The situation on Armenia’s labour market is dire and it’s women who are affected the most. Gayane Ghambaryan, who has worked most of her life doing ‘man’s work’, tells of her struggle as her family’s sole breadwinner.

The situation on Armenia’s labour market is dire and it’s women who are affected the most. Gayane Ghambaryan, who has worked most of her life doing ‘man’s work’, tells of her struggle as her family’s sole breadwinner.

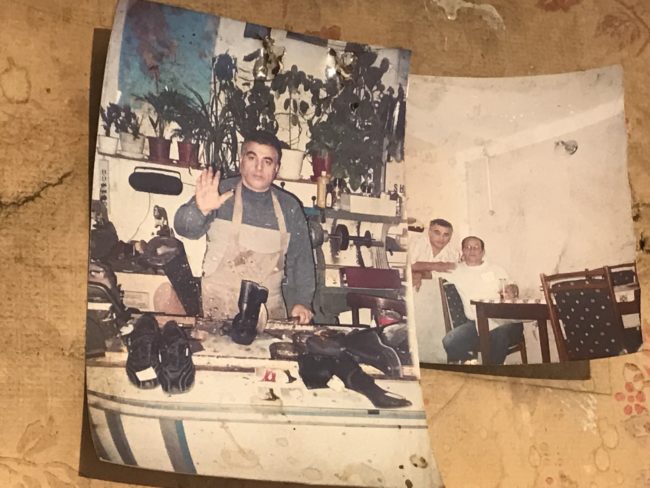

Gayane Ghambaryan, who is known in Yerevan as the woman shoemaker, has spent 25 years of her life in a dilapidated cottage with a roof destroyed by rain and snow and the scent of glue deeply soaked into the walls.

At her small workshop on the outskirts of the city, she always greets her visitors with a kind smile, hiding the tiredness in her eyes.

‘I was 17 when I married. My husband was the head of a shoe workshop, a good designer, a wealthy man, who promised that I would definitely get a higher education, would live without any needs’, Gayane began her story.

Gayane didn’t manage to receive an education, her dream has not come true. It was a typical story for many Soviet families. The eldest member of the family forbade his daughter-in-law to pursue a higher education, noting that her work was to care for children and to be a housewife.

‘The situation has changed over the past few years, but to be a woman is still hard in Armenia’, Gayane said, picking another shoe up. ‘Do not look at my deformed fingers. I used to have nice hands when I was young and when I was doing “women’s work”’, she added.

‘At the beginning of the 1990s, when life was very hard, I used to cook biscuits at home and we sold them. My husband noticed that I did it well and he asked me to help him in the workshop’, Gayane explains.

Gayane began to work at the workshop temporarily, being sure that soon she and her husband would be able to start their own small workshop, where she would work as a bookkeeper. Unfortunately, it turned out that it was only a dream.

‘I had to take a hammer and a packing needle in my hands and do a man’s work. My husband died when I was 50 leaving me alone, and it is very hard to find work in Armenia’, she recalls with sadness. She searched for ‘woman’s work’ for a long time, but couldn’t find anything.

According to the data of Armenia’s National Statistical Service, 226,600 people are currently looking for work in Armenia, of which 54% are women.

‘I have three children and five grandchildren. I take care of my 36-year-old daughter and my 10-year-old grandson. We live in a rented flat. My daughter has no job. She was looking for work, but couldn’t find any. She was told that she was not young enough for a job. Today, even to be a cleaner in Armenia, you must be young and have perfect looks. If you do not meet these criteria, you are condemned to unemployment’, Gayane said.

During all our conversation, Gayane was mending shoes, adding that she had to hurry to finish her work, otherwise the three members of her family would go hungry.

‘There are days when I don’t earn anything. There are days when I earn as little as ֏300 ($0.62). There are also happy days when I can earn about ֏8,000 ($16), but such days are very rare. I do not receive pension yet, so we survive on my salary [women receive pension from the age of 63 in Armenia]. The problem is that we will be deprived of my work soon, as I am in poor health and I am not able to work anymore’, Gayane said pointing at her deformed middle finger. She joked that her hand grew a sixth finger.

‘My hand bothers me a lot. Now, I am doing my work instinctively, I strike the hammer automatically, but I am not able to wash a coffee cup at home. I am practically physically disabled’, Gayane said.

In her workshop, there is a small cupboard with coffee sets. Gayane never complains of a lack of guests, who often visit her for a cup of coffee. A group of unemployed women often gathers at her workshop. They say they have nothing else to do.

OxYGgen, a women and youth focused development organisation, has examined economic gender inequality in the country. According to them, women searching for jobs in Armenia must spend much more time to find one than men. Over the last four years, 60% of women have sought work, compared to 39% of men.

According OxYGgen, 32% of Armenian women are registered as business owners in the state register, but in reality, only 13% of them are the real owners. The rest are fronts for their husbands or relatives, who are usually state employees and are trying to hide their wealth.

Unemployment affects women in Armenia more than men. Men also enjoy much higher salaries.

For example, according to the Gender Investigation and Leadership Centre at the Yerevan State University, 62% of men and 56% of women polled believe that when there is a shortage of jobs, priority must be given to men.

According to national statistical data, six years ago, the median monthly salary for men was ֏125,000 ($257), which has now grown to ֏190,000 ($390). For the same period of time, the median monthly salary for women has gone from ֏75,000 ($154) to ֏125,000 ($257).

‘My male colleagues can charge ֏1,000 ($2) to mend a shoe pedestal, while I take ֏500 ($1). I do nonprofit work’, Gayane said with resignation.

She places her hopes in her grandchild, Narek, whose paintings and crafts decorate her workshop.

‘Narek dreams to be an economist. He is a clever boy. I am sure his dream will come true and soon he will be our breadwinner. The leader of our family will be a man’, the shoemaker adds with hope.