The first U-turn

The statement from the President of Armenian in September 2013 sounded like a bolt from the blue. He would not sign the Association Agreement with the European Union at the planned November Eastern Partnership Summit in Vilnius, he said. Instead, Armenia would be joining the Russian led Eurasian Economic Union (EAEU). This signified Armenia’s departure from a multi-vector foreign policy.

At that point, Armenia had been in talks with the EU for four years. Such a sharp change in the official position of Yerevan created the impression that Russia was certainly involved. Moscow is unhappy about the rapprochement of post-Soviet countries with Europe.

The Armenian authorities justified their decision using economic arguments: the market in the post-Soviet space, and by extension of the EAEU, is well known to Armenians. Therefore, it’s in this market that Armenian goods are competitive. They also claimed that joining the Eurasian Economic Union would lead to an influx of Russian investments into Armenia.

The government also talked about security, which was an odd thing to hear, as the EAEU encompasses just economic and trade cooperation in the post-Soviet space, and is in no way connected to security and defence. In addition, Armenia already has extensive defence cooperation with Russia. It was already a member of the Collective Security Treaty Organization (CSTO), which includes Russia, Kazakhstan, Belarus, Kyrgyzstan, and Tajikistan, and hosts a Russian military base on its territory. Armenia’s accession to the EAEU did nothing to prevent a four-day war around Karabakh in April 2016.

A second U-turn

By October 2015, relations between the EU and Armenia had already experienced a new thaw: the European Commission gave consent to restart talks with Armenia to prepare a new agreement. This time the negotiations were successful.

Some worried that the Armenian government would not risk signing the new agreement. They understood that Russia would be against any agreement between Armenia and the EU. The Kremlin was not keen on losing its geopolitical weight in the region and its privileged position in the Armenian economy.

But the new agreement, the Comprehensive Economic Partnership Agreement (CEPA), was signed by both sides at the Eastern Partnership summit on 24 November 2017. The main reason Armenian authorities made this second U-turn was that they had encountered serious problems because of their one-sided geopolitical position.

The economic crisis

After Armenia’s accession into the Eurasian Economic Union, exports of Armenian products to Russia did not increase. In fact, they significantly decreased. After three years in the union, investments had dropped by around 60%. Moreover, in an attempt to protect their own producers and labour force, Russia has closed itself off to Armenian products and workers in many areas of the economy. For example, Russia has increased excise duties on alcohol, and revoked the validity of Armenian driver’s licenses on Russian roads.

Armenia has also encountered new problems in its trade with Georgia and Iran, the countries with which they have open land borders, because of switching to EAEU standards. Borders with Azerbaijan and Turkey are closed because of the situation in Nagorno-Karabakh.

Now Armenia is hoping that signing CEPA will ensure financial support for projects in the country, and that it will create a better investment climate.

The previous skew towards Russia also led to the strengthening of monopolies within the country. The transfer to Gazprom of the monopoly on gas supplies and distribution in Armenia has created a situation in which Armenians have to pay twice as much for gas as Ukrainians. Prices on Armenian airlines are very high due to their dependence exclusively on Russian airlines.

Against this background, the agreement with the EU provides chances to create alternatives in the energy, aviation, and tourism sectors. In addition, the agreement includes provisions to combat corruption and monopolies, and to support small and medium-sized businesses. This means that a return to a multi-vector policy will directly affect the wellbeing of Armenian citizens.

Foreign policy

Cooperating exclusively with Russia isolates Armenia from the rest of the world. So, Armenia found itself in a marginal minority with Russia during a vote in the Council of Europe on the Crimean situation in 2014. All 43 other members of the Council supported Ukraine.

Diplomatic benefits of Armenia from membership in organisations dominated by Russia are also ambiguous. Membership in the CSTO and joining the EAEU did not rally participants of these organisations around Armenia on the Karabakh issue. During the four-day war in Nagorno-Karabakh, the CSTO did not make a single statement on the situation, and some members took an altogether anti-Armenian stance.

It is no secret that Russia manipulates the Karabakh question, and is offering Azerbaijan help in exchange for joining the EAEU. The ‘Lavrov plan’ envisions Armenia giving up certain territories in Nagorno-Karabakh to Azerbaijan.

It’s therefore evident that the presence of many international actors in the South Caucasus is in the interests of Armenia. The presence of such players as the EU and the US will help prevent a complete Russian monopoly on power in the region.

Although, on an official level the Kremlin says that Armenia has a sovereign right to build its own relations with the EU, its response is quite expected in light of sanctions and economic difficulties that prevent Russia from helping Armenia economically.

This does not mean Russia is not unhappy. Moscow’s irritation is reflected in the information climate on Russian television. On the evening of 24 November, after the signing of CEPA, this event became one of the key talking points on the programme ‘Time will Tell’ on Russia’s main channel — the First Channel — where Armenians were called traitors. Another programme, on ‘Meeting Point’ on NTV, compared Armenia on 29 November to a ‘philandering wife of Russia’.

Bridge between East and West

A multi-vector policy will allow Armenia to make the most of its geographic potential. Cooperation with the West could turn Armenia into a bridge between the EU and Russia, since it’s the first country of the Eurasian Economic Union to sign an agreement with the EU. In a sense, Armenia might become an example of cooperation in the two competing systems.

If Armenia acts promptly, the country could provide transit for cargo going from East to West and vice versa. The Chinese grand project titled the ‘New Silk Road’ might pass through Iran and Armenia, which could become a real platform for regional cooperation.

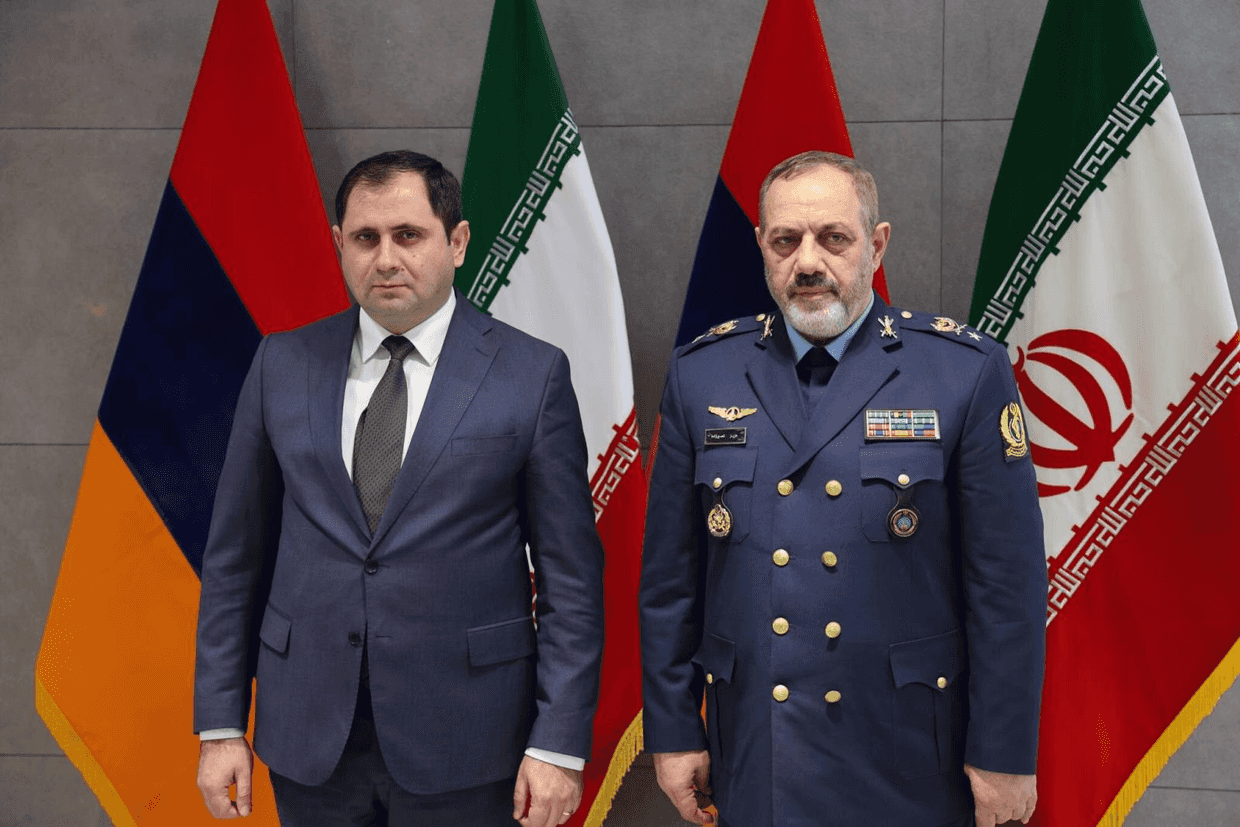

In the region, Armenia could also serve as a bridge of cooperation between the EU and Iran in a number of important spheres including energy, atomic energy, transport, banking, governance, and shipping. Armenia already has experience working with Iranian authorities and companies. In its turn, Iran is also interested in dealing with the EU through Armenia, since it has difficulties in its relations with countries in Europe.

Thus, the transition back to a multi-vector policy will help diversify Armenia’s foreign policy and economic ties and correct the consequences of its one-sided cooperation with Moscow.