From tropes about rich, greedy merchants, jokes about cultural appropriation, to overblown fears of separatism, Georgia’s ethnic Armenian community are frequently the targets of hate.

‘My mother is Armenian, and I will always speak proudly about it’, Georgian Prime Minister Zurab Zhvania said in Parliament in June 2004, after an MP suggested that ‘some people’ hid their parents’ ethnicity.

Being ‘secretly Armenian’ has been a common accusation between political rivals in Georgia, with targets including former President Mikheil Saakashvili and former Parliamentary Speaker Nino Burjanadze.

‘They always said about Zurab Zhvania — “he’s an Armenian, he’s an Armenian!” — but I liked the way he replied’, 68-year-old Roza Gharibyan tells OC Media. Roza was born in Tbilisi to survivors of the Armenian Genocide; she now works as a vendor in the city’s Lilo Market.

‘Saakashvili was not Armenian. He was “Georgian” when people liked him and when he became bad, then he became “Armenian” ’, Roza says with a smile.

Gharibiyan has a hard time naming any ethnic Armenians in the Georgian government or parliament, although there are some MPs. ‘No one at all’.

Years after Zhvania’s fiery reply, anti-Armenian speech has largely given way to other forms of xenophobia, mostly targeting migrants from Middle Eastern countries. However, anti-Armenian discourse in the Georgian media is still rampant — especially in its ultra-conservative segment but sometimes also coming from less expected places.

‘Now, I’m waiting for the conclusions of Armenian scholars. I’m sure they will discover that their DNA is, of course, stronger than that of Georgians and it just destroys coronavirus,’, Giorgi Gabunia, an anchor on TV channel Mtavari Arkhi joked on air on 5 April. The channel bills itself as a liberal and pro-Western outlet.

‘The Georgian version of anti-Semitism’

Georgian philosopher Giorgi Maisuradze has postulated that Aremnophoia is the oldest and most widespread form of xenophobia in Georgia. ‘Armenophobia is the Georgian version of anti-Semitism, which engulfs all layers of society.’

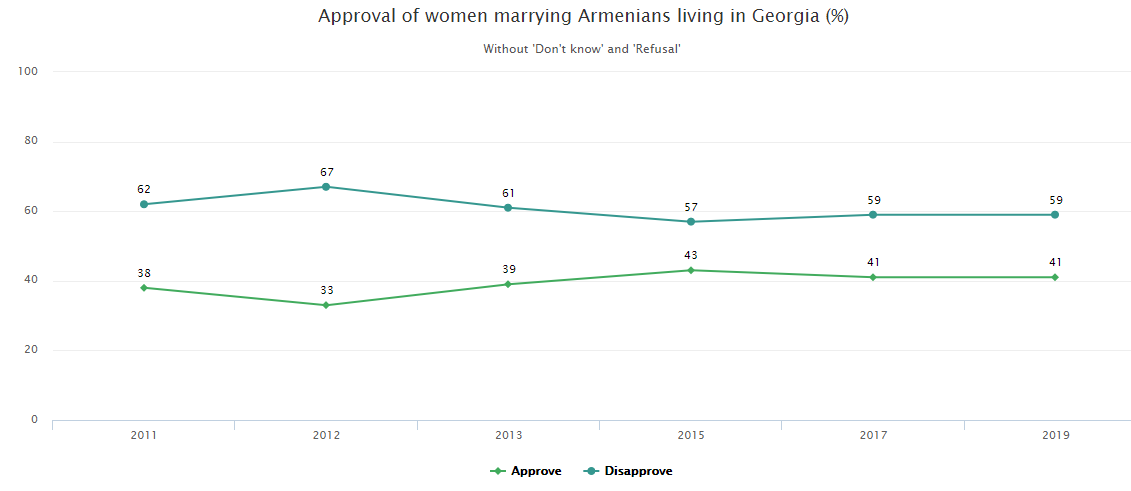

According to a 2019 survey by CRRC Georgia, 59% of Georgians who gave a definitive answer disapproved of Georgian women marrying an Armenian living in Georgia while only 41% approved.

Also, 72% disapproved of Georgians doing business with Armenians living in Georgia, against 28% approving.

Over the years, many stereotypes have formed about Armenians.

Defending gentrification plans for Sololaki, a historical district of the capital known for its multi-ethnic character in 2007, Georgian MP Beso Jugheli argued that ‘Mikirtuma doesn’t always have to live in Sololaki’.

The image Jugheli invoked was that of Mikirtum Gasparich Trdatov, the character of a gluttonous, calculating, and greedy Armenian merchant in the 19th-century Georgian play ‘Separation’. Mikirtum was also included in late Soviet Georgian historical film Khareba and Gogia.

Jugeli’s Armenophobic comment, and indeed the play itself, echoed the mood of disgruntled and impoverished Georgian aristocrats who had a hard time competing with a financially secure Armenian middle class in 19th century Tbilisi. At least, that’s where some scholars see the roots of modern Armenophobia in Georgia.

According to one line of argument, Georgia’s modern national identity is deeply embedded in highlighting differences from Armenians — the ‘narcissism of small differences’, as some have characterised the tendency in intimate inter-ethnic dynamics.

Mikirtum remains among a number of racially stereotypical images of an urban Armenian in Georgia.

‘Go back to your Armenia!’

The war between Armenia and Azerbaijan brought some of these sentiments once again to the fore.

‘I felt a lot of hate in this period due to my Armenian ethnicity’, says Rima Marangozyan, a fourth-year journalism student at Tbilisi State University.

Rima was raised in the city of Akhalkalaki, in southern Georgia, which has a large Armenian population.

‘[This is] something I had never experienced in Georgia. It’s hard, quite frankly, to go back to a life where I was rather a citizen of Georgia than a representative of an ethnic minority living in Georgia’, she says.

Despite Georgia insisting on its neutrality since the early years of conflict, many ethnic Armenians both in the region and in the diaspora accused the authorities in Tbilisi of allowing Turkish arms to transit through Georgia to Azerbaijan.

Rima says that Armenians berating Georgia for this online had caused a backlash and made Georgians also vulnerable to disinformation encouraging anti-Armenian sentiments.

‘I was personally told by someone on Facebook: “You Armenian! Go back to your Armenia!” ’, she recalls.

Rima says that what lies behind Armenophobia in Georgia was that ‘the Georgian nation does not know the Armenian community’. She said Georgians often have preconceived perceptions about Armenians, frequently formed under the influence of the media.

She said the TV media frequently presented things out of context, citing Armenians’ use of ‘Javakhk’, merely the Armenian language name for the Javakheti Region where many ethnic Armenians live, as some kind of territorial claim.

She also accused the Georgian media of bias during the war, covering mostly crimes committed by the Armenian side instead of both.

‘We depend on the media, especially on social media, and Georgian people have become the victims of manipulations and disinformation’.

‘Becoming Georgian advances you in life’

Roza Gharibyan received her education, and learnt about what her family fled from, in an Armenian school in Avlabari, or Havlabar, a historically Armenian District of Tbilisi.

She was initially hesitant to recount her personal recollections, but as we spoke, Roza opened up more.

She recalled she and other Armenians being called ‘lousy Armenians’ and ‘infested with lice’ in public transport, and her boss in a sweatshop she worked at once saying that ‘Armenians should work, Georgians should have fun’.

Roza also remembered refusing to go to a hospital as her labour approached, saying she was terrified.

‘When they started calling us “guests”, during [the tenure of first Georgian President Zviad] Gamsakhurdia, I really thought they would kill me [in a hospital]’, she says.

‘But when I went, I got such nice treatment I could not believe it. I was in fear because of talks about “other nations” in those years, the 1990s.’

She also recalled her cousin, who married an ethnic Georgian in Sachkhere, western Georgia, overhearing a woman telling a child: ‘sleep or an Armenian will come and kill you!’ She said her cousin was shocked.

Later, Roza moved to Tbilisi’s Varketili District, where the Soviet authorities of the time were settling those whose houses they had demolished in Avlabari in 1986.

‘All my neighbours who were Armenians became Georgians, during [the presidency of Mikheil Saakashvili 2004–2013]. It advances you in life, otherwise, you can’t move forward’, she says.

She also insisted the situation had ‘got better lately’.

Both her children were schooled in Russian, fluent in Georgian, and also speak Armenian at home. Her grandchildren, she says, ‘will probably be educated in Georgian’.

Georgian victimhood

Besides allegations of separatism, other Armenophobic tropes in Georgia include that Armenians claim aspects of Georgian culture as their own and have a wealthy international lobby in the West with unlimited influence against the unassuming Georgians.

‘I'm not Armeniaphobic [sic] but this violates any logic. This is a typical example of what kind of predators they are’, Shmagi Khubuluri, Director of the Gori City Hall Youth Centre complained on 24 September sharing a video on Facebook that attributed churchkhela, traditional candy with nuts, to Armenian culture.

In Armenia, the food is commonly known as sujuk. Variations of the food are common across several cultures.

Giorgi Khasaia and Artur Petrosyan performing ‘Lavash nash!’ (Lavash is ours!), which portrays the ‘infantile resentment between Georgia and Armenia’.

These narratives are also popular among conservative Georgian Christian clergy, as the Church remains one of the strongest hotbeds of Georgian ethnic nationalism.

‘Armenians claim everything Georgian’, said Georgian Orthodox Christian deacon Davit Kvlividze in a June 2018 sermon to his parish.

‘They are smart. They've settled with Russians, they have settled with the Americans too, they have Armenians in the [US] Congress, they’ve settled in France too, and we, the fools, have cut ties with everyone’, he continued.

The Orthodox Church did not limit its anti-Armenian efforts to preaching. In recent years, Georgian-Armenian relations have been marred by disputes over Orthodox Churches in Georgia.

In 2017, Georgian authorities handed over the Tandoyants Saint Astvatsatsin (Saint Mary) Church, a dilapidated Armenian site, to the Georgian Orthodox Church, mirroring its Soviet expropriation from the Armenian Orthodox Christian community in 1924.

The Diocese of the Armenian Apostolic Church has been unsuccessful in their efforts to stop the construction of a new Georgian Orthodox church on the base of the building.

According to Tbilisi-based rights groups the Human Rights Education and Monitoring Center and Tolerance and Diversity Institute, this was a ‘clear example of loyalty towards the dominant church and the discrimination of Armenian Orthodox community’.

‘If they get to you, expect worse’

Some members of the Armenian community in Georgia tend to avoid words like ‘Armenophobia’ and ‘hate’, like Karina Grigoryan, a former state security official who was raised in the Aspindza District of southern Georgia's Samtskhe–Javakheti Region.

In conversation with OC Media, Karina nevertheless admitted that the country was ‘not without its problems, especially highlighted during the last military conflict between Armenia and Azerbaijan’.

Karina abstained from elaborating further, saying that emotions were still high.

Going back to her school years, she said she, like others, experienced bullying in schools with children chasing after her calling her ‘Armenian’ as an insult.

Karina said that in the 1990s, she was also told to ‘return to her homeland’. She said the number of ‘people like this’ has recently declined.

She says some relatives had told her that studying, or aiming for success, was pointless in Georgia, because of their ethnicity. Other relatives, she says, only inspired her.

‘I had role models like my parents, cousins, also my grandfather — they all had a higher education and their ethnic background did not hold them back in life’.

In January 2013, President Mikheil Saakashvili awarded Karina with a medal of honour for retiring as a police captain at the Interior Ministry in protest at a controversial amnesty law under the new incoming government.

In that polarised society, which was experiencing its first peaceful transition of power, both the amnesty and the award became controversial.

However, having previously witnessed President Saakashvili being attacked for being ‘secretly Armenian’, Karina says she was surprised that ‘even critics of the award called on their supporters not to touch my ethnicity’.

She said it was a sign of times changing.

‘Let me sum up my whole personal experience: It depends on personality. If they notice they get to you with this, expect worse. But if they notice you can’t be hurt by this, they just disappear from your life.’

10 December 2020

10 December 2020