While research internationally suggests a link between religion and people’s happiness, does the same stand true for Georgia?

The connection between religion and happiness has been explored in a wide variety of studies, with data pointing to the religious being happier in many countries. However, data from the ISSP survey on religion, which was conducted in Georgia in early 2020, suggests that there is relatively weak evidence of religiosity being tied to happiness in Georgia.

To explore whether happiness was tied to religiosity, four variables related to religiosity were used, including self-assessed religiosity, self-described spirituality and belief in religion, frequency of prayer, and frequency of engagement in religious activities aside from attending services.

On the ISSP survey, a majority of the population (88%) said they consider themselves to be religious to some degree when asked how they would assess their own religiosity.

When it came to spirituality and adherence to an organised religion, most (63%) considered themselves to be spiritual and follow a religion, 14% reported that they followed a religion but were not spiritual, 20% said that they were spiritual but did not follow a religion, and 3% said they neither followed a religion nor were spiritual.

About half (48%) of the public said they never took part in religious activities aside from attending services, 40% did several times a year, and 12% did so on a monthly basis or more.

With prayer, 10% of Georgians said they never prayed, 14% prayed several times a year, and 75% did so monthly or more often. A majority also reported being happy (76%).

The data was included in regression analyses which controlled for respondent age, sex, education level, whether they were working or not, had children in their household, settlement type, ethnicity, and marital status.

When the analysis was run testing whether more religious and less religious people were more likely to be happy, the data suggested no statistically significant association.

Similarly, how frequently people engaged in religious events aside from attendance at non-holiday sermons was not associated with happiness. Frequency of prayer was not associated with happiness either.

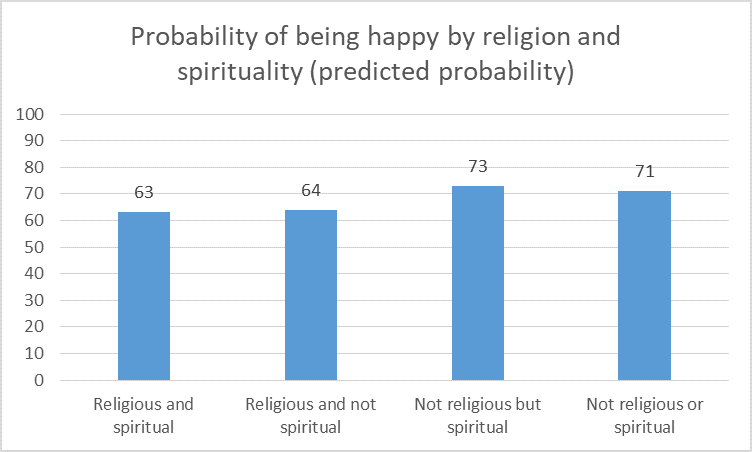

However, spirituality was associated with people’s happiness.

Those who did not follow an organised religion but were spiritual were significantly more likely to be happy than those that reported following a religion. The non-religious and non-spiritual were not significantly more likely to be happy than the religious according to the regression analysis, but this likely stems from the small sample size within this group.

The data is less than conclusive, though still striking. Of the four religiosity variables tested for association with happiness, three were not associated with happiness. The one that was associated with happiness worked in the opposite direction than is usually seen internationally.

This pattern stands in contrast to the general picture globally, calling for further research into religion and happiness in Georgia.

Note: The data used in this article is available here. The results presented in this article are based on a logistic regression model. The outcome variable, happiness, is coded as happy or not happy. The religion variables are coded as follows: How would you describe yourself? (Religious, not religious); Which best describes you? (I follow a religion, I am a spiritual person; I follow a religion, I am not a spiritual person; I don’t follow a religion, I am a spiritual person; I don’t follow a religion, I am not a spiritual person); How often do you pray? (Never, up to several times a year, once a month or more). How often do you participate in religious activities other than attending religious service? (Never, up to several times a year, once a month or more). The control variables included age, sex, education level (tertiary education or not), whether the respondent was working or not, had children in their household or not, settlement type (Tbilisi, other urban, rural), ethnicity (minority or not), and marital status (married or not).

The views presented in this article are the author’s alone and do not necessarily represent the views of CRRC Georgia or any related entity.