As media provide a platform for politicians and celebrities to unleash barrages of homophobic statements, activists fight to provide legal protection for queer people in Azerbaijan.

In recent months, Instagram influencer Sevinj Huseynova has become known for her calls for violence against queer Azerbaijanis. A transgender woman, Nuray, became an unfortunate subject of her broadcasts, where Huseynova shamed her for wearing a wedding dress.

Nuray’s body was found burnt in the Garadagh District of Baku less than a month later.

Following the incident, journalist Avaz Hafizli condemned hate speech in Azerbaijani media, and as a result, Huseynova did not exclude Hafizli from her broadcasts, ridiculing him for his sexual orientation.

The Azerbaijani journalist says that life has become harder since the influencer had targeted him, and that members of his family had rejected and abandoned him.

‘I miss my family so much. However, I cannot see them due to safety concerns.’

But Huseynova’s is far from the only person with a wide sphere of influence targeting queer people in Azerbaijan.

In an effort to understand more about hate speech in Azerbaijan, OC Media analysed 100 examples by public figures in the country since 2015.

By searching online for various homophobic slurs as well as the names of some well-known homophobes we selected the first 100 serious examples of hate speech to examine further.

The selection included 65 politicians, 23 celebrities, five representatives of NGOs, and seven others, including a prominent psychologist, a sociologist etc.

A lot of similarities were found in the general attitude towards queer people in the sample, including a tendency to view queerness as an ‘immoral political game’ and a ‘destructive force’ perpetrated by the West targeting the values of Azerbaijan.

Of the examples selected, 88% were published by pro-government media outlets, with independent media making up the remaining 12%. More than 50 pro-government outlets aired and published interviews on topics about queer people in Azerbaijan.

Hate speech in politics

From the sample, it is clear that hate speech is particularly visible in politics. It included 31 former or current MPs, 26 party officials, and eight government officials.

For example, Ilham Aliyev, President of Azerbaijan, was noted to have made queerphobic remarks in a speech to students on the 100th anniversary of the establishment of Baku State University in 2019.

[Read on OC Media: Opinion | Ilham Aliyev's anti-Europe speech foreshadows big changes in Azerbaijan]

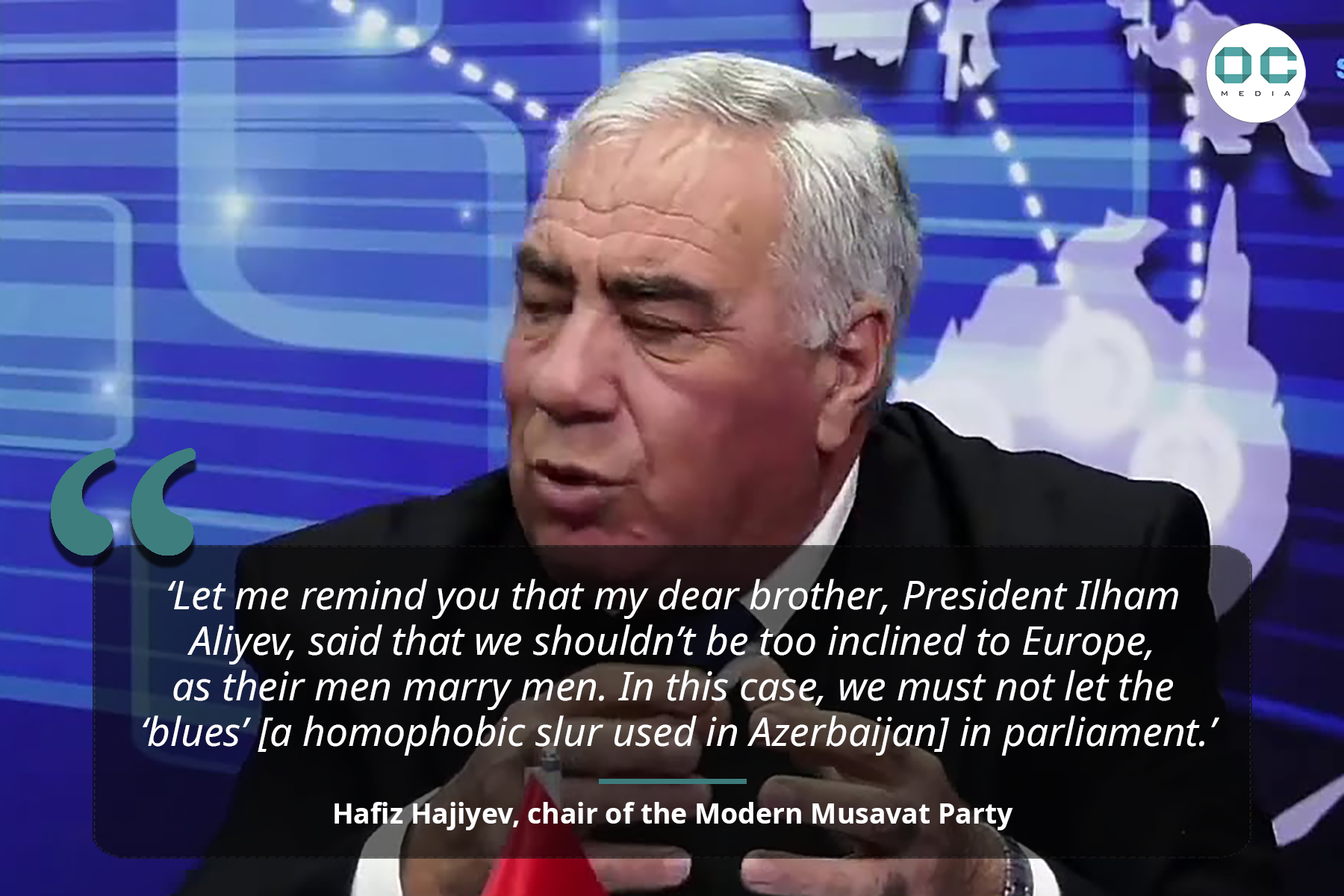

Leading political figures in the country echoed the president’s statement with remarks of their own, such as the chair of the Modern Musavat Party (not to be confused with the New Musavat Party), Hafiz Hajiyev, who called for the exclusion of queer people from politics.

Tural Abbasli, chair of the White Party, made at least six homophobic statements in the past two years, often stressing that he does not support queer people and that being queer contradicted ‘national moral values.’

In one interview, Abbasli associated European influence with queer rights in Azerbaijan.

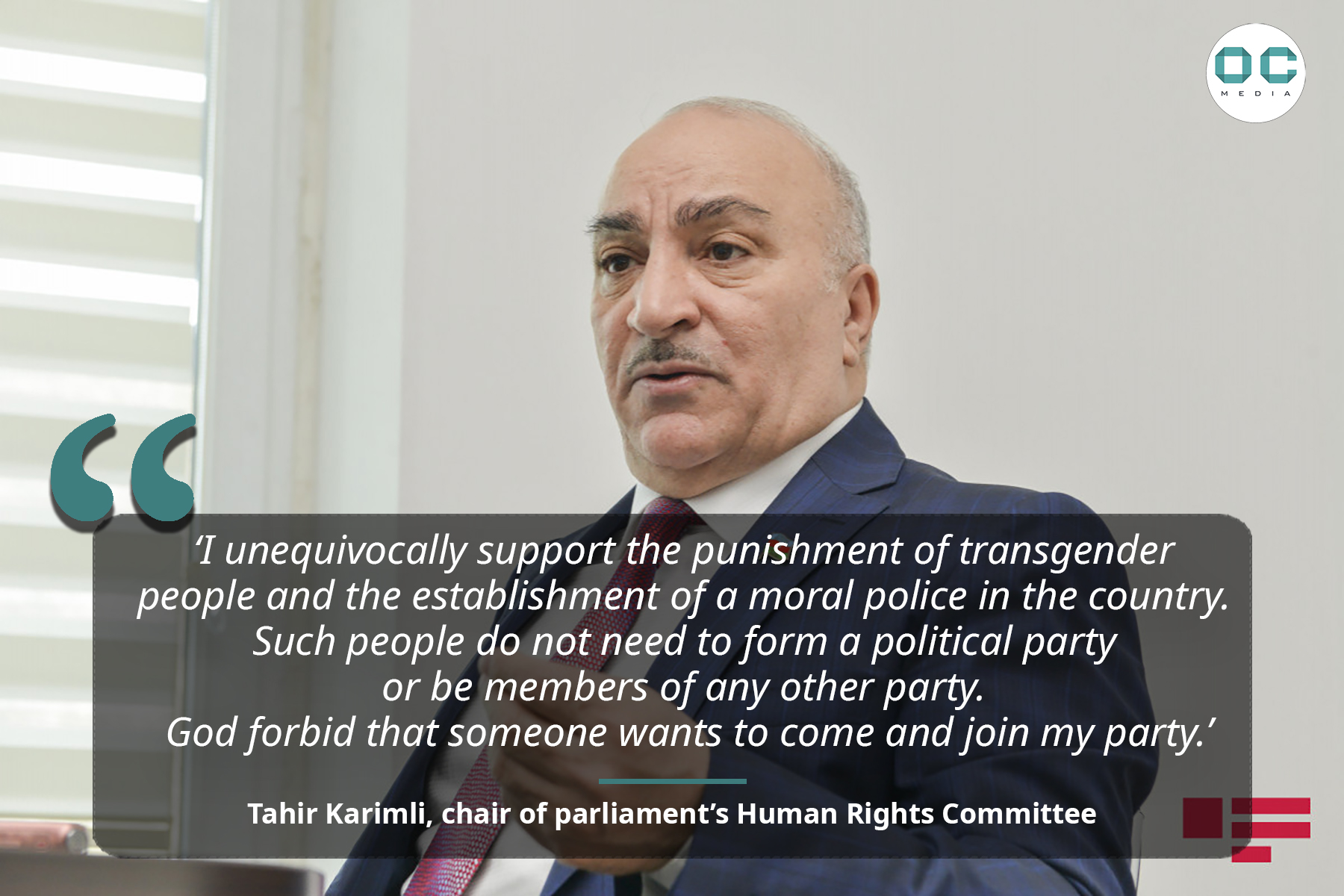

Tahir Karimli, the deputy chair of parliament’s Human Rights Committee, was also quick to denounce a demonstration in front of his office against the murder of Nuray.

Celebrities contributing to the rise of hate speech

Outside the political sphere, celebrities and other public figures also contributed to the conversation following Aliyev’s statements.

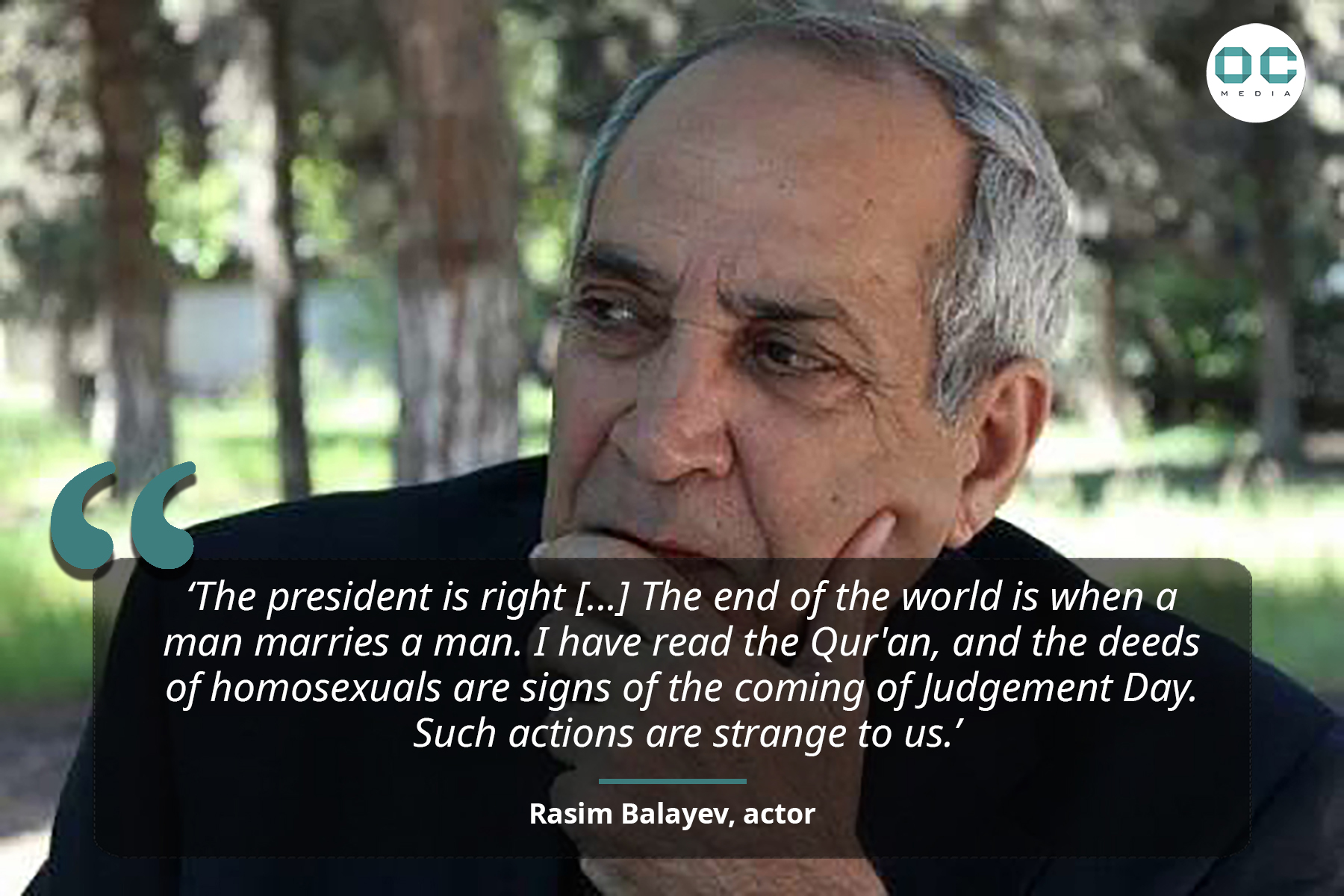

These included Rasim Balayev, a popular actor who has previously participated in campaigns against gender-based violence, who voiced support for Aliyev’s statements in an interview.

In July 2019, TV presenter Ilgar Mikayiloglu called for the ‘destruction’ of queer people on Facebook after he came across a reference to homosexuality in a video game.

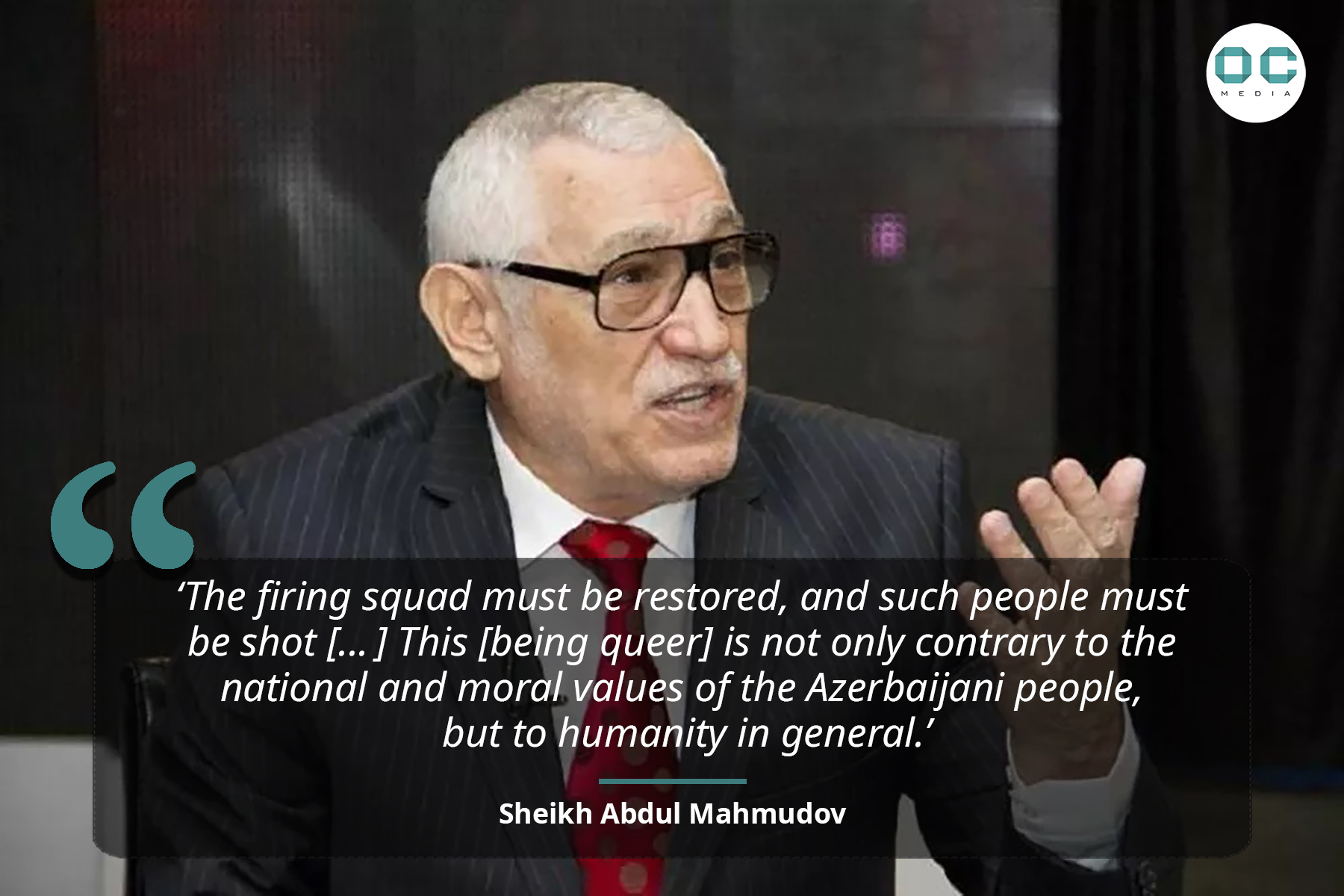

Later that year, People’s Artist of Azerbaijan, Sheikh Abdul Mahmudov, said on local television that gay people must be shot.

The community fights back

According to a report by QueeRadar, a media watchdog monitoring queer issues, such incidents of hate speech have been on the rise over the past three years.

Leyla Hasanova, the co-author of the report, suggests that this has also led to a rise in queer activism in Azerbaijan after 2017.

‘The more pressure you apply on the subject, the bigger the reaction it elicits. The more people express themselves, the more they experience pressure’, she says.

Hasanova thinks it is unethical for journalists to reach out to people uninvolved with queer rights for comments regarding the queer community.

According to her, making queer lives open to public comment takes away their social, cultural, political or legal rights.

‘It is as if everyone can talk about and decide everything related to the fate and life of queer citizens — where and how to live, what socio-political issues should be available for them.’

The organisation’s findings are based on the high number of violent attacks on queer people and the frequency of discriminatory comments made by politicians.

Lawyer Emin Abbasov suggests that actions aimed at inciting national, racial, social, or religious hatred and hostility are prohibited by Article 283 of the Criminal Code of Azerbaijan.

‘The article stipulates that the same acts committed with the use or threat of use of force and by a person using their official position are punished more severely,’ Abbasov added.

However, appeals to authorities regarding instances of hate speech on social media have fallen on deaf ears.

Following the death of Nuray and the rise of homophobic hate speech, local activists collectively appealed to the relevant authorities for the inclusion of queer people under ‘social groups’ protected by Article 283.

Gulnara Mehdiyeva was the only among them to be invited to the State Security Service. She was told that there were no grounds to classify queer people as a social group.

Mehdiyeva believes this form of hate speech should be criminalised, stressing that public figures with authority play a role in the formation of ideas in future generations.

‘Calls for death, or the removal of a group for any reason, in my opinion, should be considered a crime; these people must be held culturally and criminally liable.’

28 January 2022

28 January 2022