‘I write in encroaching darkness, about the darkness that is falling across my country, Georgia’, Mzia Amaghlobeli wrote in a letter from prison to The Guardian. She is the first female journalist to be jailed in Georgia for politically motivated reasons since the country’s independence in 1991. In recent months, her health and vision have deteriorated alarmingly.

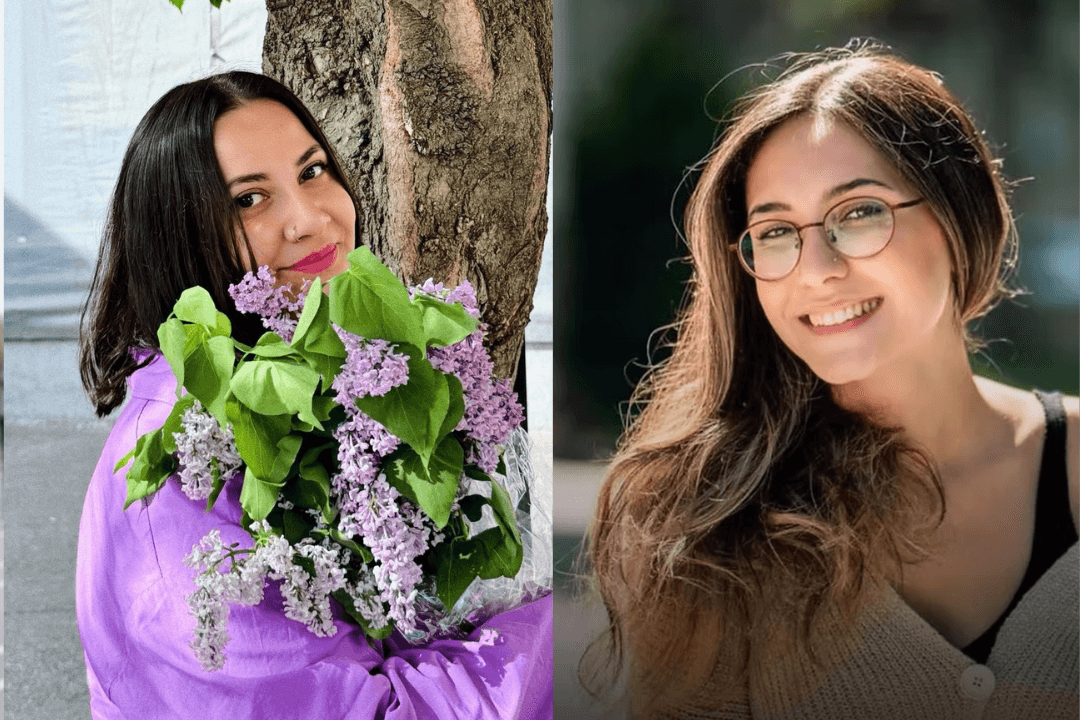

Her case reflects a wider trend: the rollback of rights and freedoms in Georgia. To explore these developments, OC Media spoke with human rights lawyer Tamar Dekanosidze, the Eurasia Regional Representative at Equality Now, an organisation working to end violence and discrimination against women and girls in Eurasia and around the world.

As Georgia continues to backslide on its commitments to both the EU and the UN Sustainable Development Goals (SDGs) — particularly SDG5 on gender equality — Dekanosidze discusses the chilling effects of newly enacted legislation, from the controversial foreign agent law to the erasure of the word ‘gender’ from national law.

OC: How do you assess the detention and trial of journalist Mzia Amaghlobeli?

Dekanosidze: Mzia Amaghlobeli’s case is a stark illustration of the erosion of civic space in Georgia and the repressive measures increasingly used to silence critical voices. Her detention — on disproportionate criminal charges for allegedly slapping a police officer during a protest — reflects how the criminal justice system is being instrumentalised not to uphold justice and equality, but instead, to suppress journalists, activists, human rights defenders, and opposition figures who challenge the government’s policies.

Amaghlobeli’s pre-trial detention, given her health and the nature of the act she’s charged with, is excessive and punitive. The Georgian Young Lawyers Association (GYLA) has taken the case to the European Court of Human Rights (ECHR), which has already started examining the matter, illustrating its urgency and serious nature.

Her case also has a clear gender dimension. Amaghlobeli is facing harsh consequences for a single act that reportedly caused no physical harm, yet in a country where one in four women has experienced physical or sexual violence, violence by men often goes unpunished. The stark contrast in how justice is applied reveals a deep systemic bias and reflects broader patterns of state repression, particularly against women who speak out or take part in civic and political life.

What impact have the recent developments had on civil society in Georgia?

The space for civil society has been shrinking at an alarming rate. In 2024, parliament passed the law ‘On Transparency of Foreign Influence’, which, while presented as a transparency measure, actually targets civil society organisations, including those working on women’s rights, violence against women, and broader human rights issues. The law imposes burdensome registration and reporting obligations on groups that receive foreign funding.

Then, in April 2025, parliament adopted the ‘Foreign Agents Registration Act’, which goes even further. It requires individuals and organisations that receive foreign funding and advocate on policy matters to register as foreign agents. The act subjects them to government surveillance and introduces criminal penalties for non-compliance, including imprisonment. Even the awarding of grants to civil society groups now requires government approval, with harsh sanctions for non-compliance.

In the past years, Georgia was seen as making steady progress on human rights and gender equality. What has changed since 2024?

Unfortunately, we have witnessed a significant regression in human rights protections in Georgia since 2024, including in the areas of women’s rights and gender equality. This includes the abolition of mandatory gender quotas in the Election Code in May 2024. These quotas had required political parties to include women on their party lists for parliamentary and municipal elections — a crucial mechanism to promote women’s political participation.

The situation further deteriorated in March 2025, when, among other regressive policy measures, the Permanent Parliamentary Council for Gender Equality was abolished. Just a month later, on 2 April, parliament amended over a dozen laws to remove all references to ‘gender’ and ‘gender identity’, signalling a clear departure from equality-based policymaking.

What are the implications of removing the term ‘gender’ from Georgian legislation?

Removing the word ‘gender’ is not just symbolic — it has concrete and harmful effects. It reflects a broader shift toward anti-equality politics and deprioritisation of the issue of violence against women, and hinders decades of progress toward ensuring that women’s rights and protections are built into law.

Gender-based violence, for example, is rooted in systemic inequality and harmful stereotypes about women. Eliminating the legal language that acknowledges this makes it harder to ensure effective criminal justice responses, including making it harder to hold perpetrators accountable for the act they committed.

Removing ‘gender’ contradicts the Council of Europe’s Istanbul Convention that Georgia is party to. It is also at odds with the case-law of the ECHR in relation to Georgia (such as A. and B. v. Georgia, Theklidze v. Georgia, and Gaidukevich v. Georgia), which specifically underline the gendered nature of violence against women. And it erases recognition of the structural discrimination women face simply because they are women in a patriarchal society.

These changes seem to be part of a broader trend. Can you tell us more about other legal developments during this period?

Yes, this trend didn’t emerge in isolation. It was preceded by the adoption of the so-called law ‘On Protection of Family Values and Rights of Minors’ in December 2024. That law deeply undermines the rights of queer individuals. It effectively prohibits any representation of queer issues in education, media, and public spaces and severely restricts transgender people’s rights to gender identity recognition and access to healthcare, even introducing criminal penalties in some cases. The subsequent removal of ‘gender identity’ from national legislation further entrenches discrimination against transgender, non-binary, and gender-nonconforming individuals.

What are some of the discriminatory laws currently in place in Georgia?

There are quite a few discriminatory laws in Georgia, especially in light of recent legal changes that have rolled back protections for women and marginalised groups, as we’ve discussed.

One of the most persistent and concerning examples of laws that put women at a disadvantage is the absence of a consent-based definition of rape in the Georgian Criminal Code. This remains a major gap, despite being a requirement under multiple international criminal law and human rights instruments that Georgia is party to, including the Istanbul Convention, European Court case-law, and recommendations from the Committee on the Elimination of Discrimination against Women (CEDAW) and the Universal Periodic Review (a UN Human Rights Council mechanism where all UN member states are peer-reviewed on their human rights records every 4.5 years).

It’s important to note that several countries in the region with shared legal traditions, such as Moldova, Ukraine, and Armenia, have already adopted consent-based definitions of rape. Georgia, however, still requires proof of physical force, threats, or helplessness, which excludes many situations where the act was committed without voluntary and free consent. This not only limits access to justice for survivors but also perpetuates outdated and harmful assumptions about sexual violence and women in general.

How do recent legal changes in Georgia relate to its commitments under the UN Sustainable Development Goal 5, and how does Georgia compare to other countries of the region?

While Georgia currently ranks 59th out of 167 countries in overall SDG progress, it still has a long way to go, including on SDG5. The abolition of mandatory gender quotas, which had helped increase women’s political participation, is especially concerning, as this is a key SDG5 target.

In comparison, Armenia, which ranks 50th in overall SDG progress, has taken more proactive steps to advance women’s participation and inclusion — it now leads the region in SDG5 progress. In turn, Azerbaijan ranks 64th and has shown limited or minimal progress in areas such as family planning, education, labour participation, and political representation for women.

Georgia has made important strides in recent years toward achieving the Sustainable Development Goals, including SDG5 on gender equality. However, the recent rollback of gender quotas, the removal of gender from legislation, the deprioritisation of government efforts to address violence against women, and the weakening of institutional mechanisms for equality directly undermine these commitments.

Yet, with renewed commitment and the right policy choices, Georgia has the potential to reverse these setbacks and once again position itself well for advancing gender equality and the Sustainable Development Goals.

____________________________________________________________________________________

With over 15 years of experience, Tamar Dekanosidze is a human rights lawyer from Georgia and is Equality Now’s Eurasia Regional Representative. Tamar has worked on legal and systemic reforms to address gender-based violence and discrimination, trained professionals, engaged with human rights mechanisms, and has represented survivors of gender-based violence and other human rights violations in local, regional, and international courts and bodies (such as in the ECHR and CEDAW), securing outcomes that provided access to remedies for survivors and led to broader legal and policy changes.