Did Russian support help Badra Gunba win Abkhazia’s presidential election?

In the days since the Kremlin-favoured candidate won, authorities have increasingly cracked down on political opponents.

Badra Gunba, Moscow’s favoured candidate, proved victorious in the second round of voting in Abkhazia’s presidential election earlier in March. While it was clear that Russia supported Gunba over his opponent, opposition leader Adgur Ardzinba, the extent that the Kremlin put its thumb on the scale — and if it proved to be a decisive factor in his ultimate victory — continues to be debated.

In theory, the run-off election should cap off an extended period of political turmoil in Abkhazia that began with the introduction of controversial investments legislation that would have provided preferential treatment to Russians. The legislation sparked public backlash, culminating in the resignation of former President Aslan Bzhaniya and the announcement of new snap elections.

At the same time, Russia was clearly displeased by Abkhazia’s public flaunting of its interests, and the Kremlin responded by imposing punitive measures that struck at Abkhazia’s already struggling economy.

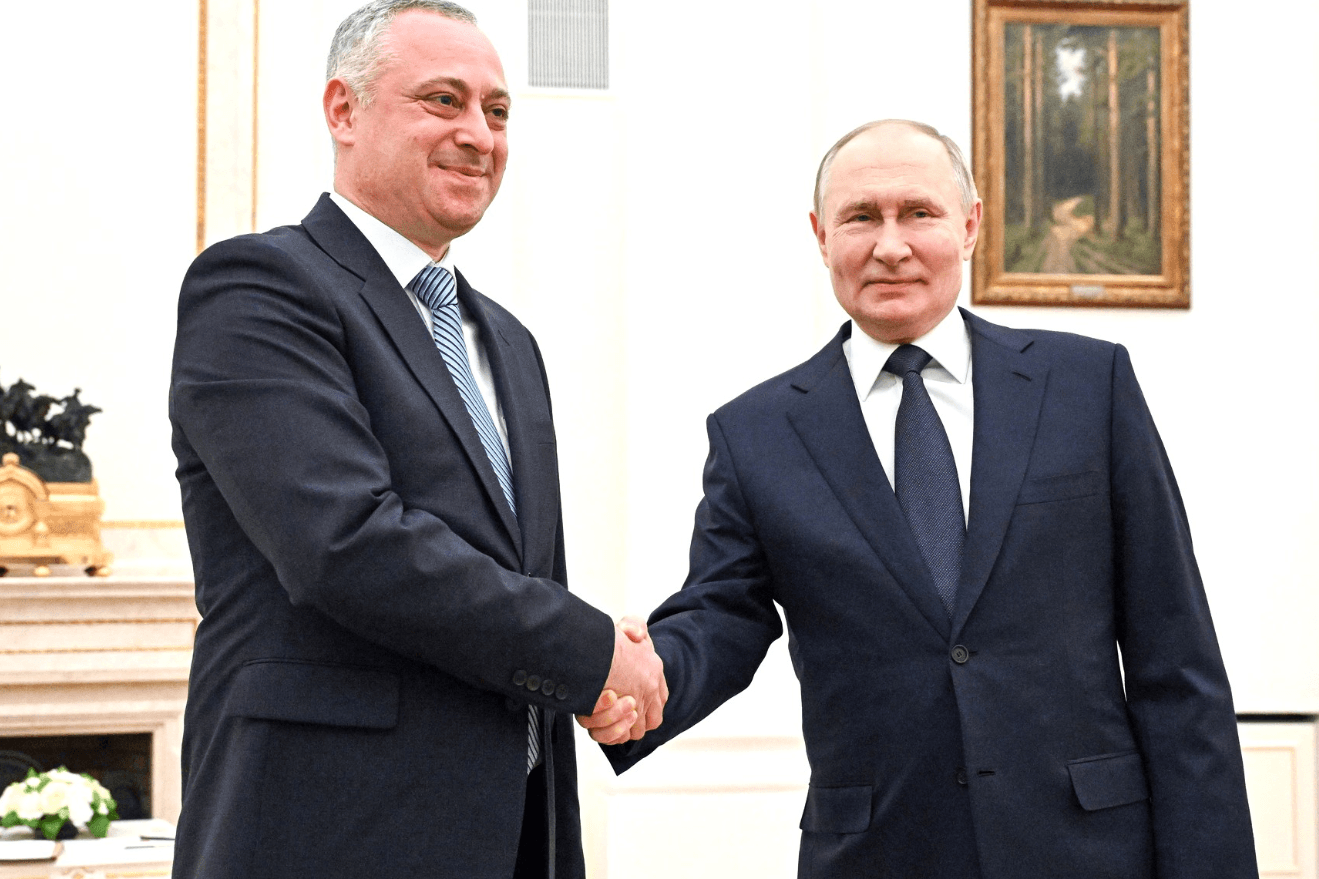

Following the run-off election, Gunba traveled to Moscow and met with Russian President Vladimir Putin. The following day, Kremlin spokesperson Dmitry Peskov announced Russia would send emergency energy supplies to help address the crisis — which Russian decisions had exacerbated — widely seen as a clear sign of rapprochement between the two sides, and that Russia was rewarding Abkhazia for electing its favoured candidate.

Gunba is set to be sworn in as Abkhazia’s next president on 2 April.

Russia’s public support and leverage of Kremlin funds

The most overt illustration of Moscow’s support for Gunba came immediately following a visit to Abkhazia in late February by First Deputy Chief of Staff of Russia’s Presidential Administration, Sergei Kiriyenko, who was himself born in Sukhumi (Sukhumi).

Kiriyenko held a number of meetings at Sukhumi’s main hospital, airport, and schools, during which members of the Abkhazian government told him and other visiting Russian officials what kind of help they needed. Following these meetings, Russian ‘gifts’ began to pour into Abkhazia.

School buses were delivered to Sukhumi in several batches to provide transport for schoolchildren in rural areas.

The Sukhumi Airport, which has been shuttered for decades and is currently being renovated with Russian assistance, saw the arrangement of a test flight from Moscow to Sukhumi and back.

At a colourfully arranged reception at the airport, Gunba and Abkhazian students from Russian universities arrived on a Russian plane, where they were met by a children’s folk dance ensemble. The spectacle was covered by all Russian state-run tv channels.

The main subtext of the media blitz was that only Gunba, if he was elected, would be able to ensure the effective cooperation between Abkhazia and Russia.

Signs of the impact on the ground of Gunba’s leveraging of his connections with Russia also began to appear.

The dilapidated courtyards of apartment buildings began to be urgently repaired, with potholes and uneven areas being refilled and smoothed over with concrete, even on frosty and rainy days.

A similar phenomenon happened back in 2019, when another Moscow-favoured candidate, Raul Khadzhimba, was running for president.

In a form of aggressive ‘campaigning’ that originated from Khadzhimba’s campaign headquarters, citizens were induced to support Gunba’s candidacy via targeted construction works.

Other measures that demonstrated Gunba’s skill at cooperating with Russia, such as the mass medical examination of schoolchildren, also began during the election campaign.

The rollout of the examination programme was presented as the result of an agreement between Gunba and Russia, but in fact, the decision had been made at a meeting between Kiriyenko and Abkhazian Health Minister Eduard Butba. The installation of an angiography device at a Sukhumi hospital also stemmed from that meeting.

Kiriyenko’s meeting with one of the candidates, namely Gunba, was a hint at who Moscow supported. While Kiriyenko publicly stated that Russia would respectfully accept any choice of the people of Abkhazia, in reality it was clear how much Russia was investing in one candidate — Gunba.

‘This has never happened before, that Russia would bet on only one candidate’, an individual close to one of the presidential candidates told OC Media. The individual wished to remain anonymous for security reasons.

‘Usually, the [means] were divided equally, and the agreements of the Russian Presidential Administration were the same with each of the candidates for the presidency of Abkhazia. This time, the new handler showed that it will not be like before, and that Russia is not going to take the choice [of the Abkhazian people] into account. Now it depends on them who will be president’, the source said.

‘Black’ PR and influence operations

After 31 January — the day that Kiriyenko arrived in Abkhazia, a group of Russian journalists and PR specialists also landed in Sukhumi.

For those observing how the events taking place in Abkhazia were covered in both local and Russian media, it was clear that certain politicians, excluding Gunba, were completely banned in many publications.

For example, no news related to acting President Valery Bganba or presidential candidates other than Gunba, including his main competitor Ardzinba, appeared anywhere in Russian media. Local media in Abkhazia tried to maintain a balance, and even state television, whose management openly sympathised with Gunba, covered the campaign in a measured manner, attempting to ensure equal access to airtime for all presidential candidates.

‘There was a feeling that our Badra Gunba was being advertised to Russians and they wanted to convince them [Russians] that he was worthy of becoming the president of Abkhazia’, a Sukhumi resident told OC Media.

‘Or maybe it was so that later they could justify to taxpayers why they invested so much [money] in Abkhazia. In general, it feels like we are being fattened up like turkeys for the slaughter’.

While official Russian media was busy promoting Gunba, anonymous Telegram channels were waging an information war against his main competitor, Ardzinba, who was called pro-Turkish, linked to international NGOs and local criminals, and accused of inciting ethnic hatred. The anonymous accounts said that if Ardzinba won the election, Russia would turn away from Abkhazia, stop supplying electricity, and curtail all social and economic projects. Each of Ardzinba’s public speeches was subjected to careful analysis and dissected by unnamed analysts — excerpts of his speeches, often taken out of context, were republished anonymously.

Legal threats

Russia’s multi-faceted support for Gunba also included legal threats and warning from Russia’s Investigative Committee, which made two statements that Russian law enforcement agencies would protect Russian citizens living in Abkhazia.

The first time came when Ardzinba’s headquarters allegedly threatened the Armenian population of Abkhazia because they voted en masse for Gunba in the first round of the presidential election.

The second time, the Russian Investigative Committee made a statement on the day of the run-off election when supporters of Ardzinba were accused of opening fire and overturning a ballot box at one of the polling stations in the village of Tsandrypsh in the Gagra region.

‘The Russian Investigative Committee has opened criminal cases under a number of articles of the Criminal Code of the Russian Federation, including terrorism, on the facts of offenses and crimes committed against Russian citizens who also have Abkhazian citizenship’, the statement read.

It was the first time in the history of Abkhazian elections that Russian law enforcement agencies responded to any alleged violations of the electoral process.

‘These are our elections, these are our criminals. We have our own legislation. We must judge our criminals ourselves. Otherwise, how can we prove that we are a state’, a Sukhumi resident told OC Media.

Post-election crackdown

Despite the wide-ranging support from Moscow, Gunba was unable to achieve a decisive victory over Ardzinba. Out of 100,000 voters, 44,000 voted against Gunba.

Many of those who openly supported Ardzinba are now expecting repression from the new government.

In his post-election statements, Gunba publicly declared that it is necessary to overcome the split in society, and does not intend to divide the people into ‘us’ and ‘them’.

Despite the promises, there have been signs that this repression has already begun.

When journalist Inal Khashig, who criticised both former President Aslan Bzhaniya and Gunba’s election campaign, was declared a foreign agent by Russia, Gunba did not speak out.

Gunba’s radio silence on the persecution of Khashig preceded another wave of political communications that highlighted cooperation with Russia.

On 11 March, the anonymous pro-government Telegram channel Sovmin published a post about what Gunba had accomplished so far. The list included a meeting with Russian President Vladimir Putin, where they reportedly discussed key issues for the Abkhazian people, including support for the energy sector, tripling the quota for Abkhazian schoolchildren to vacation in the Russian camp Artek, Russia’s approval of the allocation of funds for the restoration of important memorials for Abkhazia, and more.

‘There’s more to come’, Sovmin wrote.

An unnamed political analyst told OC Media that against the backdrop of news about another round of humanitarian aid from Russia, there would be more repression of activists and journalists.

In order to clear the field for unpopular decisions and eliminate pockets of resistance in the form of youth movements and journalists who draw attention to treaties and agreements that are unfavorable for Abkhazia, some believe Russia will impose sanctions against them, with the tacit consent of the authorities.

‘Everyone who criticises the government’s decisions will be declared Turkish, Georgian, [or] British agents. Civil society and independent journalism will be destroyed. And in about a year, an active process of integration with the Russian Federation will begin’, the analyst said, adding that he wished to remain anonymous in order to be able to voice his position for at least some time without giving a reason to label him a foreign agent or traitor.

For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status.