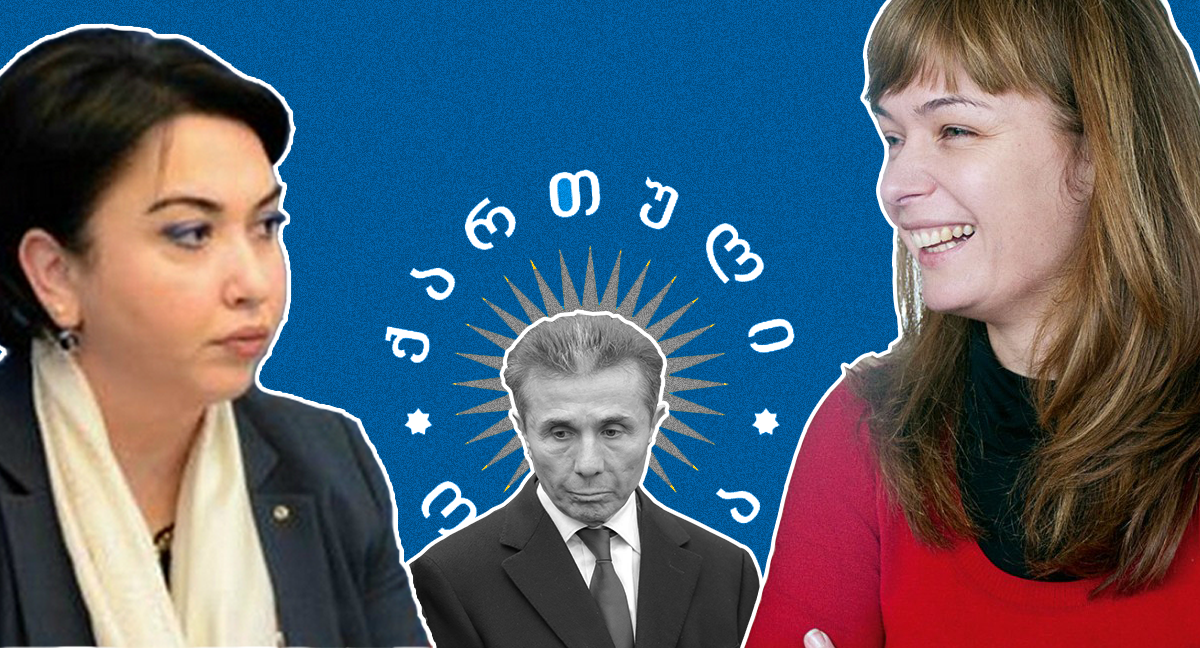

Opinion | Ivanishvili clings to a frayed political brand while facing a new kind of opposition

On the eve of the 19 May by-elections in eight municipalities and for a parliamentary seat in Tbilisi’s Mtatsminda District, the Georgian Dream party, chaired by Georgia’s informal ruler Bidzina Ivanishvili, faces a potential new rival that could potentially mobilise the party’s estranged base — the Tbilisi elite.

On 13 April, several thousand gathered in Tbilisi’s main concert hall for the announced revival of Defend Georgia. The group comprises of some of Tbilisi’s most influential public figures, who helped Ivanishvili oust the United National Movement (UNM) from power in the 2012 parliamentary elections.

While there is little evidence to suggest that Defend Georgia aspires to form a political party, the gathering sent a strong signal to the government that they should not expect unconditional support during the by-elections this May, or, more importantly, during the 2020 parliamentary race.

The meeting, which called on the public to remove Georgian Dream from government ‘without enabling the UNM to make their comeback’, happened five days after Ivanishvili penned his latest appeal to the public.

In his written address on 9 April, the 30th anniversary of a violent dispersal of anti-Soviet demonstrators in Tbilisi, Ivanishvili called for ‘national unity’. However, the address mostly reflected the challenges his own party is facing today.

The ‘unity’

As Georgia recovers from the hangover of political polarisation, which peaked during the presidential elections last autumn, a focus on internal political cleavages is something to be welcomed.

But by castigating the ‘forces longing for chaos’ who are ‘thinking about revenge’ — apparent references to parliamentary opposition groups the UNM and their spin-off, the European Georgian party — Ivanishvili made clear that his intention was anything but to stop divisiveness within party lines.

What Ivanishvili is fighting for is the soul of his party in its original form: a political brand positioning them as an alternative to former president Mikheil Saakashvili’s rule and to his hypothetical comeback.

Hence, the actual target group of Ivanishvili’s call for a vague ‘national unity’ was his former allies among the Tbilisi elite, a network of influential public figures that could theoretically contribute to Georgian Dream’s ultimate electoral win — or loss.

‘We should stop dividing society under a slogan of fidelity to principles… [stop] constantly reminding each other of the political past’, Ivanishvili’s statement read, making it clear what was on his mind.

Since winning a constitutional majority in the 2016 elections, Georgian Dream has suffered the loss of eight MPs. Additionally, several that have stayed in the party are openly disrespecting Speaker Irakli Kobakhidze, Ivanishvili’s right-hand man in parliament.

Almost all of them are claiming that Georgian Dream is failing to remain true to its original mission of undoing injustices committed during Saakashvili’s rule.

Allying with corrupt judges

Most of the MPs that departed the ruling party did so over the issue of lifetime appointments of justices to the Supreme Court.

The planned appointments, a part of the justice system reforms that previously garnered less public attention, have now become a major political issue in Georgia.

In late 2018, Georgian Dream decided to go forward with the lifetime appointments of controversial justices strongly represented within the High Council of Justice (HCoJ), an independent agency responsible for overseeing the Georgian courts.

The HCoJ is run by an influential group of judges responsible for a number of controversial, high profile rulings during the Saakashvili era. This prompted most of the MPs that left Georgian Dream within the last couple of months to accuse their party of unacceptable cooperation with corrupt judges.

Gathered around MP Eka Beselia, one of the original founders of Georgian Dream, departed ex-Dreamers claimed that retaining ‘corrupt judges’ who delivered political rulings in the past was a ‘red line’ for them.

They also made sure to be present at the Defend Georgia event on 13 April as special guests.

Georgian Dream is used to being accused of corruption, mismanaging the economy, and compromising Georgia’s integrity with regards to Russia. They always use the same messages to counter these claims from opposition groups.

What the ruling party cannot afford, however, is to be blamed for allying with a group responsible for systemic injustices committed under the watch of their main nemesis, Saakashvili.

Ivanishvili, in allying with the ‘clan of judges’ widely believed to have been compliant to Justice Ministry during Saakashvili’s presidency, has directly jeopardised his credibility in being able to ‘restore justice’.

Beselia and most of the others that left Georgian Dream in February have failed so far to convince a public disappointed with the planned justice appointments that they have become Ivanishvili’s genuine rivals. So far their message has been that Ivanishvili’s party is out of touch, sparing the party chair of any harsh criticism.

Nevertheless, the 13 April gathering in Tbilisi suggests that Georgian Dream has become even more vulnerable. The groups making up Defend Georgia, which are not overtly pro-Russian (like Alliance of Patriots) or a part of the extreme right (like Georgian March), now claim that Georgian Dream should be unseated, though they do not want Saakashvili to make a comeback.

Out of ideas

At the end of March, Ivanishvili advocated for an investigation into the death of the first Georgian president, Zviad Gamsakhurdia. He also paid a visit to Samegrelo Region, where the former president is traditionally venerated. He vowed to set up a museum in his honour and also to spend ‘more than ₾1 million [$370,000]’ to restore an orthodox church in Zugdidi.

All of these efforts suggest that Ivanishvili takes the mayoral by-elections in Zugdidi, planned for 19 May, very seriously, especially as Georgian Dream would not want to see the UNM’s chosen candidate of Sandra Roelofs, the spouse of Saakashvili, gaining a symbolic win in the region.

Nevertheless, these short-term goals in which Ivanishvili is expected to be financially generous will not solve his problem in the capital.

In his address on 9 April, Ivanishvili reiterated for the third time after his official comeback to politics a year ago that while Georgian Dream has safeguarded political freedoms in Georgia, the economy is still lagging behind.

In the absence of a strong political party channelling Georgians’ economic grievances, the perceived tolerance to abuses of power could easily end in a change of power.

The opinions expressed in this article are author’s alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of OC Media’s editorial board.