For better or worse, Turkish culture exerts a considerable influence on modern Azerbaijani youth culture. While for many films, television, music, and literature from Turkey offer a window into the wider world, some worry it is supplanting Azerbaijan’s own culture.

For better or worse, Turkish culture exerts a considerable influence on modern Azerbaijani youth culture. While for many films, television, music, and literature from Turkey offer a window into the wider world, some worry it is supplanting Azerbaijan’s own culture.

‘Abi, give me a beer’, leaning on his elbow, a young man addresses the bartender in a Turkish manner: ‘abi’ means ‘elder brother’ or ‘friend’. He has a carefully trimmed beard, and on his wrists are bracelets of wood and leather — that’s what the guys on the streets of Istanbul look like.

In the corner of the bar, the guitarist, with a similar beard and bracelets, tunes his instrument. He sings about the hotel of coloured dreams — one of the most famous songs of Teoman, a popular Turkish rock singer.

The bartender wants to apply for a master’s degree in Turkey: ‘I want to go to İzmir. Away from Erdoğan, and closer to the Aegean Sea. There, they say, everything is almost like in Europe…’

This is how a typical Friday night looks in Baku’s bars and restaurants, where young people who are committed to modern Turkish culture gather. In the middle of the day, hairdressers in beauty salons apply hair dye to their clients with one eye squinting at TV screens showing some Turkish talk show. Both are different manifestations of the Turkophilia widespread in Azerbaijan.

In a sense, the Turkophiles represent an analogy to Russian-speaking Azerbaijanis, although it is much more difficult to single them out from the general public. Given the closeness of the Azerbaijani and Turkish languages, the concept of a ‘Turkish-speaking Azerbaijani’ does not exist, but in their speech, Turkophiles tend to use many Turkish words and expressions. In general, this group of people connect themselves strongly to the lifestyle and culture of modern Turkey, including in their appearance, such as their clothes and hair.

A Turkish influx

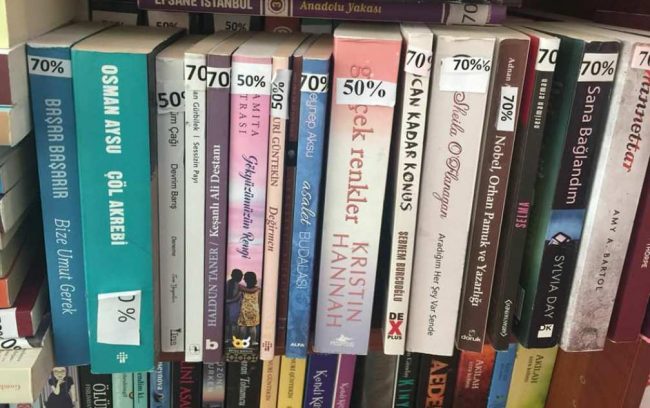

Turkish cultural influences are easy to find in modern day Azerbaijan. There are Turkish restaurants on every corner — from fast-food joints to the most upscale establishments. Cable TV offers a huge range of Turkish channels, cinemas show modern Turkish comedies, while bookstores are stocked with many Turkish language books — both the works of Turkish authors, and translations of foreign literature.

There still remains a lack of translations of books and dubbing of films into Azerbaijani, and not everyone understands Russian or English. So Turkish, with its linguistic similarity to Azerbaijani, continues to be a doorway into world culture for many.

It began after the collapse of the Soviet Union, when a wave of Turkish music, films, and TV shows poured into Azerbaijan, and immediately found a following. They symbolised something foreign and new, unlike Soviet culture.

Russian television channels were still associated with the USSR, and Western films were mostly shown on Russian TV, dubbed in Russian, which many in Azerbaijan did not understand.

There was practically no entertainment for Azerbaijani speakers at the time, and Azerbaijani television stations had not been formed yet.

While Russian speaking Bakuvians could somehow entertain themselves, the inhabitants of the province had nothing else to choose from.

Political considerations also contributed, and in the 1990s, Turkey became like an older brother for Azerbaijan, which was in conflict with Armenia over Nagorno-Karabakh. Since the beginning of the conflict, Turkey sided with Azerbaijan, and in 1993 closed the Armenian–Turkish border.

Returning to Turkic roots

Sanubar Geydarova, a PhD candidate in Sociology at the Baku State University, says that the reason for the mass appeal of Turkish culture in the early 1990s was the desire of many Azerbaijanis to return to their Turkic roots, and purge everything Soviet, including speaking Russian.

Unlike for Russian speakers, there is no heated debate around Turkophilia in Azerbaijan. Turkey is considered by many to be a fraternal state, with almost identical culture and values. they have common ethnic roots, strong economic and political ties, and officials from both countries often describe Turkey and Azerbaijan as ‘two states but one people’.

According to historian Altay Geyushev, a former professor at Baku State University, young Azerbaijanis find Turkey, another Muslim country with secular values, especially attractive. Turkey’s youth, he said, appear simultaneously close in spirit and yet more free than those in their own homeland.

‘In the 1990s, the influence of Turkish culture helped many move away from Soviet patterns, to start thinking in a different way. And the young people who left to study in Turkish universities returned not only with a good education, but also with progressive thinking’, he says.

‘Guys from the lyceum’

The early 1990s also saw Turkish education begin to gain popularity. Azerbaijani students began to attend a state programme for higher education in Turkey, and the first Turkish lyceums — secondary schools — appeared in Baku. Many parents believed that these offered a very high-quality education.

Over time, the trend continued — more lyceums opened and students continued to study in Turkish universities, not only through the state programme, but also with scholarships and sometimes even at their own expense. It was the graduates of Turkish universities and lyceums that formed the core of the new Turkified Azerbaijanis. Former lyceum students, even many years after graduation, often considered themselves to be something of a fraternity — they called each other ‘guys from the lyceum’.

In addition to the lyceums, Turkish kindergartens and preparatory courses for Turkish universities sprang up, and the Qafqaz University opened in Baku.

When the conflict between the Turkish government and opposition figure Fethullah Gülen and his supporters began, it was claimed that almost all of these educational institutions were associated with the Gülenists, and they began to close one by one. Starting from 2014, 11 Turkish schools, Turkish kindergartens, and ‘Araz’ preparatory courses were closed in Azerbaijan, and in 2016 the Qafqaz University was shut.

All of these were a part of the Azerbaijan International Education Center, which was supposedly being controlled by the Gülenists. The schools, as well as the university, were subordinated to the Ministry of Education, the curriculum was changed, and the Turkish leadership and teachers were replaced by local ones.

This caused heated debates in Azerbaijan. Some thought the Turkish lyceums should have been abolished long ago, saying that Azerbaijan has no need for so many foreign schools educating young people in a ‘foreign way’. Others defended the lyceums, claiming the education they provided was much better than in public schools.

Several Turkish schools in Baku managed to survive, and continue to be in demand, although they are private schools and are not cheap. ‘But it’s better to pay once and be sure that they will educate your child well than to place them in a regular school and spend money on tutors for 11 years’, says Sevda Tagiyeva, whose son studies in one of these schools.

Azerbaijani students continue to attend Turkish universities. According to the Turkish Interior Ministry’s Department for Migration, there were 15,000 Azerbaijani students in Turkey in 2017. To compare, there are about 180,000 students in Azerbaijani universities.

Too much influence?

There are some in Azerbaijan who openly express dissatisfaction with the extent to which Turkish culture has penetrated the country. They say that Turks and Azerbaijanis, although belonging to the same ethnic group, due to various historical circumstances that have developed over the centuries, are not so similar.

‘In the 1990’s and even later, the Turkish language played a very positive role in the education of Azerbaijan’s youth. But today I notice a certain abuse of it’, Geydarova said.

According to her, many Azerbaijani children watch cartoons in Turkish from infancy, and eventually start to speak Turkish language better than their own. Among Azerbaijan’s youth, she says there are many who place Turkish culture far above their own. She says that Azerbaijani parents should ‘regulate the Turkification of their children’.

‘Otherwise, soon we will face the same thing we tried to escape in the 1990s: with Turkish-speaking Azerbaijanis in place of the Russian-speaking Azerbaijanis. And it does not matter that the Turks are ethnically closer to us than the Russians. Excessive adherence to the culture of another country means the loss of one’s own national identity all the same’, she warns.

26-year-old Tural Jumshud agrees. He graduated from the Faculty of Turkish Philology at the Qafqaz University, but he does not like being reminded of that. ‘It’s just ridiculous when our young people talk and joke using Turkish phrases. They are simply not educated well enough to use their native language at the proper level, so they resort to the help of the Turkish language, pretending to be Turks and ceasing to be themselves’, he says.

But historian Altay Geyushev believes that it is too early to sound the alarm just because some young people mix Turkish words with Azerbaijani.

‘It doesn’t make them Turks. After all, people aren’t only influenced by books and films, but, above all, by the environment in which they live’, he says.

A wholly different matter, the historian continues, is that over the past couple of years, Turkey has taken a different course, and its influence cannot be considered so positive anymore. Geyushev predicts that in future, Turkey will become less attractive for Azerbaijanis, as it loses something for which it was so loved: liberalism and secularism with a familiar culture.