Since the Russian invasion of Ukraine in late February, thousands of Russians have fled political repression, economic troubles, and the possibility of being drafted. In neighbouring Georgia, the influx has been met less than enthusiastically.

‘Right after you pass through the tunnel [on the Georgian–Russian border], you begin to understand that you have left some kind of dystopia and entered a civilised country’, says Aleksandr Belinskiy.

The 35-year-old masseur and car consultant arrived in Georgia in mid-March.

‘You relax; you understand that you won’t be jailed for some post on Instagram’, Belinskiy told OC Media.

‘At least I can speak here.’

Belinskiy expressed a strong objection to Russia’s war against Ukraine, and said that following the war and Russia’s political climate was ‘a matter of security’ for him.

He said that he and his friends had heard about Russophobia in Georgia and expected ‘to be scorned, that there would be aggressive reactions to speaking in Russian’. But, he said that everyone he had met was ‘very friendly’.

A less than warm welcome

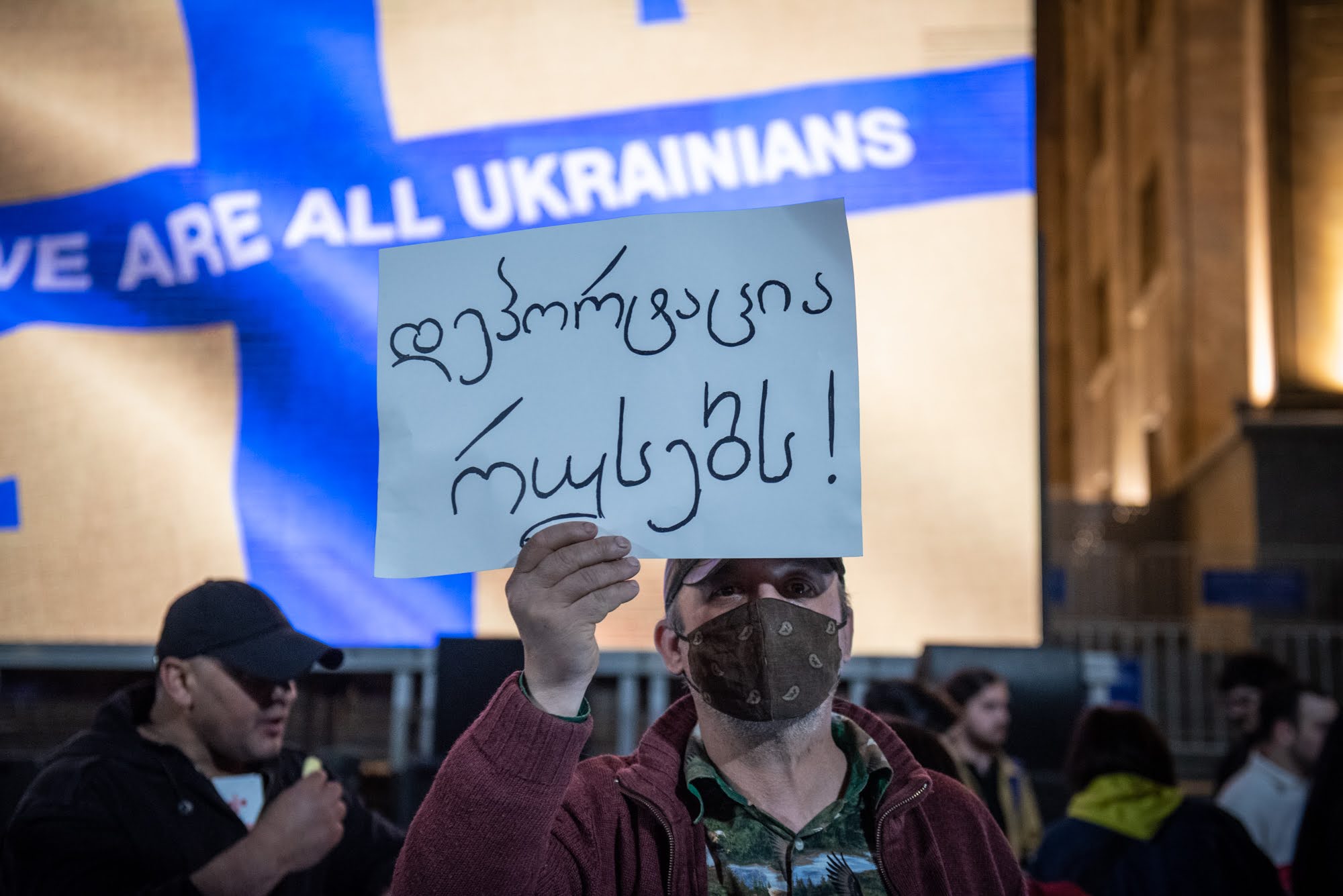

But the welcome for many Russians moving to Georgia has been less warm. On 11 April, Russian émigrés in downtown Batumi were bombarded with a flurry of insults by activists equipped with megaphones.

‘Putin Khuilo [Putin is a dickhead]! Russia is an occupier! 20% of the country you are currently in is occupied. We are not happy to see you here […] We don’t trust you. We can’t be certain that your government won’t invade Georgia to protect you’, were among the many indictments the tourists heard.

Video: courtesy of Lenura Melgazieva.

Similar sentiments have been expressed by some in Geogia’s opposition, including the European Georgia party, whose member Giorgi Kandelaki publicised ‘arrogant’ and ‘anti-Georgian’ messages by some Russians seeking to move to Georgia on social media.

Some members of Georgia’s largest opposition party, the United National Movement (UNM), have also been vocal about the arrival of Russians. In March, MP Nona Mamulashvili vowed to ‘do everything to make Russian citizens that moved [to Georgia] en masse uncomfortable’.

‘No one waits for them here. We call these so-called “Russian tourists” saboteurs’, Mamulashvili told Ukraine’s Channel 24.

According to data obtained from the Interior Ministry, 35,028 Russian citizens entered Georgia between 24 February and 20 March, around 8,000 more than in January. It is unclear how many are remaining in Georgia for the long-term, but the numbers are widely suspected to be higher than previously.

While the ‘influx’ may have been overblown, its anticipation was immediately felt, especially in the capital city of Tbilisi, where rental prices quickly spiked.

Additionally, the Georgian Public Registry received more applications from Russian nationals seeking to register their businesses than in previous years.

According to OK Russia, a Russian NGO aiming to help evacuate Russians who oppose the invasion of Ukraine, Georgia, Turkey, and Armenia topped the list of countries that Russians departed to immediately after the war.

‘Supporters of war’

Efforts to confront Russians in Georgia have often focused on educating them on the crimes of the Russian state abroad.

Those critical of the arrival of Russians in Georgia have frequently accused émigrés of supporting the Kremlin’s military invasion of its western neighbour, or of being ignorant or indifferent to it.

In this vein, libertarian party Girchi chose to greet ‘guests from “occupant [sic] Russia” with ‘awareness-raising’ banners on the Vladikavkaz–Tbilisi highway.

Earlier in March, a group of Georgians also baited Russians seeking accommodations in Georgia using posters on the street promising information on consumer services and discounts. The QR codes included in the signs redirected users to YouTube videos showing scenes of the war and Ukrainian victims, with captions such as ‘not just Putin’s fault’ and ‘protest against Russian aggression!’

Weaponised citizenship

There is also a widely expressed view, including among the activists targetting Russians in Batumi, that the presence of more Russian citizens in Georgia poses an existential security risk.

They cite the Kremlin’s ‘near abroad’ policy of claiming the need to protect the rights of Russian citizens and Russian speakers residing in bordering countries, including in Georgia and in Ukraine and the Baltic states.

‘We do not want so many Russian people to live in Georgia because Putin can one day say that he must defend his citizens and bomb our country!!!’, wrote one of the nearly 16,000 signatories of an online petition demanding the introduction of a visa regime with Russia.

Government critics have argued that the relatively easy access to Georgia afforded to Russians, and allowing them to stay in Georgia for at least a year with no visa, are inextricably connected to the absence of Georgian sanctions against Russia.

They also believe that Georgia is running the risk of becoming a ‘black hole’ for those seeking to avoid international sanctions.

A recent survey by CRRC Georgia suggested that 59% of Georgians supported restrictions on Russians entering the country. Support was especially high among young and opposition-minded people.

Banks and businesses

Neither has the backlash been restricted to public protests and politicians. Several Georgian businesses or small business owners have also jumped on the bandwagon of anti-Russian sentiments, including the country’s two biggest banks.

Georgian–ethnic Russians, Tbilisi-based anti-Kremlin Russian activists, and even Georgians assumed to look like Russians, have all reportedly faced hostility in Georgia.

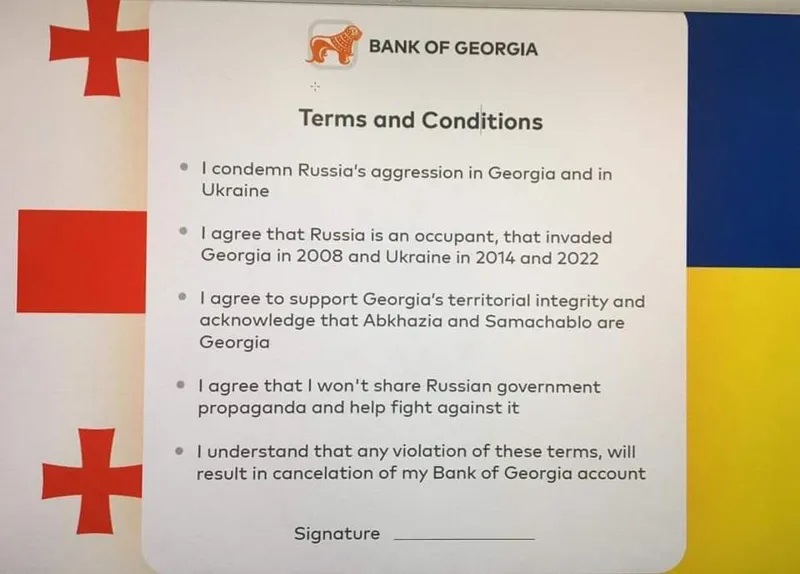

Following the invasion of Ukraine, at least one branch of Bank of Georgia mandated that Russian citizens seeking to open accounts sign forms indicating that they recognise Russia as ‘an aggressor’ and an ‘occupant’ of both Georgia and Ukraine. The forms further obliged Russian clients to ‘fight Russian propaganda’.

Multiple sources, including an opposition Belarusian blogger in their 20s who asked to stay anonymous, told OC Media in March that TBC, another major Georgian bank, was refusing to open accounts for them and other Russian citizens they knew, explaining that they did not want to ‘help Russian citizens evade sanctions’.

Dmitry, a 28-year-old Russian IT specialist, further corroborated the story to OC Media.

‘Putin is not the whole of Russia. We are against everything happening in Russia’, Dmitry told OC Media, while insisting that Georgians he had met ‘were wonderful’ and eager to help him and others.

TBC has not replied to OC Media’s repeated appeal to comment on the issue.

Nikolay Levshits, a Tbilisi-based Russian activist who co-organised the anti-war rally in Tbilisi within minutes of Russia’s announcement of its ‘special operation’, said he had received reports of Russians and Belarusians being refused service by taxi drivers and cafes, or even refused flats due to their nationality.

Levshits is a Research Fellow at the US-funded pro-democracy organisation the Free Russia Foundation.

‘The aggressor is the Russian regime, and not all Russian-speaking people living in other countries, and especially not in Georgia’, Levshits said in an appeal to Georgians on 1 March.

‘Believe me, many of us are now horrified by what is happening in Ukraine.’

OK Russia, which claimed to have interviewed 1,500 Russian émigrés by the end of March, said that 50% of those leaving Russia had faced ‘political pressure’ before leaving their country.

An ‘island of freedom’?

The initial backlash and broad approach to Russians coming to Georgia have helped the Kremlin to allege the existence of Russophobia in the country. It may have also helped the Georgian Government avoid backlash for denying entry to Kremlin critics.

In early March, Economy Minister Levan Davitashvili touted Georgia as an ‘island of freedom’ for those fleeing repressive regimes.

But not everyone would agree with Davitashvili, especially those independent Russian journalists and government critics who have been denied entry.

David Frenkel, a prominent reporter for Russian digital outlet Mediazona was denied entry on 10 March, four days after Russian authorities entirely blocked Mediazona for refusing to censor news on the invasion of Ukraine.

Frenkel was unconvinced with Georgian Interior Minister Vakhtang Gomelauri’s claim that the refusals for potentially sensitive arrivals were not decided from the top, claiming border police had been on the phone for 14 hours awaiting a decision about their entry from superiors.

Another prominent journalist, Mikhail Fishman, an anchor on the independent Russian TV channel Dozhd, cited a similar experience on 5 March.

Dozhd stopped broadcasting soon after Putin signed a law imposing prison sentences of up to 15 years against those spreading ‘fake’ information about Russia’s armed forces.

Fishman told OC Media he had received no reason or clarification on why he was denied entry into Georgia.

‘I understand that I was not permitted into the country because of who I am and what I do. This is totally clear to me’, he said.

Fishman added that he did not plan to attempt to enter Georgia again.

Indeed, Georgia has a track record of not letting in Russian government critics, citing vague reasons as with Fishman and Frankel.

The authorities also have extradited the majority of individuals that Russia had requested. According to the Tbilisi-based watchdog the Social Justice Centre, between 2013 and 2019, Georgia extradited 14 out of 23 Russian nationals upon Russia’s request, including those claiming that they could face persecution, torture, and inhumane treatment in their home country.

But for many of those Russians who have made it to Georgia, the country nonetheless represents a haven.

Aleksandr Belinskiy recalls the first time he witnessed a crackdown on dissent in his native Novosibirsk in 2009–2010, when police moved against residents protesting a ban on importing foreign cars, a significant source of their income at the time.

‘I teared up witnessing this police conduct that was inhumane and violent’, he says.

Belisnkiy said the authorities had instilled a fear of speaking out among Russians ‘on an almost genetic level’.

‘Every family has relatives who were detained, executed, or banished since the Russian Revolution’.

‘The worst thing is that you get used to it; it’s like a hair that grows on your head, it happens slowly, and you don’t notice it.’

He said that by 2014 it was ‘all too clear’ for him that the political climate in Russia ‘would only get worse’.

Belinskiy told OC Media he was not planning to return to Russia.

‘They have simply destroyed my homeland.’

15 April 2022

15 April 2022