A group of students at Ilia State University (ISU) in Tbilisi have spontaneously come together to form a new student group in protest against the rigged parliamentary elections — with one form of protest including organising their lectures on the streets.

On 19 November, the Iliauni Student Movement at Tbilisi’s most progressive university organised their first publicly visible initiative, taking the lead from Georgian writers Lasha Bughadze and Ana Kordzaia-Samadashvili, who delivered a series of outdoor lectures.

‘This is no time to continue as usual; this is a form of protest by which we say we are fighting but also continuing to study’, Lile Mshvenieradze, part of the Iliauni Student Movement and a literary studies student there, tells OC Media on 21 November.

Nika Kereselidze, a second-year law student at ISU, says the format allows them to continue their studies in a new way while being ‘closer to the people who are defending our country right now’.

Kereselidze claims that the ruling Georgian Dream party stole the elections from them, a sentiment widely shared among Georgians critical of the government following reports of various irregularities during the 26 October vote.

‘I don’t think it’s a theory anymore,’ he says after a full day of lectures, culminating in one on censorship, delivered by Gia Bughadze, a prominent Georgian artist, arts educator, and former Rector of the Tbilisi State Academy of Arts.

‘It was about censorship in the Soviet Union. Nothing’s really changing’, Kereselidze says, emphasising the irony of the situation.

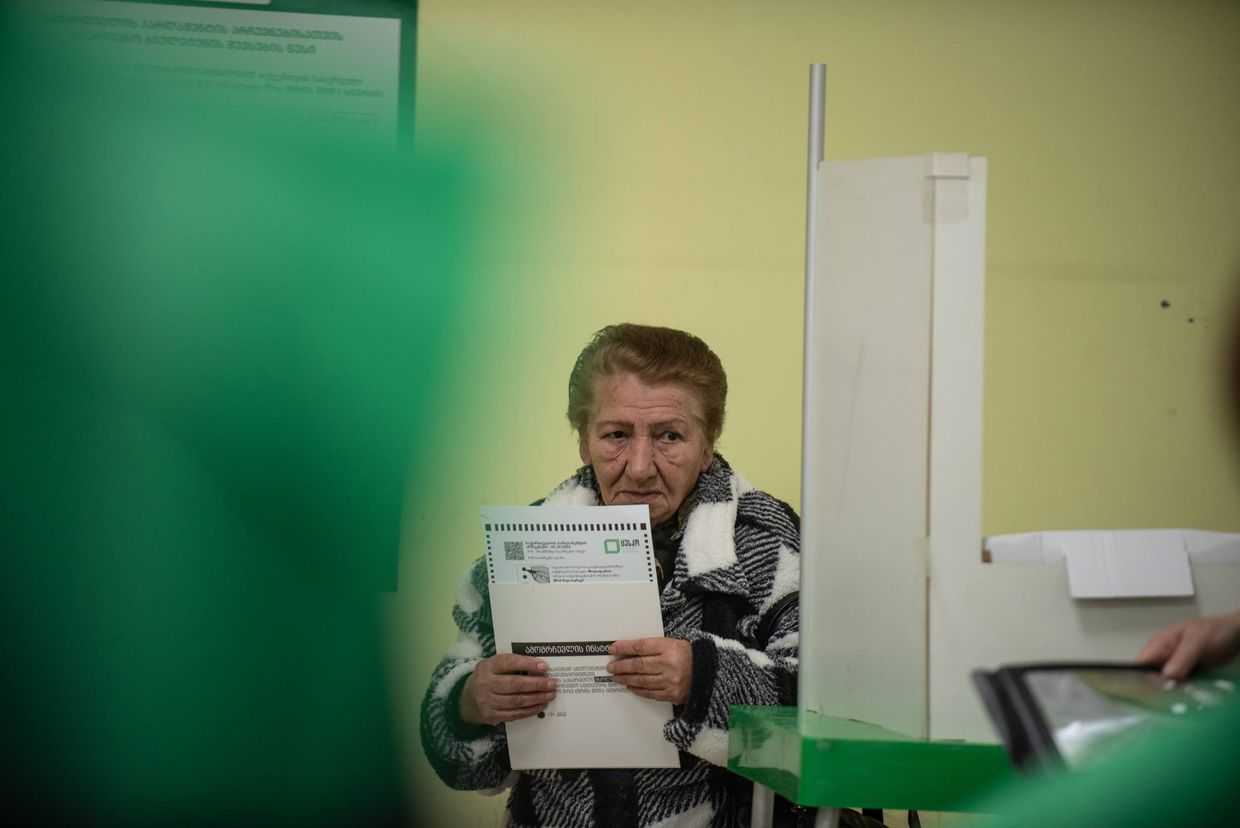

Ani Keratishvili, a third-year sociology student at ISU, shared that this was her first time voting and that she also volunteered as an election observer at a Tbilisi polling station, only to witness the elections marred by ‘fraud and intimidation of voters’.

‘When elections like this take place in the country, it’s no longer just about a specific university or particular individuals’, Keratishvili says.

The Iliauni Student Movement emerged as a mobilised group in solidarity with students at Batumi’s Shota Rustaveli University, who have been staging a sit-in since 14 November in protest against the rigged parliamentary elections.

The Iliauni group launched their first and most public initiative — a continuous teach-out — just hours after police forces descended on a protest encampment in Tbilisi . The display of police violence, which resulted in 16 arrests, reignited outrage among young people across Georgian universities.

This discontent was widely echoed by academic staff at ISU and Tbilisi State University (TSU) — the latter being the largest public university, whose yard police special task units reportedly used to mobilise before dispersing the overnight protest gathering on the morning of 19 November.

‘My course is called “The History of Censorship Under Totalitarian Regimes”, and it is practically unfolding before our eyes,’ prominent literary critic Lasha Bughadze remarked while marching from ISU to TSU on Tuesday. This followed his outdoor lecture delivered on Chavchavadze Avenue, where both universities are located within less than ten minutes walking distance.

The 19 November crackdown triggered an around-the-clock sit-in of young activists at TSU demanding the resignation of the university’s rector, Jaba Samushia, but the violent dispersal of protests that day caused a larger wave that almost acted as a catalyst for academia to break its previously muted stance on election irregularities and the government’s draconian laws.

One of these laws, the so-called ‘Law on the Protection of Family Values and Minors’, commonly known as the LGBT ‘propaganda’ law, has been conspicuously avoided by most leading political and civil groups in Georgia, not just academia. However, it is widely understood to extend beyond its primary target — the country’s queer community — to pose a broader threat to civil society, including the media and academia, by imposing censorship and fostering isolation from the global scientific community.

[Read more: Explainer | What’s in Georgia’s new anti-queer bill?]

Part of a wider anti-queer legislative package set to take effect in December, the amendments would also ban universities from including content in their programmes that ‘promotes’ transgender identities or same-sex relationships.

‘This [law] would directly encroach on education and free speech, which should exist not just at universities but everywhere’, Keratishvili tells OC Media. ‘When you go after a university, you go after the entire country, because university is a place where people start raising their voices and express their opinions freely.’

‘We might end up deprived of an opportunity to study authors who discuss gender’.

The law will affect ‘everyone’ and ‘everything’, according to Nika Kereselidze.

‘The movies, the cinemas, the arts, music — anything you’ll try to do as art […] will be censored. We’re going to get Soviet Union censorship in a few years. Maybe not today but in a few years, we are going to be there’, Kereselidze warns.

By turning the initial two street lectures — held in response to election irregularities and state violence against dissenting youth — into an ongoing series, the Iliauni Student Movement ensured a platform for long-overdue discussions on censorship as well.

‘Any lecturer who leaves the auditorium will be welcomed by us outside’, the IliaUni Student Movement stated on 19 November, while announcing a walk-out for the next day. Indeed, their appeal for more scholars to step forward and deliver lectures outside the main university campus received an overwhelming response.

Speaking impromptu to students seated on yoga mats laid out on the pavements outside their main campus on 21 November, ISU anthropology professor Tamta Khalvashi took the opportunity to warn students about Hungary’s experience with democratic backsliding. This included its 2021 anti-queer law, introduced under the guise of protecting family values, and the harassment of the Central European University, which ultimately forced its relocation to Austria.

‘We are now facing precisely such a process. We are not merely opposing a specific political party but fighting against the very idea that restricts our academic freedom’, Khalvashi warned.

ISU, a hub of liberal thought and government critique, has already faced institutional threats from the authorities. Earlier this year, Georgia’s education authorities denied the university full accreditation — a development Khalvashi also highlighted to the students.

[Read more: Georgia’s Education Ministry withholds full accreditation from Ilia State University]

Ani Keratishvili described ISU as leading a somewhat isolated effort to draw attention to amendments to Georgia’s law on higher education, as part of a broader push to address the ongoing assault on freedoms in the country.

Much like the broader urban youth in Georgia, ISU’s students appear deeply concerned about their future and their role in a country veering toward an anti-democratic path. The contested elections, which briefly sparked cautious optimism in the lead-up to the vote, now seem to have left them unsettled and uneasy about what lies ahead.

In interviews, however, they rarely acknowledge emigration as an option for themselves.

‘If we imagine a very, very dystopian future, which I don’t even want to envision and don’t think about at all… no,’ Mshvenieradze interrupts her own train of thought when asked about it. ‘I am staying here to the end.’

Ani Keratishvili seemed similarly convicted regarding her intentions to remain in Georgia.

‘This is a very easy way out. If I leave today, then my coursemate leaves, and then my friends also leave; in 20 years, there will be no one left to ensure access to education in this country […] On the contrary, we must stand together and fight so that my peers who are contemplating leaving decide to stay, and those who have already left find their way back.’