Opinion | Chechen voices are being silenced, even those abroad

Until the fear of collective punishment ends, even the simple act of speaking publicly is a privilege that most Chechens don’t have.

It is impossible to underestimate the role of the internet in modern political life. Many people in the West rely on the internet and social media to learn the news, while diasporas often build a strong online presence to help them advocate for changes at home or fight authoritarian regimes. Yet, even in today’s online age, some groups can be erased.

In Russian-occupied Chechnya, the local administration has created an entire system aimed at preventing dissidents in the diaspora from speaking openly about what is happening back home. Chechens cannot safely criticise the Russian administration ruled by Ramzan Kadyrov — even after leaving their homeland — because of the fear that the lives of their relatives will be endangered.

It doesn’t matter whether a Chechen comments on politics, speaks out against Russia’s full-scale war against Ukraine, criticises the occupation or mobilisation, or mentions something much more mundane — they may still put their family at risk. This fear prevents people around the globe from understanding the real situation in the republic.

Europe-based Chechen activist Ayub — whose family was targeted after he complained in a Telegram channel about a miscarriage of justice in Chechnya — has emphasised that one does not need to be a political blogger or a prominent activist for something like this to happen.

‘Even if someone just posts on their social media about problems with electricity in the city of Grozny, the authorities may come to their house. The person will be dragged away, beaten, and forced to condemn the post if they live in the republic. If not, or if this person lives abroad, their relatives will be the ones kidnapped and tortured’, Ayub told me.

‘That is what happened to me. Just for several comments in Telegram, they threatened my family and sent me a message through them: I needed to shut up, or my family would pay. And all this happened while I was already living in Europe’, he said, noting that this tactic was part of a whole campaign started by Russia's Federal Security Service (FSB).

He also emphasised that his experiences should not be considered an isolated case: ‘Everyone in the Chechen diaspora knows this could happen. It is not new or unusual’.

The oppositional Telegram channel NIYSO — one of the most important Chechen opposition platforms online — regularly writes about the necessity of anonymity and digital security for Chechen people, both abroad and back home. To help keep this privacy, letters from Chechnya are shared anonymously using a dedicated bot. A similar system is used by Chechen blogger Tumso Abdurakhmanov, whose relatives, like those of NIYSO’s leadership, have also been threatened and persecuted by the Russian administration in Chechnya.

At the same time, European authorities rarely show much concern for the safety of Chechen asylum seekers, and despite clear evidence of reprisals, European governments continue to deport Chechens back to Russia. The danger is well documented, yet many European officials still insist that Russia is a ‘safe’ country for return.

The result of all of this is a suffocating silence. Chechens abroad — even those living in democratic countries — learn to speak in half-sentences. They avoid attending political events. Many choose not to speak at all. And the consequences extend far beyond the diaspora. When those most affected cannot tell their stories, the world is left with Russian propaganda, state-manufactured narratives, and cultural clichés.

Many people in Europe are genuinely curious about what is happening in the North Caucasus. They want to understand the Russian occupation, the repression, and the daily realities of life under Kadyrov’s rule, but the voices that should be heard are the very voices being silenced.

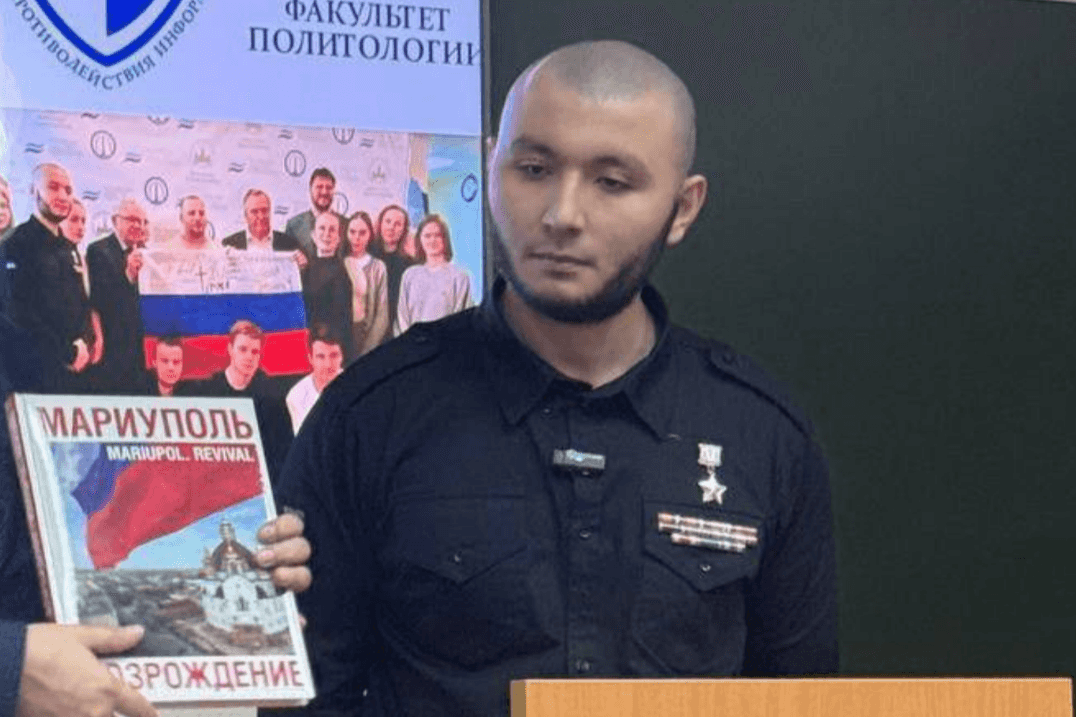

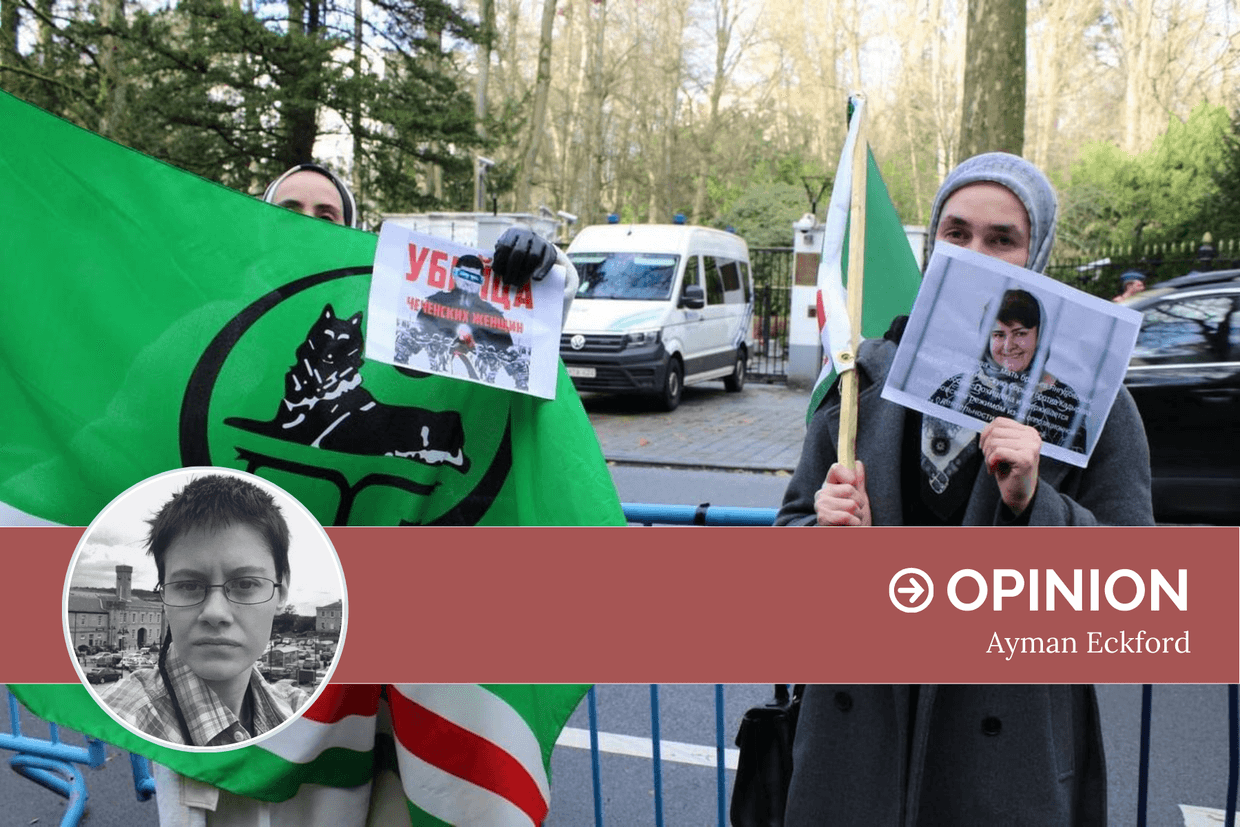

As someone who has organised numerous events about Chechen culture and the miscarriage of justice in Chechnya — from family-friendly colouring and storytelling events to political demonstrations in the UK — I have seen people’s interest firsthand. People in the UK and in the West in general often ask me where they can find more information and how they can learn about what is going on in Chechnya. They believe in the principle of ‘nothing about us without us’ and want real Chechen stories, something beyond propaganda, beyond state-approved influencers, beyond pro-Russian boxers of Caucasian origin who publicly praise Kadyrov. But the tragic reality is that most Chechens who could provide those stories are forced into silence. Many of them avoid even events like those, and refuse to speak online at all.

This enforced silence leads to misunderstanding of Chechen culture abroad, and to the very situation where the deportation of Chechen refugees is possible.

Western audiences, who may influence their governments, know about Chechnya only from programmes about martial arts, occasional sensationalist news stories, and a handful of heavily moderated cultural representations. The complexity disappears. What remains is a bleak caricature, rather than a real society that lives under horrendous pressure. This lack of real Chechen stories makes it significantly harder for Europeans to recognise the severity of the human rights crisis unfolding in Chechnya. The European public, as well as European governments, who are not experts on the region, think that nothing serious is happening because no one is talking about it. They do not understand that this silence is forced on people.

The world needs to hear what is happening in Chechnya, and the internet remains the most powerful tool capable of carrying those stories across borders. But until the fear of collective punishment ends, even the simple act of speaking publicly is a privilege that most Chechens don’t have. As long as this silence is enforced, Europe will not be able to understand Chechnya, the roots of Russian aggression in Ukraine and elsewhere, or the broader dynamics of the post-Soviet space. And without that understanding, it cannot respond adequately to the human rights violations taking place in the region.