Despite tightening laws against early marriages in Georgia, among the country’s ethnic Azerbaijani population, they remain common. The results of such marriages are often tragic, with young girls leaving education, becoming victims of domestic violence, or in some cases, dying.

‘I lost the game of life the day I was born. When I was born, my parents promised me as a future wife to another family. I was raised hearing about it, and when I turned 15, I got married. Nobody asked my opinion’.

Sanubar (not her real name), a resident of Mskhaldidi, a village 18 kilometres from Tbilisi with a predominantly ethnic Azerbaijani population, was one of the hundreds of young girls who marry at an early age every year.

The 17-year-old shakes the cradle of her one-and-a-half-year-old child with her hands, talking about how she was forced to get married to a man she did not love.

‘Who was I to contradict them? The only time I told my father that I didn’t like the man was before the engagement. And my father said that I had to marry him anyway because he had given his word as a man promising me as a wife. Since that moment, I have kept silent…’

Because of her age, Sanubar is not officially married. Nine other people live in the house where she was brought as a bride. It is a heavy burden on her fragile shoulders to be in the service of such a large family. She says she often has conflicts with her mother-in-law for not being able to manage all the housework.

Most underage marriages go unreported

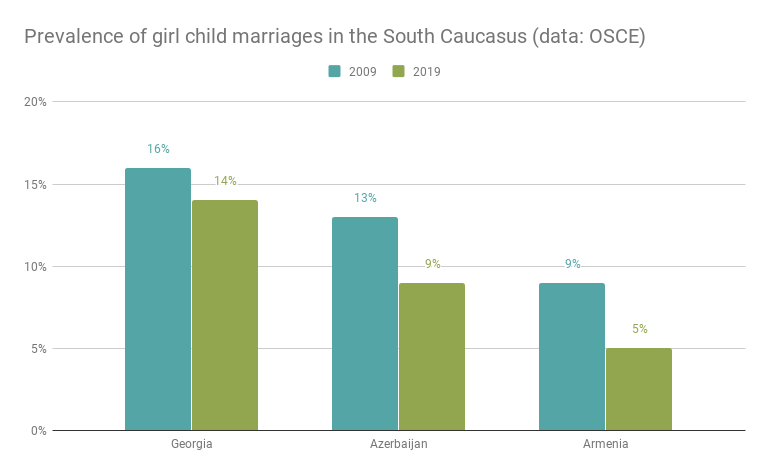

According to the latest Gender Index published by the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in May 2019, 14% of girls in Georgia aged 15–19 had been married.

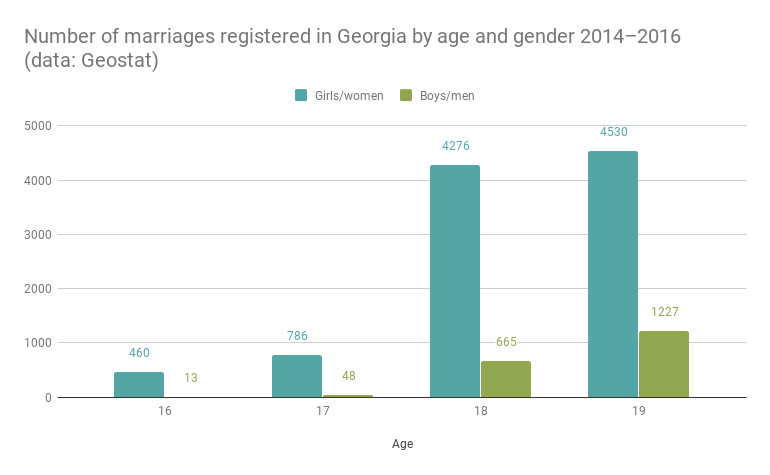

While the Georgian Public Defender, in its annual human rights report of 2018, noted that most underage marriages are not registered, they found that 738 minors became parents. Of those, 715 were women and 23 were men.

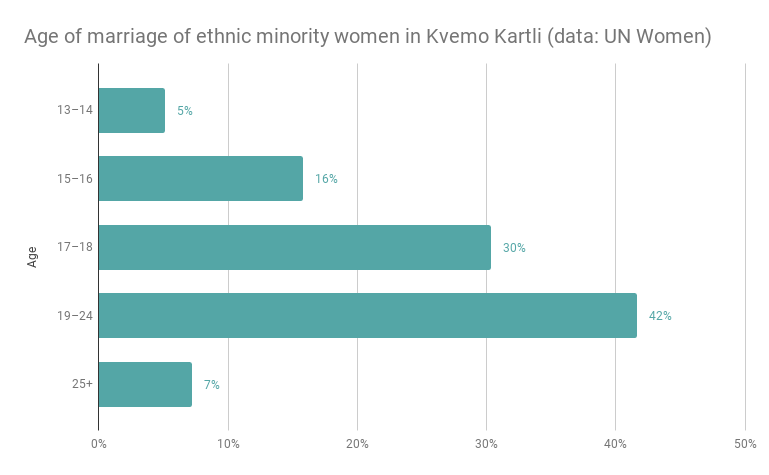

A UN Women study conducted in 2017 in Kvemo Kartli, a minority region dominated by ethnic minority groups in Georgia, including Azerbaijani, Armenian, and ethnic Russians, asked women how old they were when they got married or started to live with a partner. The study found that 32% of married ethnic minority women had married before turning 18. Of these women, 5% were married between the ages of 13–14, while 16% married at 15–16.

Samira Bayramova, a sociologist at international humanitarian organisation Mercy Corps, says that the number of early marriages in Georgia is continuing to grow despite the tightening of laws and toughening of punishments.

‘Unfortunately, our sociological surveys show that in the last two years, an increase in the number of early marriages has been noted. Apparently, neither the toughening of the law nor the penalties can prevent these traditions ethnic Azerbaijanis have practised for hundreds of years’, she says.

Dropping out of school to get married

Nubar Bayramova, a 27-year-old Georgian teacher working at the Nazarali village school in the Gardabani Municipality, says that Azerbaijanis, as a rule, do not let their daughters go to school after the eighth grade.

‘There was a girl whose parents took her out of school in a class where I used to teach. The girl was asking me to help her. After talking to the head teacher and other teachers, we decided to stop it.’

‘Even though her father avoided meeting us, we met and talked to her mother many times. Unfortunately, we failed to achieve any result, and the girl was forced to get married shortly after. In the 12th grade class where I teach at the moment, seven to eight female students already have their own families’, says Bayramova.

According to the Public Defender’s 2017 report, in 2016–2017, around 5,700 students dropped out of school early. The highest number of dropouts were seen in Tbilisi, Kvemo Kartli, Adjara, and Kakheti.

‘In Tbilisi, this might be attributed to the high population, but the indicators for Kvemo Kartli, Adjara, and Kakheti require special attention because, judging by referrals to the Public Defender, these are the regions where early marriage and work account for a large share of the dropouts’, the report reads.

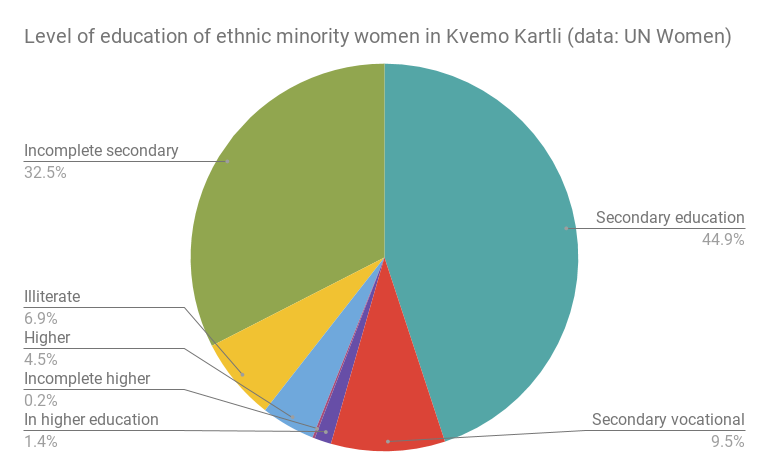

According to the UN Women study, almost 40% of ethnic minority women in Kvemo Kartli did not complete secondary school, with 7% being illiterate. The number who graduated from a higher education institution was drastically lower, at only 5%.

School attendance is monitored by the Social Service Agency. However, comments by Levan Gogadze, the deputy director of the agency, suggest that social workers have little power to force parents to send their children to school.

‘Under the law, if a minor does not come to school for some time, the school applies to the Social Service Agency and our social worker meets with the family and advises both the child and their legal guardians on the importance of education’, he tells OC Media.

Gogadze notes that in cases where the legal guardian was negligent, social workers, within the limits of their duties and responsibilities, may report this negligence, but he did not specify exactly what is done.

He says that they had not received any information about girls being forced to leave education.

Tamar Mosiashvili, an education expert at the Civic Development Institute, a local NGO, says that one of the reasons young girls leave school to start a family is poverty. She says the areas where this is the most common have high levels of poverty.

She also blamed the poor quality of education in regions where ethnic minorities live, citing a lack of teachers and a lack of Georgian language at schools.

Despite this, there are still those who overcome all the difficulties and choose to struggle to continue their education. Gulgun Mammadova, a 20-year-old resident of Tekeli, a village in the Marneuli Municipality, says that she was eager to study as a child, and unlike her two sisters, she managed to save herself from an early marriage.

‘As in the rest of the village, talk of marriage started in our house after we turned 13. Both of my two sisters got married at an early age, but I insisted that I would not marry, but study. I am currently studying at Tbilisi State University’, she says.

Stolen youth

Not every young girl is as lucky as Gulgun. Two young girls from the same school in the village of Karajala, in Telavi Municipality, have committed suicide in recent years, in 2012 and 2014. Both were unhappy about being forced to marry.

The Telavi District Prosecutor’s Office told OC Media that while criminal investigations were launched into both cases, ‘because of a lack of any evidence of wedding preparations’, the parents were not prosecuted.

Those who fall victim to early marriage and are deprived of their youth sometimes themselves justify these traditions.

Sunbul, the grandmother of one of the girls who committed suicide, says that she also got married at 14. She says that despite her unwillingness to create a family at such a young age, she could not protest against this common tradition.

‘I didn’t know anything when they informed me that they had given my consent for the marriage and that my wedding would be in autumn. We had no right to say that we didn’t want to get married, so we didn’t even think about protesting it.’

‘This happened in every family — when a girl turned 13–14, she had to get married. My husband was in charge of his family, which contained 14 people. And I had to take care of all of them. It made my childish health worsen. Now I understand that getting married at an early age is not a good thing. However, it is our tradition. If I don't teach my granddaughter what I know, she would be abducted by someone else. What happens, happens; why look for guilt?!’.

Domestic violence

Domestic violence against ethnic Azerbaijani girls who do not have the right to say a word to their parents about their education or personal happiness often continues in the house of their husbands. When they try to protest, their lives can be in danger.

Twenty-year-old Gunay Isayeva, a resident of the village of Ponichala, was killed in 2016 because she wanted to leave her husband. He cut her throat in front of her two children.

Gunay was abducted by her husband when she was 13. Although he threatened to kill her when she left for her grandmother’s house, her relatives did not call the police or take any precautions.

Gunay’s husband, Novraz Aliyev, was sentenced to 11 years in prison.

Another resident of Ponichala, 26-year-old Zarifa (not her real name), says that since getting married eight years ago, her husband has beaten her almost every day.

‘Recently he hit my head with his fist so badly that I’ve been in pain for days, blood has accumulated in my eyes, and my vision has deteriorated. I’m embarrassed to wear clothes with short sleeves in the summertime because there is no place left on my arms without bruises. But now all my relatives and neighbours know about this, so they don’t ask me when they see bruises on my face or body. My condition has become usual both for me and for them’, says Zarifa.

She says that there are women in the village who have addressed the police about their husbands’ violence, but since there are no serious interventions, this often works against the women.

‘You address the police to get any solution. But they just come and have “preventive conversations” with the husband and then leave. They never send female police officers so that we could explain our problem to her better. Gunay was a victim of this indifference. And perhaps tomorrow I will be the victim…’ says Zarifa.

Relatives of a schoolgirl abducted in Ponichala in February 2017 blocked off the nearby Tbilisi–Rustavi road for several hours protesting that their application to the police had not been accepted for three days.

Tightening laws but what about implementation?

Ana Arganashvili, a spokesperson for local rights group the Partnership for Human Rights, believes that the main barrier to tackling domestic violence in Georgia is that law enforcement agencies are not sensitive to the issue and there is no specific state policy to protect victims from potential risks.

‘In situations involving violence and murder, the state and the police have the same obligation to protect the lives of everyone. Obviously, domestic violence is secretive, and sometimes victims do not complain about it, being afraid of the person who commits the violence, or they may withdraw their complaint’, says Arganashvili.

‘For this reason, the police must show special sensitivity and take all necessary measures to prevent a possible crime. At present, Georgian police treat domestic violence as any other crime and do not apply a sensitive approach.’

Arganashvili notes that after adopting the Istanbul Convention in 2017, a Council of Europe convention on preventing domestic violence, Georgia has committed serious efforts to prosecute abusers.

‘However, there are still major barriers to the prevention of violence against women and in the field of women’s empowerment’, says Arganashvili.

According to the Human Rights Department of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, which was created last year, violence against women and the timely detection of crimes connected with the early marriages of girls are among the main priorities of the agency.

The ministry told OC Media that during the first nine months of 2018, 133 criminal cases were initiated based on suspicion that an adult was ‘co-living with a juvenile’, i.e. in an unregistered marriage with a child.

These cases were initiated under three articles of the criminal code, for ‘sexual contact with minors’, ‘forced marriages’, and ‘unlawful imprisonment’. Of these, 23 were connected with the abduction of minors.

The majority of these cases were reported in the Kvemo Kartli region, including all of the cases of forced marriage.

The ministry says they are planning to train investigators for such crimes, in addition to strengthening communication and cooperation with law enforcement, municipalities, social and educational institutions, and increasing public awareness.

The laws now forbid early marriages in any case

According to the Civil Code of Georgia, the minimum age for marriage is 18. Prior to December 2015, girls aged 16–17 could officially marry with their parents' consent. After an amendment to the law, the marriage of girls aged 16–17 was allowed in the event of pregnancy or the birth of a child.

Following this, a proposal by the Public Defender led to the complete ban of marriage to a girl under the age of 18 beginning January 2017.

However, Ekaterine Skhiladze, an employee of the Public Defender’s Office, says that the amendment to the law has not yielded results, and the issue of early marriage remains a serious problem.

‘Despite a number of positive steps proposed by the Georgian government, early marriages and engagements remain some of the most disturbing manifestations of gender inequality, which adversely affects girls' rights. According to official statistics, in 2017, six cases related to forced marriages, 41 cases of rape, and 173 cases of sexual intercourse with a person under the age of 16 were registered. Early maternity indicators are also high — 835 cases’, Skhiladze says.

Skhiladze, stressing the importance of raising public awareness about the serious consequences of early marriage, also says the problem is exacerbated by the weak connections between education institutions, law enforcement agencies, and the Social Service Agency working with families.

Twenty-six women killed in one year

Dimitri Tskitishvili, a member of the Gender Equality Council in the Parliament of Georgia, notes that despite thousands of women being subjected to physical and psychological violence, many still consider it a private domestic matter.

‘Official statistics on the number of victims are increasing year by year. Domestic violence and violence against women can lead to tragic consequences. In 2017 alone, 26 femicides occurred. The causes of the femicides give us an idea of how society's attitude towards women should change. Traditional gender roles are still strong in Georgian society. These stereotypes, for example, prevent women from entering the dominant areas of men in politics’, says Tskitishvili.

According to him, only 11% of employees in government structures are women, while just 15% of MPs are women.

In the village of Mskhaldidi, Sanubar's mother, Firuza Mammadova, says she regrets that her daughter was forced to marry at an early age.

‘They forced me to get married at an early age. I was 14 years old’, Mammadova says. ‘I wouldn’t wish for my daughter to spend sleepless nights looking after her child like me. But it’s custom not go against the promise of our father. There is no way back. I raised them, and despite not being able to educate them, I hope Sanubar will be stronger than me…’

Sanubar, who is only 17 years old, says she has forbidden herself to dream or desire anything for her future.

‘I have no expectations from my life. I'm frustrated by my own future’ she says. ‘I just want to give my daughter a good education and hope she will be able to build a happy future. My parents took my dreams and my childhood from me. But I will not let my daughter live such a life.’

This article was prepared with the support of EU-funded OPEN Media Hub project.

5 June 2019

5 June 2019