Since Russia invaded Ukraine five months ago, the head of Georgia’s ruling party, Irakli Kobakhidze, has had a lot to say. OC Media counted the number of times the Georgian Dream chair had harsh words for Russia, and compared this to his criticism reserved for Ukraine and the West.

On 24 February, hours after Russian President Vladimir Putin announced a military invasion of Ukraine, Irakli Kobakhidze rushed to Facebook to express his solidarity with Ukrainians. While not explicitly mentioning Russia, a noticeable trend among Georgian officials under Georgian Dream party rule, his message was still clear:

‘The Ukrainian people did not deserve such injustice!!! Solidarity to Ukraine!!!’

Few doubted then that Kobakhidze referred to Russia as the perpetrator of such injustice. But in the weeks and months that followed, Georgian Dream’s leadership found themselves increasingly at odds with Ukrainian officials and their Western allies, even hinting occasionally that they brought Russia’s military aggression on themselves.

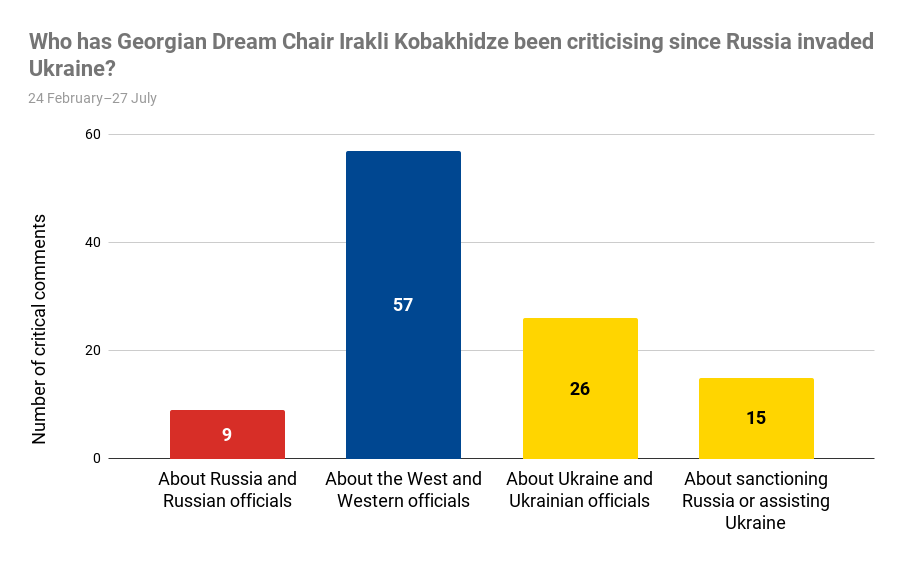

OC Media analysed statements by Kobakhidze made to or reported by the press from 24 February to 27 July, categorising them as being critical of Russia, critical of the West, critical of Ukraine, or against imposing sanctions against Russia or helping Ukraine in some other way.

What was found was that Kobakhidze has made comments critical of Russia, including implicit criticism of the invasion of Ukraine or aggression against Georgia, only nine times since the invasion.

By contrast, Kobakhidze has made comments criticising Ukraine and Ukrainian officials 26 times — just over once every six days on average.

By far the biggest target of his ire over the past five months, however, has been the West, with 57 critical comments.

The data was collected through Google searches for each of the 154 days since 24 February. Separate searches were conducted on pro-government outlet Imedi, and independent news agencies Interpressnews and On.ge to ensure the list was as comprehensive as possible.

Where a single statement or media engagement contained multiple criticisms of any one category, this was counted as one instance alone. Where Kobakhidze criticised multiple sides in one statement or media engagement, this was counted in each category.

Kobakhidze was chosen over, for example, Prime Minister Irakli Gharibashvili, due to his propensity to speak.

Criticism of Russia: one clear example (without mentioning Russia by name)

Throughout five months since the start of Russia’s military attack on Ukraine, OC Media registered only nine times Kobakhidze made statements portraying Russia in a negative light.

While almost all of those few statements referred to Russia negatively, this was rarely the primary focus of his statement. During the 22 weeks of Russia’s war, OC Media identified only one clearly worded statement in which Kobakhidze primarily focused on Russia’s aggression — his statement in solidarity with Ukraine at the outset of the war.

For instance, on 4 April, Kobakhidze did argue that Russia’s ‘military aggression’ against Ukraine had no justification (one of the nine statements counted). However, he did so while on damage-control following a seemingly vindictive anti-Ukrainian statement made by the prime minister a day earlier.

In another example, on 23 May, he mentioned Russia negatively, but only in order to allege that the previous government represented ‘9 years of Russian regime’ in Georgia.

OC Media included among Kobakhidze’s rare and technically ‘Russia-negative’ statements those that, when put in context, bordered on advocating for an appeasement policy towards Russia.

For instance, on 28 March, Kobakhidze briefly referred to Russia as an ‘occupying [military] force’ in Georgia but did so while contrasting his party’s ‘pragmatic’ policy towards Russia with Georgia refusing to join the Russia-dominated post-Soviet regional bloc, the CIS, in the past.

‘You remember, for example, how Georgia did not join the Commonwealth of Independent States [CIS], then how a civil war started, how we lost 80% of Abkhazia and half of Tskhinvali region [South Ossetia] within the following two years, and how we still ended up joining the CIS’, Kobakhidze continued.

Joining the CIS in 1993 was a very controversial decision domestically in Georgia. The country eventually left the CIS in 2009, after the August War.

[Read also on OC Media: Datablog | Who is pro-Russian in Georgia]

On Ukraine: a conspiracy and an intergovernmental feud

On 25 February, Georgian PM Irakli Gharibashvili announced Georgia ‘did not plan to participate in sanctions against Russia’ and described a suggestion to personally visit Ukraine as ‘fruitless’. Additionally, the ruling party blocked the convening of an extraordinary parliamentary session on Ukraine.

Several days later, reports emerged that the Georgian government had blocked a flight chartered by the Ukrainian Government to transport Georgian volunteers to Ukraine.

Ukrainian President Volodymyr Zelensky reciprocated by lambasting the Georgian government for their ‘immoral position’ and recalling their ambassador.

Since then, a spat between Georgian and Ukrainian authorities has escalated further, with Kobakhidze a key player in reacting to statements by Ukrainian officials. These included Oleksiy Danilov, Secretary of the National Security and Defense Council, President Zelensky’s advisor Mykhailo Podolyak, and Davit Arakhamia — an Abkhazia-born ethnic Georgian who leads the majority in the Ukrainian parliament.

‘Officials occupying the highest positions of power in Ukraine have openly started talking about opening a second front in Georgia and about the expediency of dragging the war currently ongoing in Ukraine to Georgia’, Kobakhidze alleged on 28 March. Prior to that, Danilov alleged that if Georgia and Moldova tried to ‘reclaim their territories’, it would have ‘helped Ukraine a lot’.

While Danilov’s suggestion was met with strong criticism both in Moldova and Georgia, a prospect of a ‘new’ or ‘second’ front of the war in Georgia has become a central element of a conspiracy theory pushed by the ruling party.

Since May, the conspiracy theory, spearheaded by Kobakhidze, has grown to include the opposition UNM, at least some Ukrainian officials, as well as figures in the US and the EU.

On 11 April, Kobakhidze demanded the Ukrainian government retract allegations against the Georgian government and dismiss former Georgian officials among their ranks if they wanted to see a Georgian delegation visiting Bucha, the site of Russian atrocities near Kyiv.

Several days later, with no further preconditions voiced by Georgian Dream, a Georgian parliamentary delegation did travel to Bucha and Irpin.

From Ukraine-critical to anti-Western

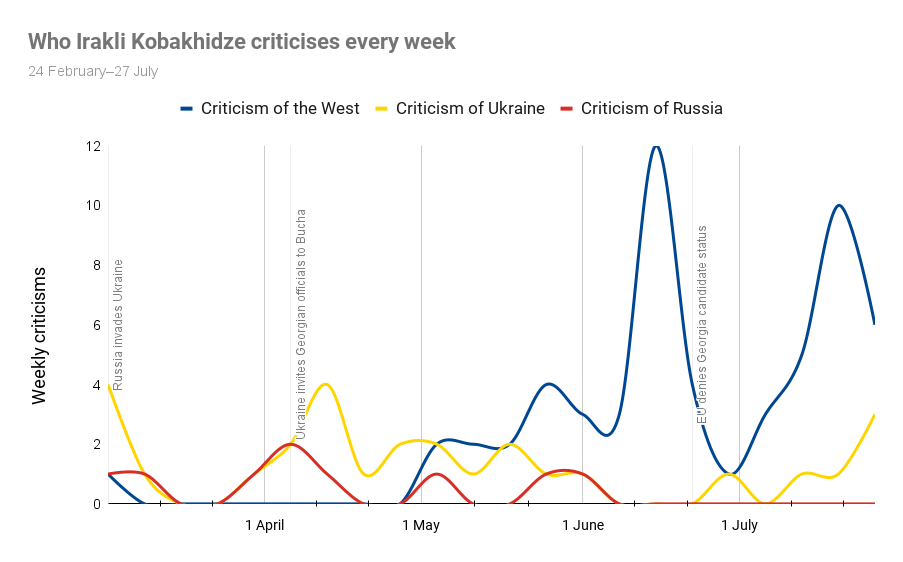

While Georgia’s relations with the West have been deteriorating for some time, especially since 2021, since the outbreak of the war, Eurosceptic and anti-Western rhetoric from Georgian Dream leaders has escalated further still.

Given the Georgians’ overwhelming support of their country’s pro-Western foreign policy, Irakli Kobakhidze’s wording in his criticism of the West is often obscure and full of dog-whistles, with specifics left to supporters to spell out.

However, along with the rising frequency in his statements slamming various actors of the West, Kobakhidze’s conspiracy theory about an alleged plot to involve Georgia in the war has also crystallised more.

For instance, on 10 May, he warned that his team was ‘seeing some coordination’ in pushing their former leader and ex-PM Bidzina Ivanishvili to ‘return to politics’ and make him ‘involve Georgia in war’ with Russia.

While he did not specify who was doing the pushing at the time, the statement was largely understood by both Georgian Dream supporters and opponents (including the media outlets affiliated with both) as being aimed at the USA and its embassy in Georgia.

By July, Kobakhidze made clear that he had questions about the alleged conspiracy for US Ambassador to Georgia Kelly Degnan, whom he later also accused of pressuring a Georgian judge for a politically controversial ruling.

[Read more on OC Media: US State Department condemns Georgia’s ‘personal attacks’ on their ambassador]

Overall, since Russia’s invasion of Ukraine, OC Media registered 57 times the chair of the ruling party in Georgia publicly criticised the West, be it western ambassadors, members of the European Parliament, or EU institutions.

Those 57 also included Kobakhidze’s public messages with at least a Eurosceptic tone.

For instance, on 1 March, Kobakhidze called a suggestion that Georgia applied for EU membership together with Ukraine a ‘fuss over nothing’, only to announce the opposite within the following 24 hours.

And again, following a critical resolution by the European Parliament that signalled a looming rejection of Georgia’s application for membership, Kobakhize suggested the government could have been duped into applying in order to fail. He also downplayed the ‘practicality’ of candidate status.

Despite this, in early June, Georgian Dream continued to insist they were committed to securing candidacy later that month. The declared mission, however, contrasted with Kobakhidze’s statements that threatened the EU with a ‘grave reaction’ if they treated Georgia unfairly. He also did not hesitate to call ‘Europeans’ supporters of ‘criminals’, referring to the former ruling party.

After the EU did not grant Georgia candidate status while giving it to Moldova and Ukraine, Kobakhidze alleged Georgia was discriminated against for not waging war with Russia.

‘God forbid, but if we theoretically allowed that war to erupt in Georgia by the end of December, of course, in that case we would have candidacy status guaranteed. However, perhaps […] it’s not worth attaining such status this way’, Kobakhidze told the public broadcaster on 5 July.

In addition to alleging that US Ambassador Kelly Degnan was pushing Georgia to war with Russia, on 20 July, the outgoing EU Ambassador to Georgia Carl Hartzel also found himself among those being accused of complicity in Georgia’s EU failure.

‘Carl Hartzel played only a negative role in EU-Georgia relations. This is very unfortunate’, Irakli Kobakhize bemoaned on 20 July.

Leaving Georgia ‘isolated and without friends’

In conversation with OC Media, Natalie Sabanadze, who served as Georgian Ambassador to the EU for eight years, called the kind of rhetoric employed by Kobakhidze and others ‘unprecedented’.

She said that Georgian Dream had traditionally pursued a ‘more reconciliatory approach to Russia than their predecessors’, but questioned the results of this proclaimed ‘pragmatism’.

‘Whether it is pragmatic or not, the answer lies in the latest developments in Abkhazia; I mean around Pitsunda’, she noted.

She said that while such a ‘Russia-soft approach’ was not new, this was now being combined with ‘talking tough to Western partners’.

‘It is a real irony that the most Euro-enthusiastic country such as Georgia ended up with a Eurosceptical government in disguise’, Sabanadze said.

Sabanadze was pessimistic that the government would change course in this regard.

She said that implementing the reforms demanded by the EU for the country’s candidacy to be reconsidered would ‘go against the very nature of the regime that the Georgian Dream has built’ and would even be ‘self-destructive’ for them.

She said that the government would likely still attempt to convince the public they were pursuing the reforms which would ‘continue to be accompanied by anti-Western propaganda’.

‘The objective now is to actually decrease popular support for the EU and NATO in Georgia. It is this support precisely that increases political costs for Georgian Dream for its inaction. So they are telling the public that we are facing a choice: peace vs the EU’, Sabanadze said.

‘It is a highly effective approach for party political purposes and utterly disastrous for the interests of the country’, she said. ‘It is leaving Georgia increasingly isolated, without friends to rely on and alone face to face with an occupying power.’

‘This not only risks our European future, but it also undermines Georgia’s hard-fought independence.’