Dying on the steps of parliament — Georgia’s Shukrutians make last bid for their homes

After over a month on hunger strike, mostly on the steps of Georgia’s parliament, residents of the village of Shukruti are facing declining health and plummeting temperatures, with little hope of saving their village from destruction.

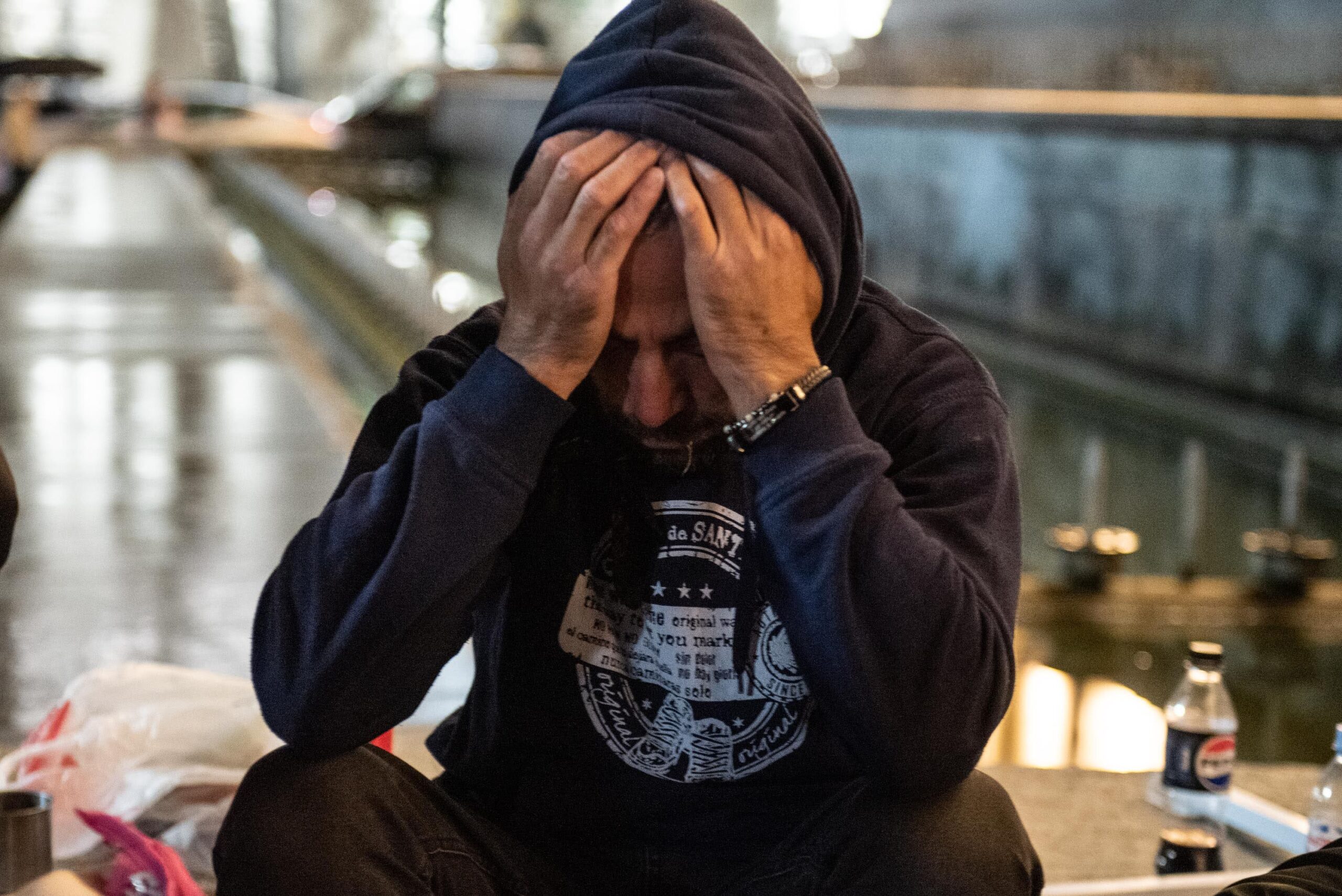

‘I don’t think I’ll witness my child growing up. I don’t have much energy left in me, maybe a few days? I don’t know’, says Giorgi Bitsadze, 33.

Bitsadze has always been the funny one, cracking endless jokes to friends, family, and anyone he happens to meet. But in the past days, those jokes have dried up, replaced by a grim determination to see his village’s fight through to the end.

He says he has lost more than 15 kilogrammes since he and five other people from the village began their hunger strike to demand adequate compensation from the mining company which they claim is causing their village to collapse.

‘I am just bones and skin now, but I am not planning to give up, I will not return [to my village] defeated.’

The six Shukruti residents have been on hunger strike since 1 September, with some sewing their mouths shut that day. They have been camped alongside other Shukrutians on the stairs of parliament in Tbilisi since 11 September; a last resort after direct protests at the entrance to the mines were banned and protesters fined.

With their rapidly deteriorating physical conditions receiving little to no attention from politicians, and blunt dismissal from the mining company, a number of protesters have begun to refuse even sugar, accelerating their physical decline.

‘We were swimming in water, it was terrible’, says Giorgi, adding that their sheets and blankets had been soaked.

Sleeping under a haphazard assembly of umbrellas and makeshift tarpaulins after police banned them from erecting any kind of protective structure, the protesters have remained resolute in the face of storms and heavy rains

Giorgi, a former mine employee, tells OC Media that he used to have his own house, which completely collapsed. For that house, the company gave him ₾20,000 ($7,300) in compensation, a sum which he says barely approached the real value of the house, let alone the costs of finding or building a new one.

Giorgi and his family were unable to find new accommodation, so moved in with his mother, and it is his mother’s house that he is now fighting to save. Giorgi and four other protesters who had worked in the mines were fired after joining the protest.

‘I have no job, no income, no house. We have to fight this injustice and I personally am ready to sacrifice myself in this fight’, says Giorgi.

Amiran, another protester on hunger strike, was the first to refuse anything but water. Increasingly weak, he mostly lies on the steps of parliament unless he has to go to the bathroom, which is in 9 April park, around 6-7 minutes’ walk from the parliament. The hunger strikers struggle to reach the facilities, and go in groups to help each other and ensure they don’t collapse.

Amiran says that since beginning his hunger strike, his vision has deteriorated so much that he now uses a cane to walk.

This is the second time that Amiran has sewn his lips shut in protest against damage to his village. The first mass hunger strike, in 2021, ended after the mining company signed individual agreements with hunger strikes; agreements that the protesters claim the company failed to fulfil. He adds that while his house is collapsing, this is not the main reason driving his protest.

‘The most important thing for me is my parents’ grave. Five metres from their graves, the soil collapsed. Soon their tombs will fall from there. I can’t watch it, I can’t let it happen’, he says.

An escalating protest

In recent weeks, colder weather conditions have made it harder still for those protesting outside parliament.

In the first week of October, around a dozen women from Shukruti committed to spending their nights outside parliament with the hunger-striking men, with some women beginning a hunger strike too. Previously, the women would spend their nights at the homes of friends or relatives in Tbilisi before returning in the morning.

But after setting up inflatable mattresses alongside the protesting men on 30 September, police demanded they remove them, threatening to arrest the women and ‘use force’.

As the confrontation was growing, Giorgi lost consciousness and was taken to hospital by paramedics, who described his glucose levels and blood pressure as ‘alarming’. Facing a crisis and protesters in floods of tears, the police appeared to back off.

But any suspicions of sympathy were short-lived, with protesters noting that the police have only become tougher.

Vato Siprashvili, an activist from Tbilisi, told OC Media that he brought a few blankets and sleeping bags for the protesters, but the police searched his bags and allowed him to hand over only the blankets. Other groups of people reported the same on attempting to bring blankets and sleeping bags.

Natia, the daughter of one of the protesters, adds that she had to negotiate with the police for hours in order to get permission to receive the blankets.

Tariel Neparidze, originally from Shukruti but living in Tbilisi, says that police searched a bag he was carrying too. His family house in Shukruti is also on the brink of collapse, and since early September, he has guarded the protesters at night.

Protesters told OC Media that Neparidze believed there to be danger that ‘someone’ would plant drugs on the protesters, ‘or something like this’.

‘But in reality, he’s awake all night patrolling and checking if people need anything, or covering them up with blankets’, added one protester.

Jubo Tsutskiridze, another hunger striker who was fired after joining the protest, says that he misses his family, who remained in Shukruti.

‘I’m watching my newborn grow up on my phone’, says Jubo.

Jubo says he has also lost a lot of weight, and his sugar levels are rapidly worsening, but like others, he plans to continue the protest for as long as they can.

‘Our hearts are beating and we fight and we will fight till the end while there is light in our eyes’.

Indifference and accusations

Residents of the village have been demanding a response to damage in the village since September 2019, with the protests becoming increasingly acute in recent years.

But the response from the company has frequently been to dismiss the concerns, claiming in some cases that the protesters’ had already been compensated, in others that they were acting on the orders of non-governmental organisations, political parties, or media outlets.

[Read more: Georgian Manganese–linked company attacks critics and media covering Shukruti hunger strike]

The authorities have also failed to engage extensively with the issue, while the Sachkhere City Court ruled in favour of banning protesters from the mine’s entrance and fining them for their actions.

Those protesting have been demanding an independent evaluation and adequate compensation for their homes, which the company has dismissed by publishing the bank statements of protesters who have received partial compensation.

According to protesters, out of around 40 families protesting, 25 have received no compensation, six received the majority of the promised compensation, and the rest received a limited amount of compensation, mostly for land rather than their houses.

The protesters also believe that their village will soon be uninhabitable and they will have to resettle.

‘They closed the school [in Shukruti], churches are damaged, graves are destroyed. We don’t have drinking water. Roads are barely hanging on. The village is practically unable to function’, says Zviad Papidze, one of the hunger strikers.

Despite their placement directly in front of parliament, no government officials or members of the ruling party have visited the protesters.

Two weeks after the protesters’ arrival, Public Defender Levan Ioseliani met with the Shukrutians.

Beka Neparidze, a protester, told Ioseliani that his visit was like ‘a wreath for a funeral’, with others criticising his failure to visit or engage with them earlier.

In response to OC Media’s question as to why Ioseliani had not met with the protesters since they relaunched their protest in March, the public defender stated that he ‘can’t go everywhere’. Ioseliani added that he did not want to make false promises to protesters, as he had limited powers.

Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze, however, claimed on 2 October that ‘such protests often coincide with the election period’, despite the protest having begun five years ago.

‘Since we arrived in Tbilisi, [the government] have not shown any attention at all. If they say something, they come out and defame us’, says Jambuli Macharashvili. ‘Kobakhidze came out and said […] that these people took money.’

‘He should come out and talk to us’, adds Jambuli. ‘We have agreed to sit down with journalists, sit down with lawyers and discuss this issue. But [the government and company] don’t care enough to find out.’