Beka Grigoriadis has for months protested daily outside the Georgian parliament, against the prosecution of his son, Lazare Grigoriadis, who is on trial for his role in the foreign agent law protests. He speaks about the case against his son, the political situation in Georgia, and how those who fought alongside Lazare had now abandoned him to his fate.

Since he began protesting daily on 29 May 2023, Beka Grigoriadis has become a regular fixture outside parliament.

Grigoriadis, 42, speaks to us through stitches, having sewn shut his mouth and a single eye on 20 June. He was inspired by a group of striking miners who he believes had legitimate issues with their employer and living conditions.

Sewing his eye and mouth, he says, was a signal to the government that ‘it is a difficult thing to play with me’.

‘It’s horrible. When your lips are sewn like this, they somehow start to stick together, and when you open your mouth, it rips. That happens every morning.’ he says. He eats a lot of liquids, like yogurts, but says he feels very weak and has lost over 30 kilogrammes.

Since Lazare’s arrest on 29 March 2023, his father has attended most major protests against the government, and many smaller ones.

Always eager to talk about his plans, his protest, and his son, Beka has spoken openly with us on many occasions.

He goes to parliament every day at 20:00 with posters of Lazare. He sits there, mostly in silence. Sometimes, he has a small speaker with which he plays music — the anthems of the EU, Georgia, and Ukraine, as well as Ukrainian and Georgian songs.

He is often accompanied by a small group of supporters — his brother, young activists who fought against the foreign agent law, and others who show up from time to time to ask how he is and express support.

He remains constantly under the watchful eyes of a dozen or so police, stationed nearby.

Beka’s dedication to securing his son’s release is matched by a righteous anger. And after over three months of protesting, and with his lips and eye sewn shut, his anger seems only to grow by the day.

While usually directed towards the government, he also resents local human rights groups and the tens of thousands of people who fought against the foreign agent law who he says have now betrayed and abandoned his son.

‘This is all politics’

Having studied economics at Tbilisi State University, Beka Grigoriadis now runs a construction company. ‘Right now, 80% of bus stops across Georgia with advertising boards were installed by my people’, he says proudly.

But Beka had not always wanted to be in the construction industry. In 2016, he wanted to run as an independent candidate for MP.

‘They [ruling party] didn’t let me, they treated me very badly’, he says, claiming the authorities planted drugs on him. He was arrested and received two years of probation and a five-year ban from running for office.

But his political activism did not end there. He briefly worked with Giorgi Vashadze, a former UNM politician who established his own party, New Georgia, in 2016.

‘Giorgi had good ideas, he brought new faces, youth, he had very cool projects. I liked it’, he recalls. ‘But then Giorgi decided to create alliances with different politicians, which I didn’t like and I left’.

But he remained politically active.

‘I’ve been to most protests organised by opposition parties. It doesn’t matter for me which party it was, I was going to all the protests where they were criticising the government.’

Beka says his son Lazare was also interested in politics, with the two attending several protests together.

‘How can you not be interested?’, Beka says. ‘The social situation in the country — this is all politics. If you want to live like you want to live, you should be interested in politics.’

During the March protests against the foreign agent laws, Beka says he could not attend due to illness, and was forced to follow from a distance.

He says his son was guided by a sense of justice.

‘When they are after people, he always had the desire to go out [to protest] and help those young people.’

He recalls when the two of them were among the thousands of protesters to march 10 kilometres to the Central Election Commission, following the 2020 parliamentary elections.

‘When there was a dispersal outside the Central Election Commission, robocops [riot police] wanted to arrest a girl, and he [Lazare] tried to stand up for her; he wanted to help her and he got detained instead. They didn’t release him on bail. They detained him for five days.’

He remembers that the first time Lazare expressed a desire to attend a protest was on 20 June 2019, known as Gavrilov’s Night.

‘When they started dispersing people, I had already left’, he recalls.

‘When I got home, I was watching live with my wife, how they were running after people in different yards. Then I saw Lazare standing outside the Opera House. They [the riot police] were shooting and my son was standing facing them.’

‘My god, I was terrified. I thought of going, but the road was closed. I called Lazare, told him to get a taxi and leave, that they may arrest him. He told me — I’m a minor. He was only 17 then.’

Eventually, Lazare obeyed and went to his grandfather’s house.

‘Georgia was not ready for such an appearance’

Despite Beka’s relentless campaigning for his son’s release, rumours have persisted that their relationship is a troubled one.

But Beka insists that while they have had disagreements over the years, they remain close. ‘I did everything that I could for the kid’, he says.

Beka says that aged 14–16, Lazare fell in with a bad crowd, causing tension within the family.

‘Then one day he showed up with green eyes, green hair, green eyebrows. He told us: “you didn’t like me that way, then accept me like this”.’

‘We got our wish’, he says with a laugh.

‘I almost got a heart attack when I saw what he did with his eyes, but what can you do’, adds Beka, referring to Lazare’s distinctive facial tattoos, which resemble eyelashes.

Beka said he was worried that ‘Georgia was not ready for such an appearance’.

‘Some radical groups roam the street with batons and I know my son: if someone says something to him, he won’t tolerate it. He is not like that, he’s a brave man.’

And Beka’s concerns appear to have been well-founded. Since his arrest, officials and pro-government media have focussed extensively on Lazare’s appearance, attempting to discredit him with homophobic dog whistles about his ‘confused orientation’.

Indeed, Beka thinks his son’s appearance was the reason he was targeted for arrest in the first place.

No justice

What drives Beka to continue to protest daily is the sense of injustice he feels at his son’s treatment by the authorities.

He recalls the night of Lazare’s arrest on 29 March, 20 days after the protests against the foreign agent law succeeded and having turned 21 in the interim.

That night, he was staying at a friend’s house.

‘Almost the entire night passed and for 10 hours they didn’t allow him to call home or to a lawyer. They gave him his phone, pretending he could call, but the moment he unlocked the phone, they took it from him. They don’t allow him to call.’

His father learned of his arrest on 30 March and has not been allowed to speak to his son since. Prosecutors requested he be barred from communicating by phone on the first day of his arrest, a request granted by the judge overseeing his case.

Beka is also certain his son is innocent of the charges levelled against him, of throwing Molotov cocktails at police.

‘I’ve seen the videos, he was throwing stones, I saw it’, he says.

The bottle the prosecutors claim is a Molotov cocktail, Beka says, is a bottle of Coca-Cola. ‘You can even see the label.’

‘The videos are bad quality on purpose, so it’s hard to see who is depicted’.

Beka does not believe that the courts will provide justice, citing the widely reported existence of a ‘clan’ within the judiciary working with the ruling party on politically sensitive cases.

Beka has himself also come under pressure.

Since he started his protest, he has been fined three times on administrative charges, coming to a total of ₾6,300 ($2,400). Beka says he is unable to afford to pay the final fine.

‘No one knows how brave Lazare is’

When speaking with Beka, despite the treatment he says he and his son have received from the authorities, much of his anger is reserved for those who protested alongside Lazare who he says have now ‘forgotten about him’.

‘My protest is also against those people, who fought alongside Lazare, their brother, their comrade in arms, and then abandoned him’, he says.

‘These people are not acting right, this is not bravery, this is not Georgian, this is not a fighting spirit.’

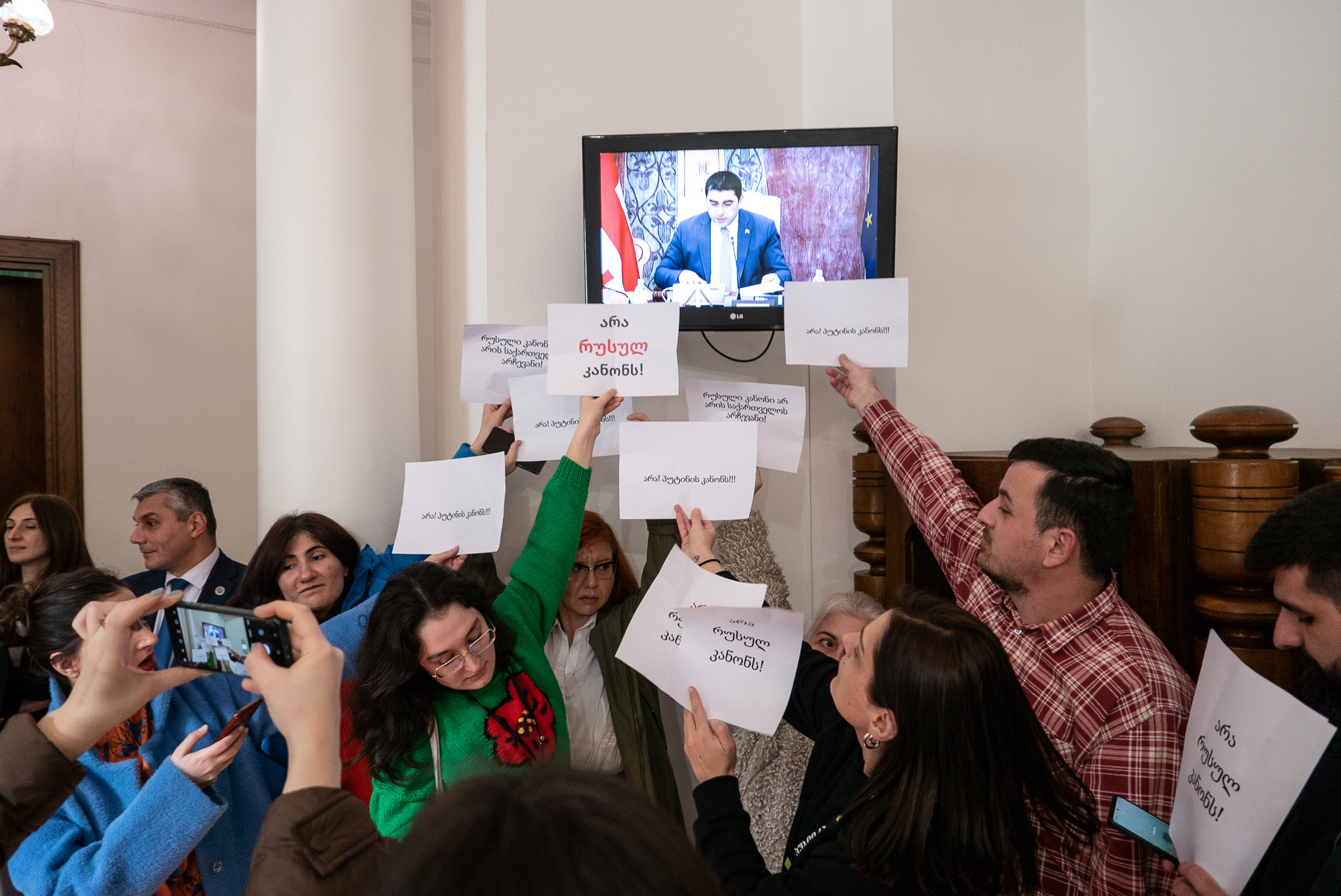

The protests against the foreign agent law, organised by several local NGOs, lasted just days before the government was forced to back down.

‘Not only the NGOs, but my protest is aimed at many people. To the people who forgot my Lazare because of some gossip and watching Nadezhda TV’, he says, mockingly translating the name of the pro-government TV channel Imedi into Russian.

‘No one knows how brave Lazare is, what a soul he has’.

Despite feeling alone, Beka remains defiant.

‘I will free Lazare, and when this happens, I will disappear like I was before’, he says. ‘I have my business, I am successful, and I don’t want any other responsibilities’.

But he says, he is also ready to make the ultimate sacrifice for his son if necessary.

‘I will give up the most precious thing I have — my life — to save Lazare, but not yet, I will try everything else first.’