Stella Adleyba, 26, OC Media’s correspondent in Abkhazia.

‘When the war in Abkhazia began, I was only a year old. My Dad went to the front in the first days of the war, so we were left alone: my mother, my brother, and me. Of course, I don’t remember what happened in those days, but all of my life I have listened to the stories of my mother and brother about what we went through back then.’

‘When the war in Abkhazia began, I was only a year old. My Dad went to the front in the first days of the war, so we were left alone: my mother, my brother, and me. Of course, I don’t remember what happened in those days, but all of my life I have listened to the stories of my mother and brother about what we went through back then.’

[Read in Georgian — სტატია ქართულ ენაზე]

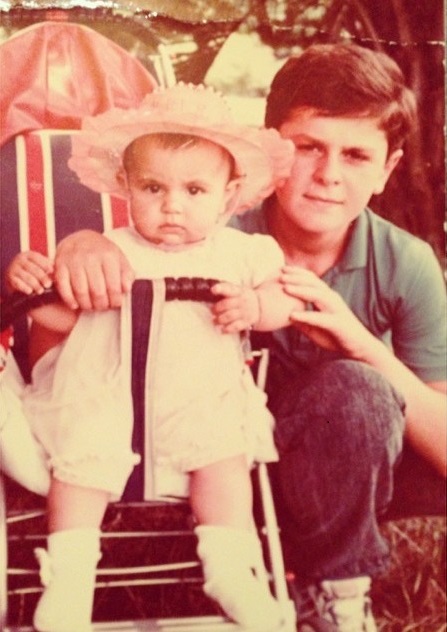

‘Two months after the outbreak of the war, on 22 October, something happened that changed my life. On this day, my 12-year-old brother and I were with my grandfather and grandmother in their village. Dad came home from the front to see us and my mother was in the city. We had a big yard in that house and my brother loved to push me around in a stroller around it.’

‘Two cars drove up to our gate, and Georgian militiamen came out. There were about 15 of them, and they all headed towards our house. As my brother tells me, they were not in a normal state, and their eyes were like glass. Most likely they were on drugs. As if not noticing us, they passed by into the house.’

‘They led my father and grandfather out of the house with machine guns to their backs. Grandmother ran after them in tears, but at that moment she could change nothing. They were put in a car and taken away. My brother took me into his arms, and we stood watching them. This was the last day we saw my father and grandfather, and the last they looked at us.’

‘I wish them to live and suffer every single day’

‘Their bodies were found three days later. Only when I grew up did my mother tell me in what condition they were in. Their bodies had many gunshot wounds, their fingers had cuts on them, and it was obvious that they had been run over with a car. This is why my mother did not immediately recognise them.’

‘They were killed cruelly and in cold blood. It’s very difficult for me to think about it, it’s terrible to imagine what they were feeling. The actions of their killers cannot be justified. I do not wish them to die, but I wish them to live and suffer every single day.’

‘Mum was left alone with two children, while the war was raging on. She says it seemed to her that the worst had already happened. But there was a new trial in store for us.’

‘Since our father fought in the war, the killers saw his family as enemies as well. After a while, they came back for us.’

‘She covered my mouth, so they wouldn’t hear me cry’

‘When the murderers came back, my brother hid, and my mother took me in her arms and ran into the forest. We were lucky that our house in the village was not far from it. They saw that she was running away and went after her.’

‘Mum says she ran so fast that she did not even notice how she jumped over a metre-tall fence. She managed to hide in a hole in the ground. She covered my mouth, so they wouldn’t hear me cry.’

‘They never found us that day, but they burned our house to the ground along with all our possessions, and we were left with nothing. We spent the whole day in the forest. When they started looking for us, my mother heard the voice of our grandmother calling us, but she did not answer, because she was afraid the murderers would come along with grandma.’

‘She had to be strong — there was no other way’

‘The war continued, and we lived with our friends. Mom tried selling things to feed us. She bought some cheese from an old lady, and then resold it. This is how we were surviving.’

‘When the war ended, it seemed to everyone that a new life was beginning. But these were just illusions. My father was gone. My grandpa was gone. And there was another blow about to strike our family again.’

‘My mother’s brother was helping unload grenades left after the war. As he went through the weapons he accidentally took a grenade that exploded in his hands, which detonated all the other grenades. Of course, my uncle died.’

‘It was another shock for everyone. Mum says she did not want to live at all. But she looked at me and my brother and realised we had no one else but her. She had to be strong — there was no other way.’

‘Everyone survived as best they could’

‘In Abkhazia, people’s lives are still divided into before and after the war. Living after the war, you just don’t know where to go. Familiar streets and houses stand in ruins, people you used to meet walking on the street are no longer there. And you yourself have changed as well. It will never be the same.’

‘The post-war period in Abkhazia was very difficult. We had no house, no documents, and no clothes. We had nothing to eat. Were it not for humanitarian aid from various international organisations, many would probably have starved to death. There was no work and everyone survived as best they could.’

‘I often recall situations from my childhood, for example, when I wanted a toy or food, my mother often could not buy it for me. I remember that I was about six years old when the first Barbie dolls appeared in Abkhazia. I asked my mother to buy me such a doll, but she simply did not have the money. I was hurt.’

‘Of course, I remember all this with a smile, but I still feel some pain in my heart. Now I apologise to my mother that I was nagging her about these things. After all, she was much more hurt, because she could not provide her child with everything.’

‘I still have a lot of resentment in my soul’

‘Despite all the difficulties, my mother was able to raise us and give us everything that was in her power. Today, my brother and I are self-sufficient and can afford what we could not before. I like to travel and explore the world. I could even afford to buy a whole house full of Barbies.’

‘I got married. It’s almost like a fairy tale, but I still have a lot of resentment about this war in my soul. At my wedding, I thought about my father not being there to see me in my wedding dress.’

‘I imagine that he looks at me from above and rejoices at my achievements. But the pain is there, because it’s impossible to change anything. Only other children of war can understand me, those who were in the same situation as I was. Every memory of the war makes me cry.’

‘Often I ask myself: What if none of it had happened? After all, we could live a different life, my dad would be next to me. And I love him so much. Perhaps, I would not have become a journalist and would not be interested in conflictology. It really could have been different. But alas.’

‘So many destroyed lives’

‘I’m not a nationalist. I believe that there are normal people among Georgians too, because a normal person wouldn’t kill his neighbour just because of their nationality. But the thought that somewhere on Georgian soil the killers of my family are walking makes me incredibly angry.’

‘If I met them, I would probably not flinch before killing them. They do not deserve forgiveness. So many broken fates, so many destroyed lives — this we will never forget!’

‘No matter how much I try, I cannot forgive these people. After all, they deprived me of the happiness of growing up in a complete family. They took away my father’s life, and with it, they forever changed mine.’

[Read a voice from Georgia: ‘I am not angry at Abkhaz people’]