluded that the reason for Merabishvili’s detention had changed since he was first imprisoned in May 2013. Whilst his arrest and detention could originally be justified, the incident of 14 December showed that later, the predominant (and improper) purpose for his detention was to obtain information about Saakashvili and Zhvania and to exert pressure on him, in violation of Article 18 of the European Convention on Human Rights (ECHR), the object and purpose of which is precisely ‘to prevent the misuse of power’.

In addition, despite the Government’s assertion that the judgment was simply concerned with the events of December 2013, the Court held that by 25 September 2013, four months after Merabishvili was detained, his pre-trial detention had ceased to be based on sufficient grounds. This breaches the requirement for an individual to be released pending trial unless the authorities can show that there are reasons to justify further detention (Article 5(3) ECHR).

What next?

The Grand Chamber has paved the way for individual victims of politically motivated detentions and prosecutions across Europe to challenge state abuse of power more effectively. This is a landmark judgment resetting the Court’s case law on politically motivated proceedings. As we argued during the hearing in March 2017, it is frequently impossible for a person to directly prove that the aim of their detention or prosecution is political. The Court held that it will closely scrutinise the explanations of States and draw inferences from indirect evidence, as it has done in Mr Merabishvili’s case. — Professor Philip Leach, EHRAC Director

The finding of political motivation by the Court is so rare and carries such weight that there is now an onus on the Georgian authorities to instigate a rigorous, independent investigation into Merabishvili’s covert removal, and if necessary, to re-open the proceedings against him, a process which might justify the quashing of his conviction. To date, the government has failed to acknowledge that the events of 14 December ever took place and there has been no meaningful or effective investigation into what happened or who authorised it, or anyone held accountable.

Why does it matter?

Beyond Merabishvili’s personal situation, this case also has ramifications for Georgia and for other countries with, as the Georgian Judge Nona Tsotsoria put it, in her joint concurring opinion, ‘no traditions, or limited traditions, of peaceful power transfers’. In her view, supported by Judges Yudkivska and Vehabović:

Any long-term democratic stability requires a track record of and a commitment to rotation in office. This aspect is particularly problematic for new democracies, the majority of which, more than two decades following the collapse of the Soviet Union, are still characterised by their almost invariably deeply fragile nature, with political structures that are porous to anti-democratic elements. While the relevant national laws may be in line with Council of Europe and other international standards, their application by both the executive and the judiciary is frequently not […] Article 18 needs to be preserved as an effective and instrumental protection mechanism for prohibiting the misuse of political power and for limiting the use of specific restrictive measures for improper purposes. — The Court’s Grand Chamber

Merabishvili is just one of a growing number of people, including politicians (e.g. Yulia Tymoshenko and Yuriy Lutsenko), ordinary citizens, human rights lawyers and media outlets across the former Soviet space who are subjected to politically-motivated detention and prosecution. For example, EHRAC also represents Azerbaijani human rights defender Rasul Jafarov. His arrest and detention were found to be politically motivated in March 2016, leading the Council of Europe’s Committee of Ministers to call on the Azerbaijani government to re-open his conviction. The Court’s judgment in Merabishvili’s case shows that governments will be held to account for their actions and for using their power for ulterior purposes. Such practices are fundamentally undemocratic.

Ivane Merabishvili is represented by the European Human Rights Advocacy Centre (EHRAC, Middlesex University, London) and Otar Kakhidze (Georgia). They also represent former Mayor of Tbilisi, Giorgi Ugulava, in a similar case.

The opinions expressed in this article are the words of the author alone, and may not necessarily reflect the views of OC Media’s editorial board.