Opinion | Georgia’s ‘democratic’ institutions are reinforcing autocracy

Georgia’s authoritarian regime uses democratic-seeming institutions to maintain its hold on power and so complicate efforts to resist, as seen recently with their use of the Anti-Corruption Bureau to crack down on election observers.

Georgia’s authoritarian regime, constructed by billionaire ruling party founder Bidzina Ivanishvili, is a prime case of how democratic institutions can deteriorate, becoming mere facades of democracy while fully enabling the repressive machinery of authoritarianism.

Such regimes strive to maintain a democratic appearance in the eyes of both domestic and international observers, and so complicate efforts to resist them. As the Georgian example demonstrates, such regimes reveal their true nature only when no alternative remains. Until then, they diligently construct an autocratic framework behind the guise of democracy, creating an environment where institutions are progressively subjugated and human rights are systematically eroded and ultimately eliminated.

Maintaining a facade of democracy enables modern authoritarian regimes to create the illusion that the responsibility for poor decisions lies with the institutions delivering those decisions. However, these institutions lack genuine authority to check and balance other manifestations of state power, with true power remaining firmly outside these institutions, in the hands of the authoritarian leader. Despite their stated aims, such institutions serve merely to support authoritarian repression and the preservation of power.

Nonetheless, the illusion feeds hope that the institutions might still serve as tools for democratic resistance; hopes that reliably end in disappointment.

In Georgian reality, there are countless examples of disappointment stemming from the actions of such institutions.

One such example relates to Georgia’s Constitutional Court. While Georgia’s president, a number of MPs, media, and civil society organisations took a challenge to the foreign agent law to the court in August, requesting its suspension, on 9 October the court refused the request, with no justification or substantial reasoning.

An even more flagrant example is the state’s establishment of the Anti-Corruption Bureau in November 2022.

The body was created in response to EU recommendations relating to Georgia’s bid for EU membership, and the Bureau’s website pays lip service correspondingly. Its ‘About Us’ section focuses on Georgia’s ‘firm will’ to become a member of the European Union, as stated in the constitution, and the Bureau’s role in the path towards that; enacting the 12 recommendations from the European Commission, the fourth of which calls for strengthening anti-corruption mechanisms.

Given the Georgian public’s overwhelming public support for European integration, the government had to at least appear to implement some of the recommendations, particularly to appeal to the pro-European voter base.

And while the Bureau’s creation was welcomed by many, the specifics of its implementation were widely criticised. In particular, the decision that the Prime Minister should appoint the Bureau’s head went against Georgian civil society’s demands that the head be elected by Parliament to ensure their independence.

On top of this, while the Bureau’s founding involved consolidating previously scattered anti-corruption mechanisms from various agencies into a single entity, the new body had the mandate of not only promoting the fight against corruption, but also monitoring the financial activities of political parties, electoral subjects, and individuals with declared electoral objectives.

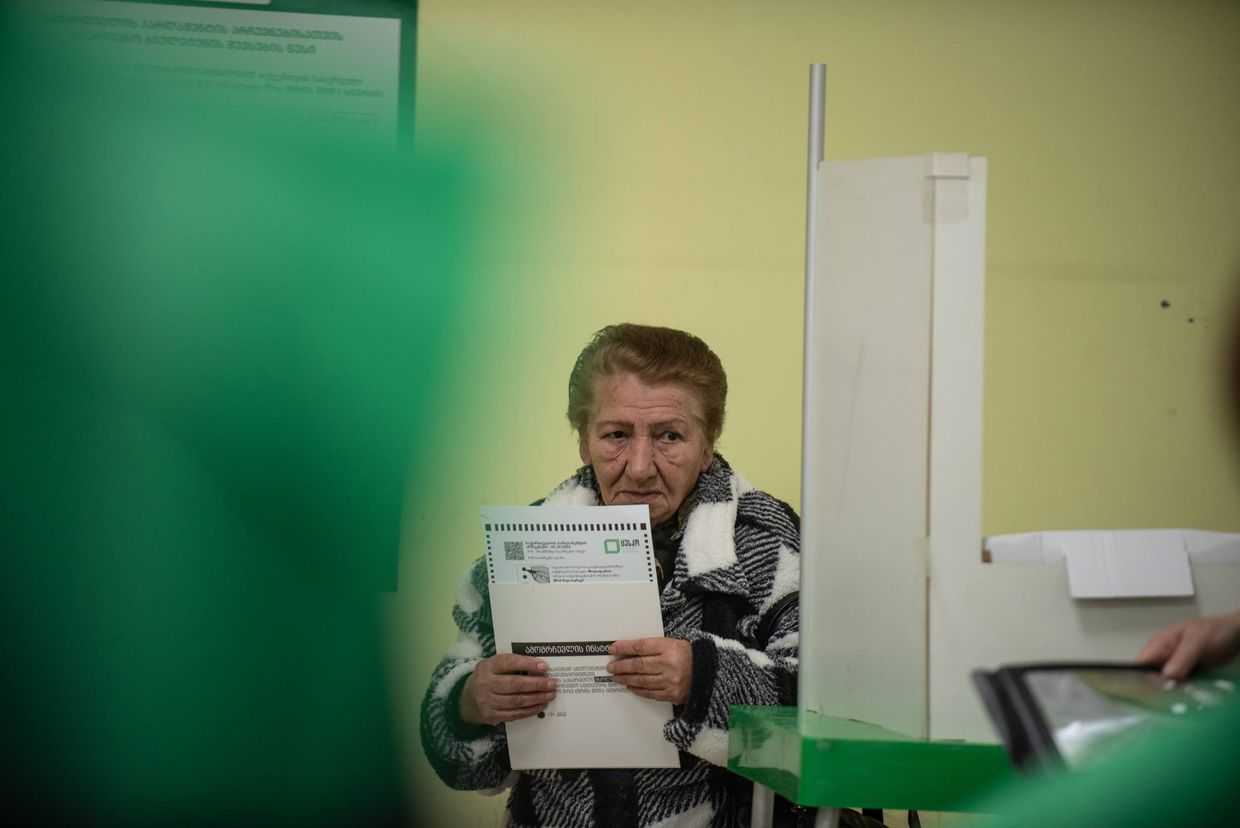

That broad remit has been used to target non-governmental organisations in the run-up to the 26 October parliamentary elections.

On 24 September, the Bureau’s head, Razhden Kuprashvili, designated the civil society organisations Vote for Europe and Transparency International — Georgia and their leaders ‘subjects with a declared electoral goal’. In effect, this categorised the organisations as political parties, subjecting them to the corresponding financial and operational restrictions.

It is unclear whose cunning mind conceived such a decision, but it is disastrous for any non-governmental organisation, particularly one that monitors elections. Designating a key election monitoring watchdog as having ‘a declared electoral goal’ disables the organisation, preventing it from fulfilling its duties in an election set to be contentious even by Georgian standards.

This amounts to a substitution of the non-profit organisation’s mission for a political one. For a neutral monitoring organisation, rigid adherence to a biased, political goal renders its election observation meaningless.

Somewhat unexpectedly, the decision was retracted — perhaps deemed too controversial prior to the elections — but the retraction itself appeared to confirm the Bureau’s subservience to the ruling party. On 1 October, Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze publicly called on the Bureau’s head to revoke the decision, and Kuprashvili did so with no protest a day later.

In such a way, an agency created under the pretext of bolstering democracy has been transformed into a cornerstone of autocracy in Georgia.

As the government further dismantles state institutions from the inside and captures the legislature, it is clear that Georgia is at a critical juncture. If the ruling Georgian Dream party retains its hold on power, all state institutions are likely to rapidly become agents of government oppression: ruling party-serving appointments of judicial officials and threats against education and cultural institutions are likely to only intensify.