Explainer | How a controversial investments agreement led to the downfall of the Abkhazian president

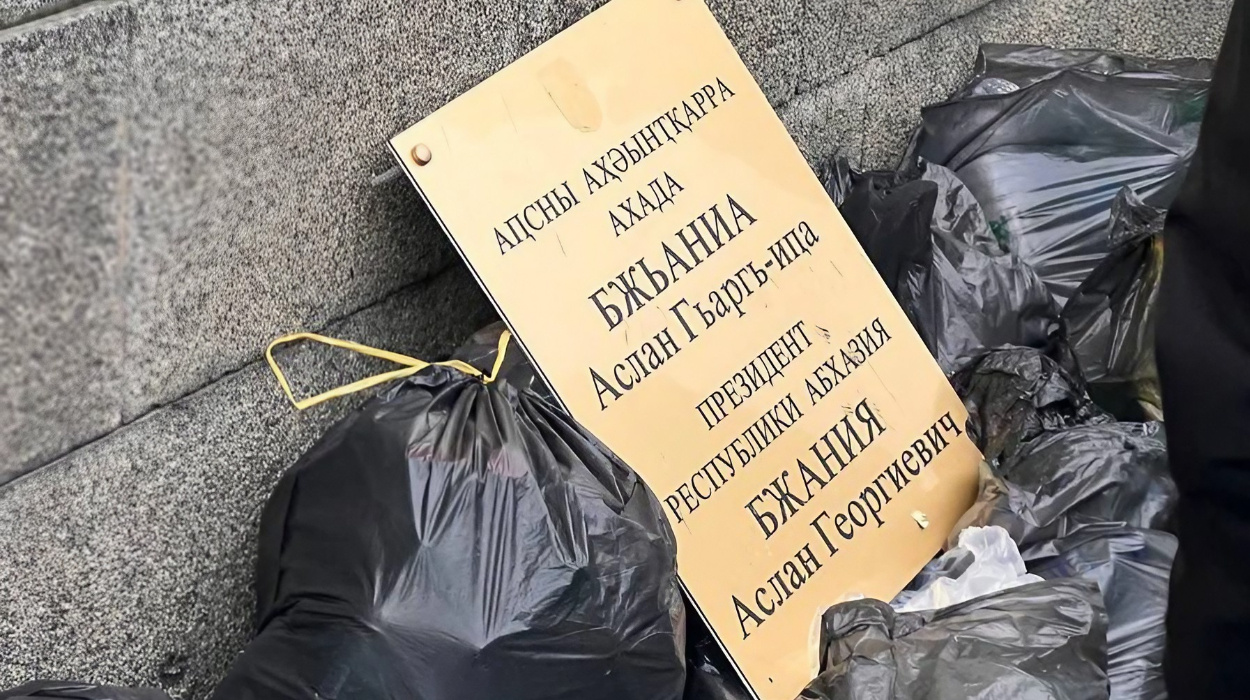

In the early hours of Tuesday, Abkhazian President Aslan Bzhaniya announced his resignation after days of protests centred around a controversial agreement on Russian investments. Bzhaniya still intends to run in the upcoming presidential elections, which are expected to take place in February.

Over the course of less than two weeks, discontent over the proposed legislation grew and morphed into a protest movement that brought down the Abkhazian government.

On 30 October, an agreement on the investment activities of Russian legal entities in Abkhazia was signed in Moscow by the Abkhazian Economic Minister, Kristina Ozgan, and the Russian Economic Minister, Maxim Reshetnikov.

According to the legislation, the Abkhazian government would exempt registered Russian entities launching investment projects in Abkhazia from property taxes for eight years upon their registration in Abkhazia.

They would also receive tax relief on VAT.

The government would also exempt the company from customs duties for building materials or equipment imported into Abkhazia for the implementation of the project.

The agreement has been met with harsh criticism from the opposition; various youth groups, including the Hara H-Pitsunda (‘Our Pitsunda’) movement, which previously took to the streets to protest the handover of a Soviet-era state dacha to Russia; and the Council of Elders, a traditional advisory body.

When the draft bill was submitted to parliament on 7 October, MPs suggested 20 amendments to the document — but only two of these amendments were adopted in Moscow before the document was signed.

Opposition announces moves to counter legislation

At a public meeting on 5 November, Levan Mikaa, the head of the Committee for the Protection of the Sovereignty of Abkhazia, announced that opposition groups would do everything possible to prevent the ratification of the agreement.

‘We need to consolidate all forces to oppose the entry into force of the investment agreement. We will use all available means, including protests’, Mikaa said.

Following this gathering, a headquarters was established to better organise the opposition in order to oppose said ratification.

Three days later, a parliamentary committee meeting was held, during which Ozgan explained to MPs why only two amendments were adopted. Following the meeting, the committee made a unanimous decision to recommend the ratification of the investment agreement, but with the proviso that a law on the legal status of multifunctional complexes would be adopted beforehand.

The concept of multifunctional complexes has never existed in Abkhazia. However, the investment agreement explicitly states that an investor can build such a structure.

On 11 November, the parliament adopted a law on the legal status of multifunctional complexes, seeking to fill the gap in Abkhazia’s legislation. According to the new legislation, these multifunctional complexes can only be used for commercial purposes — living in the complexes is prohibited.

However, members of the opposition have warned that the law is not likely to be enforced. They also argued that potential owners of such complexes could still sell the premises for residential use, as is often the case in the neighbouring Russian city of Sochi, where the owners of such real estate transfer their property holdings to the residential category through the courts.

Following the adoption of the law, several opposition members — including Omar Smyr, Harry Kokaya, Ramaz Dzhopua, and Almaskhan Ardzinba — attempted to speak to the MPs who had promoted the agreement. While one of the MPs, Alkhas Bartsits, was able to quickly leave the parliament and avoid speaking to the opposition, another, Almas Akaba, got involved in a scuffle.

That evening, after an opposition meeting in Gudauta, police along with members of the State Security Service and the Interior Ministry’s Special Rapid Response Unit (SOBR) stopped a car carrying opposition politicians who had taken part in the scuffle. The opposition members were detained, along with another passenger, Aslan Gvaramia, who had not taken part in the brawl.

A video showing the opposition members being detained was then shared on social media, which sparked public outrage. In response, the opposition headquarters, originally set up to block the ratification of the investment agreement decided to block the three bridges leading to the capital city Sukhumi (Sukhum) to protest against the arrests.

Protests and blockades

At 22:00 on 11 November, opposition protesters blocked both bridges over the River Gumista to the west of Sukhumi, as well as the bridge over the River Kodori, located to the east. They vowed to only unblock the roads if the detained opposition members were released.

Negotiations between the government and the opposition began, mediated by members of the Public Chamber of Abkhazia, an advisory body to the president.

Sokrat Dzhindzholiya, a member of the Public Chamber, told protesters the following day that the opposition members would be released by a court decision. According to Dzhindzholiya, administrative cases had been filed, after which the Sukhumi City Court decided to close the cases and release the detainees.

At 17:00 on 12 November, all five detainees were released, and in response, protesters unblocked the bridges.

According to some opposition members, the whole series of events — the detentions, the footage being leaked, and a quick and peaceful resolution — was an act of intimidation from Bzhaniya’s government.

‘The authorities showed that they have power in their hands, and that the special forces will lock up everyone who is dissatisfied with their decisions. Everything was done on the eve of the supposed ratification of the investment agreement. I think that this was the goal of the show’, a member of the opposition who wished to remain anonymous told OC Media.

A lull, and then an escalation

While one crisis was averted, the authorities prepared for further unrest.

The ratification of the agreement on Russian investment was expected to occur at the next session of parliament on 15 November. In preparation, the authorities added military equipment along the perimeter of fencing surrounding the complex of government buildings.

As the parliamentary session began, people began to gather at the complex, including both opposition members and government supporters.

During the process to approve the parliamentary agenda, MPs voted to remove the agreement on Russian investment from consideration. According to Lasha Ashuba, speaker of the parliament, the decision to withdraw the legislation was made after some MPs refused to make a decision, citing pressure from the growing crowds.

Despite the ostensible concession, protesters were still not placated, and then began to demand the legislation be considered and voted against.

‘We are not happy with the postponement of this issue. We demand that MPs vote against the agreement for the oligarchs’, one of the leaders of the opposition, Adgur Ardzina, told the crowd.

By this time, it was clear that the investment legislation was not the only issue motivating protesters to show up outside the parliamentary session.

‘The president does not take into account the opinion of the people; he is not interested in the opinion of the Council of Elders. But the head of state must consider the opinion of the people. He does not want us, and we do not want him’, a pensioner protesting in front of parliament told OC Media.

‘I want to graduate from university, work, gain experience, and then open my own business. I already have some developments. But if the oligarchs come here, I am afraid that there will be no place for me and people like me. The best lands will be sold’, a student told OC Media.

Many women also attended the protests, including the widow of a veteran of the 1992–1993 War in Abkhazia, who attended the protests in memory of her husband.

‘I don’t understand what our men fought for — so that today we ourselves can sell everything to Russian oligarchs?’ the woman told OC Media.

As the number of protesters grew, so did the crowd’s anger at parliament’s failure to consider the ratification issue.

Eventually, a group of protesters managed to gain access to a military truck. They tied one end of a cable to the truck, the other end to the fence around parliament, and managed to tear down a section of the fence.

The crowd then swarmed through the gap in the fence and entered the yard surrounding the parliament. Some zealous protesters went further, breaking the windows of the building and going inside.

At this point, MPs, members of the Cabinet of Ministers, and Bzhaniya left the government complex to seek refuge in the State Security Service building, located around 300 metres away.

In response, opposition members began calling for Bzhaniya and his government to resign.

Bzhaniya hedges, and then caves

At 21:30, Bzhaniya announced that he was ready to resign, but only on the condition that the current Vice President, Badra Gunba, would become acting president, and that the rest of the government would keep its previous composition.

The opposition was not satisfied with this arrangement, and the protests continued. Members of the opposition kept up their occupation of the government complex, guarding it against attempts from authorities to seize it back.

Later that night, Bzhaniya left Sukhumi for his ancestral home in the southern village of Tamishi (Tamysh).

The next day, at 13:00, he met with his supporters at the village school. He once again announced that he was ready to resign as president, but highlighted that he intended to continue his political career, saying he would run again for president in the 2025 elections.

The same day, a government meeting was held at the village hotel in Tamishi, which informally belongs to Bzhaniya. The Cabinet of Ministers reported that the functioning of all official government agencies was under their control. A closed meeting with MPs was also organised.

The next day, negotiations were held between the authorities and the opposition, with mediation by MPs and members of the Public Chamber. In addition to Bzhaniya’s resignation, the opposition demanded the resignation of Prime Minister Alexander Ankvab and the heads of the Ministry of Internal Affairs, the State Security Service, and the Special Rapid Response Unit. The authorities categorically refused the conditions.

On 18 November, Ashuba announced that direct negotiations would be held between the authorities and the opposition.

That evening, opposition leaders Adgur Ardzinba, Levan Mikaa, and Kan Kvarchia met with Public Chamber member David Pilia, Vice President Badra Gunba, and the head of customs, Otar Khetsia, at the Ministry of Defence. The negotiations continued late into the night.

At 03:00, the negotiators reported that they had reached a consensus. An agreement was signed, according to which Bzhaniya and Ankvab would resign and Gunba would become acting president, while Valery Bganba, a former Speaker of Parliament, would become acting prime minister. All other members of the government would keep their positions.

Later that day, a special session of parliament was held, during which the MPs almost unanimously accepted the president’s resignation — of the 31 MPs present, 28 voted for, one voted against, and the remaining two spoiled their ballots.

Leaks and revelations

While Bzhaniya’s resignation appears to have blunted the crisis as it currently stands, the saga has not yet ended.

Protesters who stormed the parliament discovered a trove of internal documents that have further roiled Abkhazian society and led to widespread anger.

OC Media cannot independently verify the authenticity of the documents, but pictures purportedly of the files have already been widely circulated across social media.

One document appeared to reveal that Bzhaniya’s government had kept a list of ‘disloyal persons’, which included ‘all independent journalists’ in Abkhazia, one blogger told RFE/RL.

Along with names, the list detailed the individuals’ bank accounts and other financial information, personal data, and other information.

Another document showed how the government had made a practice of gifting firearms as a personal reward to a variety of well-known figures, including Tigran Keosayan, a controversial Russian media personality who is married to Margarita Simonyan, the editor-in-chief of the Russian state-media outlet RT and one of the Kremlin’s most famous propagandists.

Bzhaniya’s government also allegedly granted citizenship on a personal basis, while simultaneously working to restrict the process of naturalisation for those in the Abkhazian diaspora in Turkey and the Middle East. The documents revealed that in general, Bzhaniya’s government was pursuing a policy of limiting Turkish influence on Abkhazia. Both policies were directly ‘dictated by Moscow’, Abkhazian media claimed, with the ultimate goal of ensuring that Abkhazia remains internationally isolated and reliant upon Russia.

The most controversial revelation from the seized documents, and the one that appears to have most angered Abkhazians, were details of widespread corruption and plundering of public funds, especially concerning money redirected into the pockets of Bzhaniya and his allies.

‘Public money was spent at Bzhaniya’s discretion, as though it were his personal fortune rather than taxpayer resources’, wrote the Abkhaz World media outlet.

‘Enormous sums, amounts pensioners, teachers, and civil servants could only dream of, were handed out to Bzhaniya’s supporters, both in cash-filled envelopes and directly’.

Significant sums were also directed toward state-run media, which in turn were used to promote Bzhaniya.

‘Essentially, Bzhaniya was preparing to fund his re-election campaign using public money’, Abkhaz World said.

While a date for the presidential elections has not officially been announced, it is expected that they will take place on 15 February 2025.

However, an initiative group of lawyers, journalists, and public figures working on constitutional reform have suggested that the date be pushed farther back. They have also proposed that parliament reform the distribution of powers between the executive and legislative branches during this time.

‘The 1994 Constitution of Abkhazia was adopted at a difficult time for the country and allowed us to go through this period with dignity. However, the reality has changed. Our basic law no longer meets the challenges facing modern Abkhazia and needs urgent corrections’, the group said.

For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status.