In the villages around Armenia’s Lake Sevan, for up to 10 months of the year the men work away in Russia to earn enough money for the family to survive. This leaves the women alone to complete the back-breaking farm work — and the children growing up without their fathers.

In the villages around Armenia’s Lake Sevan, for up to 10 months of the year the men work away in Russia to earn enough money for the family to survive. This leaves the women alone to complete the back-breaking farm work — and the children growing up without their fathers.

[Read in Armenian — Հոդվածը հայերեն կարդացեք]

Thirty-three-year-old Khatun Zhamaryan hauls heavy equipment over her potato field to treat the crops against harmful insects. She works during the hottest time of the day because the heat brings insects out from under the ground. It’s hard work, but she is not dejected. Nothing disturbs her from her work — neither the heat, nor the drops of sweat falling from her sunburnt brow.

Khatun lives in the village of Yeranos, on the shores of Lake Sevan in Armenia’s Gegharkunik Province. Although the village has an official population of 6,000, practically the only people left in the village at this time of year are women, the elderly, and children. They cultivate potatoes and cereals, and rear livestock, and the burden of all this heavy work falls onto the shoulders of the women.

Thirty-five years a seasonal worker

Khatun’s father-in-law, 70-year-old Suren Nerisyan, worked for 35 years as a seasonal labourer in Russia. He says that the tradition came about during Soviet times, when men in the village would go to Russia in the summer to work and would return home in the winter. Since the collapse of the Soviet Union, all the men in the village have continued to follow this path.

‘My three sons work in Sverdlovsk [in the Russian Urals]. For so many years they have been going to that town, while their wives and children stay at home. They can’t take [their families] with them because all the men live together in one large room. A few months will cost them nothing, and what else can be done? If they stay here then who will take care of all of us?’ he tells OC Media.

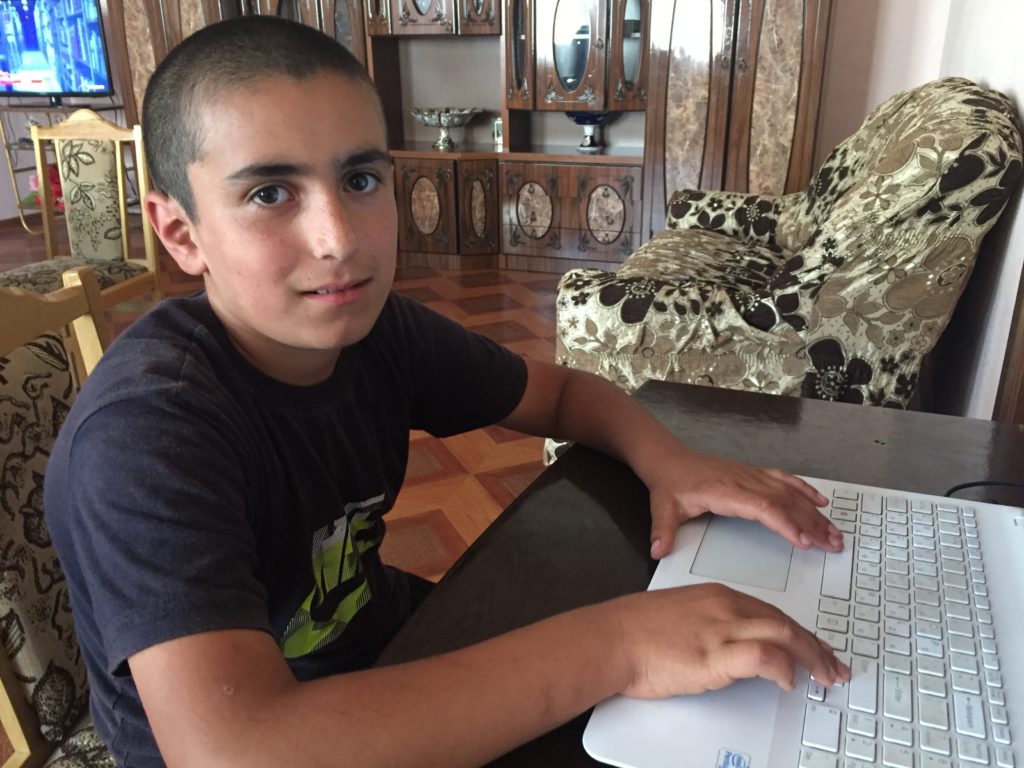

In a corner of Khatun’s guestroom there is a computer. Twelve-year-old Liparit and nine-year-old Adam use it every day to talk with their father on Skype.

Khatun’s 65-year-old mother-in-law, Zhena, is against the family living apart for 8 months of the year. ‘Do you know what my grandson says? He says, “Is that really dad? My mum is both mum and dad for me.” ’, she tells OC Media.

‘This time I said [to my son], either take your family with you, or don’t go — I mean what kind of life is it to live apart for so long and not see each other?’

Yeranos is not unique. In practically every village in the district a similar situation exists — the men travel for seasonal work and return towards the New Year.

Love over Skype

The village of Artsvanist lies 28 kilometres east of Yeranos and has 3,600 inhabitants. During the harvest season, all of the women and children are engaged in agricultural work. Thirty-four-year-old Tatev Petrosyan works in the field with her 15-year-old daughter, Ghayane, and 13-year-old son, Karen. She says that after she got married her husband started to work away during the summer. When the children were small, they would need time after their father returned to recognise him and get used to him again, she says.

‘We mainly talk over Viber or Skype. We live together for two or three months of the year….the rest of the time we are apart. The children live without their father’s warmth and care. And we are forced to do the agricultural work ourselves. The women and children have to do all of the work, and it takes from us all of our strength and our health. I have injured my spine from this heavy work’, says Tatev.

Tatev’s husband has gone to work in Russia with three of his brothers — two went to Moscow and two to Krasnoyarsk. The women complain that their husbands often do not send back any money for months because their employers do not pay them on time. While waiting for money from their husbands they are forced to live off social welfare payments or their meagre pensions which their elderly dependents receive.

‘The money from social welfare and pension together comes to just ֏58,000 ($110) a month, out of which we pay ֏15,000 ($30) for utilities and then have to live off the remainder for the rest of the month. There is not a family in the village which hasn’t taken a loan from the bank. We took a loan of ֏300,000 ($600) so that my husband could go to Russia. And then from there he sends money back to pay off the loan. And round it goes like a carousel’, Tatev says with disappointment.

One-hundred-thousand migrants

In the opinion of demographer Ruben Yeganyan, economic migration is the only rational way for many people to provide for their families.

‘Today, the number of seasonal workers alone stands at 80,0000–100,000. Eighty-five percent of them are men, mostly young men’, Yeganyan says. ‘Russia is the destination for the vast majority of them (95%)’.

The deputy head of Armenia’s Migration Service, Irina Davityan, notes that according to official statistics, the number of families affected by migration is rising. While in 2007–2013 this was 24% of families, in 2012–2015 this rose to 34%.

‘Despite the devaluation of the rouble, which makes the issue more complicated, our compatriots still go to Russia for work and this has not changed things’, says Davityan.

As a result of the economic migration from Armenia, a new model of Armenian family has formed whereby women live for 10 months of the year without their husbands and where children are deprived of fathers.

Tatevik Bezhanyan from Return and Protect, who support Armenian migrants and their families, notes that when interviewing economic migrants for studies, they say that if they could earn even half of what they do in Russia in Armenia, they would not go abroad, as their absence has a very detrimental affect on their families.

‘It is left to [women] to raise the children, and in rural regions, it is left to them to do all the heavy agricultural work. As a result of this, the man’s social role in the Armenian family has diminished. The father of the family has his role reduced to providing money and nothing more’, explains Bezhanyan.

The village of women

Next to Artsvanist lies the village of Tsovinar, with 5,000 inhabitants, which is famous for its high number of economic migrants. Twice a month buses depart from the village with migrants bound for Russia.

Forty-seven-year-old Levon Zakaryan is one of only two men in the village who after getting married did not start going to Russia.

‘I cannot leave my wife, children, and elderly parents. Of course it’s hard to compare the wages in Armenia with the wages in Russia, but I am determined to stay and work in my native village. During Soviet times, in our village and in the neighbouring villages, there were plants and factories which provided employment. Agriculture is not profitable — there is hail and then there is drought…’ says Zakaryan.

Next to Zakaryan’s plot of land lies 42-year-old Ishkhan Taroyan’s potato plot. He also maintains that if it were possible to earn a living in the village, then not a single man would want to leave his family and go abroad.

‘Apart from Levon and myself, there are no other men left here’, he laughs. ‘From here they go to Bashkiria, Tatarstan. There are good businessmen from our village who live there and who provide our villagers with work that pays well. There they can earn ₽40,000–₽50,000 ($670–$840). But potatoes do not bring in that kind of money. Now you can compare — which is better?’, Taroyan says.