During the latest Armenia–Azerbaijan war, Russia deviated from its long-term alliance with Armenia, reneging on its formal commitments and instead offering inaction and equivocation. Its weak response takes place against a backdrop of military disaster and shifting interests.

In the early hours of 13 September, Azerbaijan launched its largest attack on Armenia since the end of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War.

Hours after hostilities broke out, Armenia’s Security Council held an extraordinary session, and made the decision to apply to both the Collective Security Treaty Organisation (CSTO) and Russia for assistance, the latter based on a Treaty of Friendship, Cooperation, and Mutual Assistance signed in 1997.

The CSTO, whose treaty states that an attack on one member will be considered an attack on all, responded by holding an emergency meeting to discuss the escalation. Rather than providing military support, as stipulated in the treaty, the organisation decided that a ‘fact-finding mission’ headed by the CSTO’s secretary general, Stanislav Zas, would be dispatched to Armenia to assess the situation.

This response meant that the CSTO once again chose performative gestures over real action. Neither before the arrival of the mission to Armenia, nor after its departure, did the CSTO call Baku out for its unprecedented attack.

Russia also made it clear from the beginning that it would not take sides in this new escalation.

All official statements coming from Moscow have been kept neutral, despite evidence and consensus that, on this occasion, Armenia’s sovereign territory had been attacked by Azerbaijan. In its first statement following the outbreak of hostilities, the Russian foreign ministry focused on the need to delimit and demarcate the Armenian-Azerbaijani border, despite the fact that towns well within the sovereign territory of Armenia had been shelled by Azerbaijani forces.

Even Azerbaijani shelling of a Russian border guard facility in Armenia’s Gegharkunik Province failed to shift Moscow’s rhetoric.

In the end, Armenia received no actual assistance from its alleged allies.

The towns of Goris, Kapan, Jermuk, and Vardenis, in Armenia’s southern and eastern provinces, were heavily shelled for two days, and Azerbaijani armed forces occupied a swathe of Armenian territory. More than 200 Armenian servicemembers and civilians were killed or remain missing.

A ceasefire was reached 44 hours after it broke out — reportedly through US mediation. Russia’s voice remained a notable absence from the dialogue.

Why was Russia not involved?

There are a few obvious reasons for Russia and the CSTO’s inaction in the face of the deadliest escalation since the end of the Second Karabakh War; most notably, its decreasing military capacity and shifting interests in the region.

The war in Ukraine has been the Kremlin’s number one priority since it began, and the recent Azerbaijani attack against Armenia took place at almost the same time as a significant Russian military loss on the Kharkiv front.

Tied up in Ukraine, Russia has no intention of taking sides in the Armenia–Azerbaijan conflict or getting involved in any sort of confrontation with Baku, let alone Ankara.

And Moscow’s military failures in Ukraine appear to have emboldened the Aliyev regime. Knowing that Armenia’s main ally has its focus and military might elsewhere, Azerbaijan has used the power vacuum in the South Caucasus to test the red lines of both Russia and the international community.

Russia has also become increasingly dependent on both Turkey and Azerbaijan as it attempts to mitigate the consequences of Western sanctions; Ankara is a key trading partner for Moscow and has been vital to keeping Russia’s economy afloat.

In early August, Russian President Vladimir Putin and his Turkish counterpart Recep Tayyip Erdoğan met and agreed to grow foreign trade between the two countries to $100 billion by 2030. At a meeting between the leaders on 16 September, Putin announced that Turkey had also agreed to pay for 25% of its Russian gas imports in roubles.

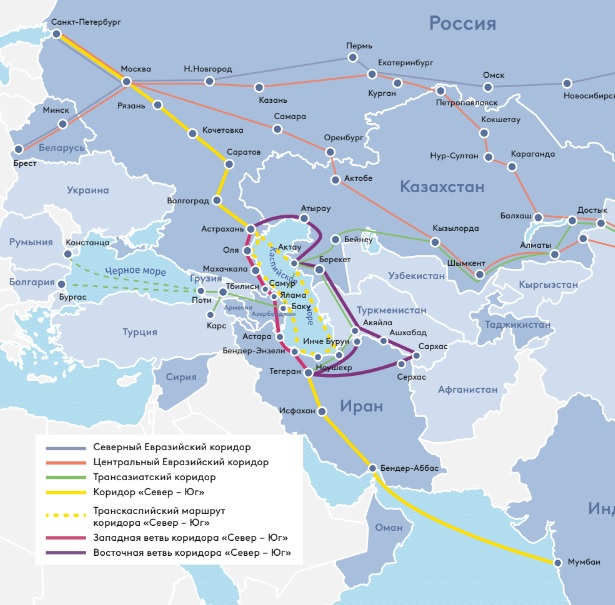

Days before the outbreak of hostilities, Russia, Azerbaijan, and Iran signed a declaration in Baku on the development of a ‘North-South’ international transport corridor. This corridor, which would stretch from Saint Petersburg to Mumbai via Baku and Tehran, became vitally more important for Moscow after its invasion of Ukraine, and the sanctions that followed. Russia aims to make up for its loss of access to European markets by branching into Asia, and relies on Azerbaijan’s cooperation for this to take place.

Russia’s interests have also shifted as it pushes deeper changes in the region, particularly reestablishing transport links between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

This process was agreed upon in the trilateral statement signed by Russia, Armenia, and Azerbaijan that brought an end to the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War in November 2020.

But in the years and months since, the sides have been unable to agree on how the normalisation of transport would actually be implemented.

Yerevan has repeatedly expressed an interest in reestablishing all transport links that existed during the Soviet Union, but stresses that this process should be implemented with respect towards the sovereignty and national legislations of the countries involved, as well as in accordance with international norms.

Meanwhile, Baku wants a corridor through southern Armenia that would connect mainland Azerbaijan with its exclave of Nakhichevan and would be controlled by the Russian Federal Security Service (FSB). Yerevan has declared on multiple occasions that the creation of an extraterritorial corridor on Armenia’s territory is out of the question.

Russia is interested in opening the corridor because it wants a safe land connection with Turkey through the territory of Azerbaijan and Armenia. De facto control of the corridor would also increase Moscow’s leverage in both Baku and Yerevan.

Russia’s relative weakness and growing dependence on the Turkish-Azerbaijani tandem, as well as its desire to preserve its role as an impartial broker in the Armenian–Azerbaijani context are the primary reasons for the Kremlin’s inaction during the latest escalation.

As Moscow is the primary decision-maker in the CSTO, the organisation did as it usually does, and fell into line with the Kremlin’s plan of action.

What does this mean for Armenia?

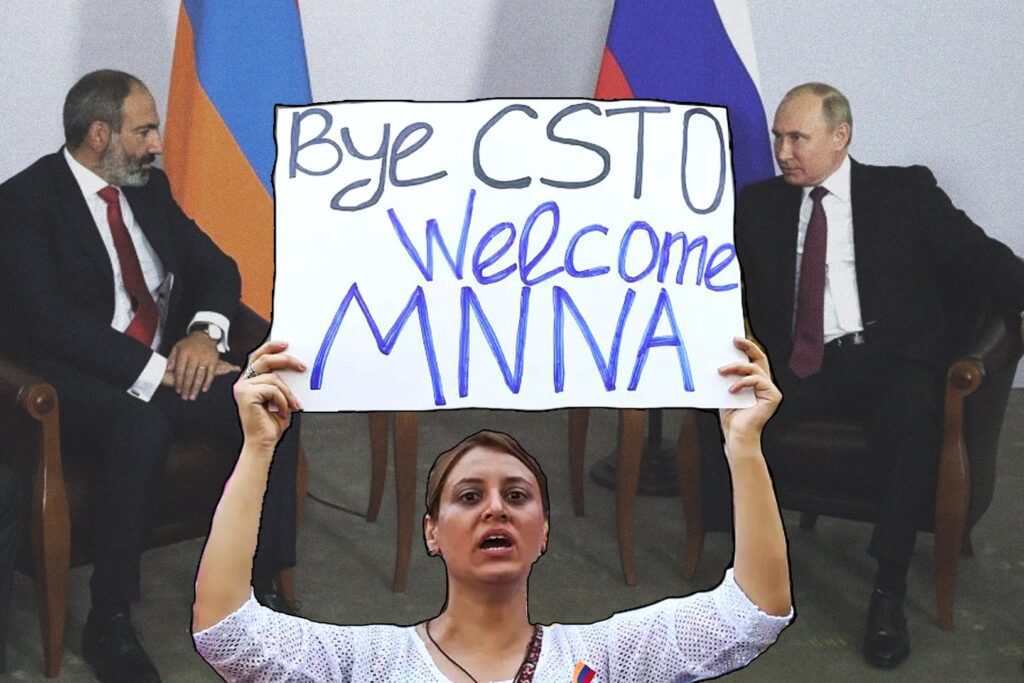

Russia and the CSTO’s passive behaviour during the latest escalation sparked outrage in Armenia, driving the country’s leaders and population to question the country’s membership of the CSTO and its formal alliance with Moscow.

Several pro-Western political parties have organised rallies in Yerevan, demanding that Armenia leave the CSTO, while senior Armenian officials including Speaker of the National Assembly Alen Simonyan and Secretary of the Security Council Armen Grigoryan have publicly expressed their disillusionment with Russia and the CSTO’s conduct.

Even Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan hinted at Yerevan’s dissatisfaction with Russia and the CSTO during his speech at the 77th session of the UN General Assembly. Armenia also sent a clear message about its discontent by refusing to participate in exercises of the Collective Rapid Reaction Forces of the CSTO that were held in Kazakhstan from 26 September–8 October.

[Read more on OC Media: Opinion | Armenia’s old allies have failed it, new ones have yet to appear]

These developments are a huge blow to Russia’s standing in Armenia. At this point, even pro-Russian actors in Armenia have begun to realise that Moscow is not capable of fulfilling its obligations towards Yerevan.

It’s become clear to almost everyone in Armenia that the Russian deterrent isn’t working, and that the CSTO has once again been proven to be an absolutely dysfunctional alliance.

Armenia was a founding member of the organisation and always saw it not only as a framework for interaction with Moscow, but also as a practical military arrangement — CSTO membership was supposed to guarantee Yerevan Russian weapons at favourable prices.

But Russia has reneged on that too, as the country is not just unable to sell weaponry and armaments because of the war in Ukraine, but may also have failed to fulfil existing contracts.

Nonetheless, it is highly unlikely that Armenia’s leadership will initiate a process of withdrawal from the CSTO or drastically change its foreign policy direction in the near future.

Azerbaijan’s tactics of coercive diplomacy and continuous aggression against Armenia have put Yerevan in a very precarious position.

Armenia doesn’t have the luxury of being able to anger or further alienate Russia in the face of renewed conflict with Azerbaijan, and any attempt to leave the Russia-led defensive alliance would likely cause retaliation from Moscow.

Russia has a significant military presence on the ground in Armenia and Russian peacekeepers play a key role in preserving the fragile peace in Nagorno-Karabakh.

These are factors, which cannot be ignored by decision-makers in Yerevan, make it likely that Armenia will remain a formal Russian ally and a member of the CSTO for the foreseeable future.

However, Russia’s relative weakness and inability to deter Azerbaijan will also be taken into account. In this new context, Yerevan has more room for manoeuvre in its foreign policy and security alliances — something it is already making active use of.

Following the most recent outbreak of war, the number of meetings between Armenian senior officials and their Western counterparts was a clear indicator of Yerevan’s new Westward leanings. While Armenia may not be looking to leave Russia’s fold in the immediate future, the country’s inaction has begun a process of diversification in Armenia’s foreign policy. It remains to be seen how this will take shape in the months and years to come.

10 October 2022

10 October 2022