Opinion | Political grandstanding won’t bring peace — introspection might

The 8 August agreements, though incomplete, could become an entry point to a more inclusive peace if all actors commit to collaborating toward it.

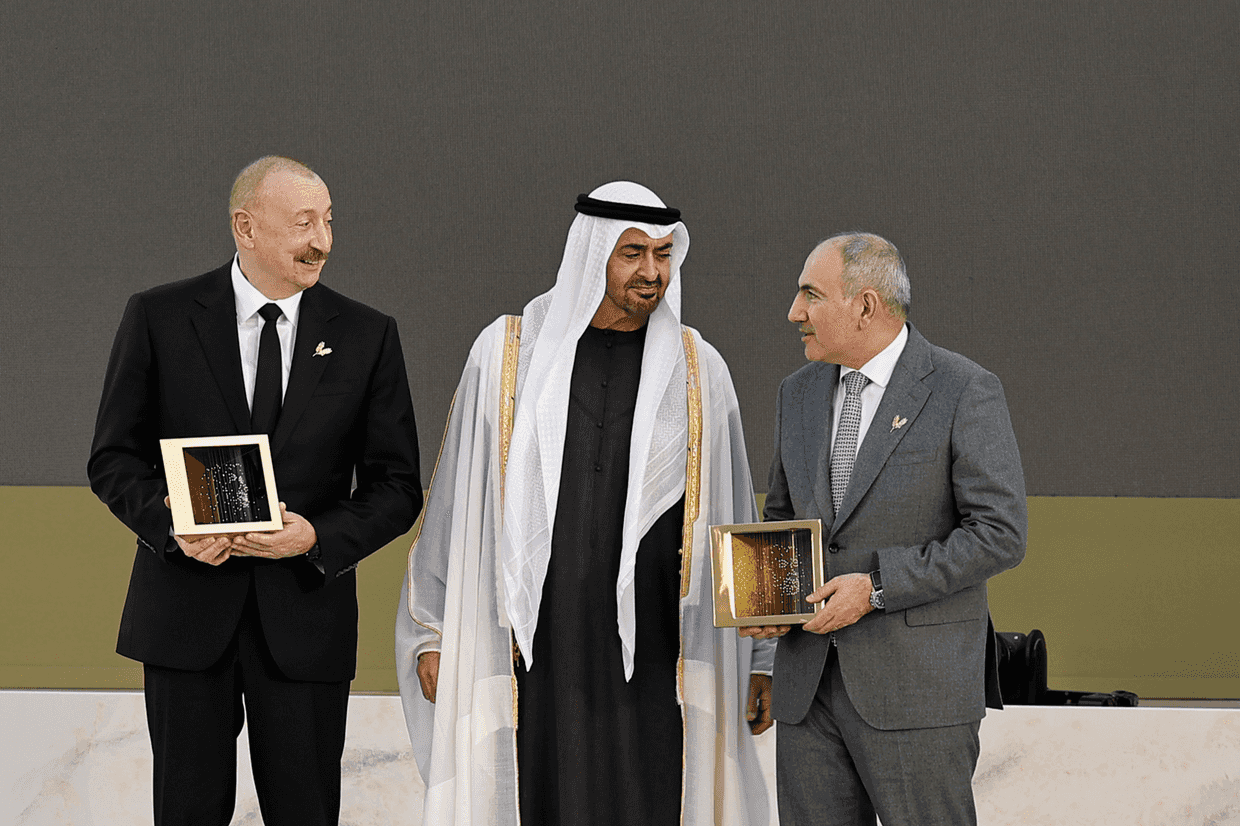

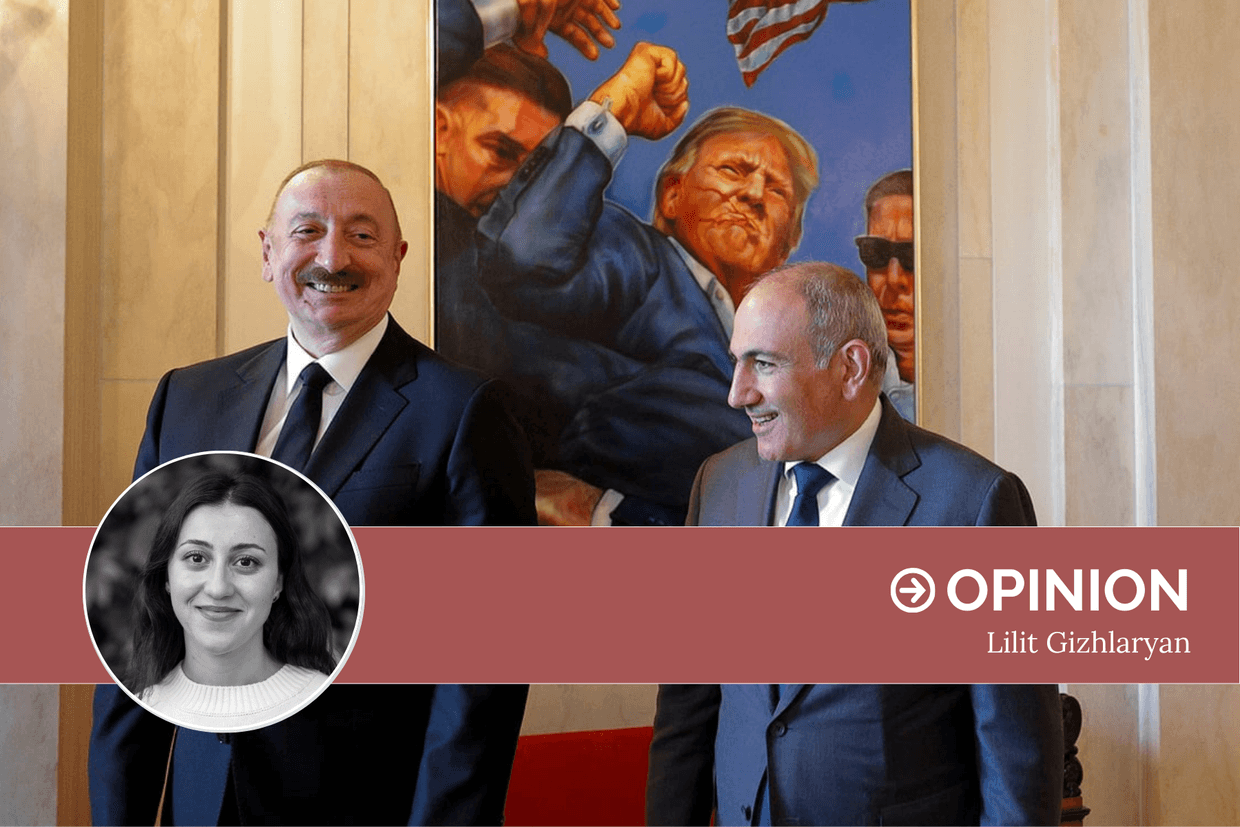

The summit in Washington on 8 August, when the Armenian and Azerbaijani leaders signed an agreement committing to end their decades-old conflict under the auspices of US President Donald Trump, continues to reverberate in Armenia’s political and social life.

Despite Trump’s assurances that Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan and Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev ‘will have a great relationship’, both leaders and their societies face a long road to establishing non-hostile relations. Locally, political parties and analysts, depending on whether their ideology is more pro-West or pro-East (in this case, rather pro-North), perpetuate narratives that frame the agreement as either a danger or a salvation for Armenia at this delicate historical moment. Less vocal, however, are the voices that try to make sense of the declarations and wait to see how reality unfolds over time.

Some statements reflect legitimate concerns about the peace process, while others remain trapped in historical grievances, stereotypes, and animosity. Some of these views are helpful to a constructive debate, while others risk perpetuating a fatalistic cycle that casts Armenia solely as a victim, stripping it of agency.

Domestic divisions: politicising the discourse

Shortly after the Washington summit, Armenia’s parliamentary opposition labelled the agreement a ‘new existential threat’ and a ‘capitulation’ by the government, insisting that it has nothing to do with real peace.

The opposition describes it as yet another act of continuous surrender, claiming that the concessions offered by Armenia only encourage Aliyev to advance further, allowing Azerbaijan to take destructive actions against Armenia and the peace process.

Others stress the painful questions left unanswered by the agreement, viewing it as the legitimisation of the ethnic cleansing of Nagorno-Karabakh’s Armenians, the detention of Armenian civilians, military officers, and political leaders in Baku, the erasure of the Armenian presence in Nagorno-Karabakh, and the approximately 200 square kilometres that Armenia claims Azerbaijan occupies inside Armenia proper. In their view, peace is neither comprehensive nor inclusive; for Armenians it represents a threat, while for Azerbaijan it serves as encouragement to continue crimes against Armenia and Armenians. In a nutshell, the documents cannot guarantee stable, just, or dignified peace because they are ‘written in the blood and rights’ of Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians.

Pashinyan’s critics warn that the ruling party may use the agreement to claim political victories ahead of the June 2026 elections. He and his party have already announced that, since Washington, Armenia’s investment and economic ratings have improved, suggesting the agreement carries some tangible effects. Others in the opposition have labelled the declaration ‘shameful’, accusing the country’s leaders of handing Armenia away piece by piece. The absence of specific maps that would ensure Armenia’s territorial integrity is another critique of those who are sceptical that the agreement is viable.

It would be naive to ignore these concerns or to claim that the peace process is not fragile. My aim is not to suggest that the Washington declarations or the ongoing negotiations with Azerbaijan are straightforward; they are delicate and complex, leaving many issues unresolved. Azerbaijan has yet to sign the agreement, and its rhetoric toward Armenians remains hostile. It continues to use language that Armenia opposes, such as the term ‘Zangezur corridor’, and is still pressuring Armenia to amend its constitution as a precondition for signing, making it even harder for Armenian society to trust the process.

The agreement has also added complexity to Armenia’s regional foreign policy, particularly in its relations with Russia and Iran. However, while the commitments do not answer all these questions, nor do they guarantee comprehensive, inclusive, and lasting peace, they can be seen as an opening toward negotiations for such peace, which will be a rough road but better than no road at all.

What steps should be taken?

For better or worse, the state cannot work alone to achieve the holistic peace desired for the region, nor is it possible to accomplish in a short time. The state, civil society, educational institutions, and the wider public must each play their roles, setting realistic goals and working to achieve them. This requires creative and critical thinking to break the patterns of constant mistrust, bloodshed, and displacement that have dominated the region in the last centuries.

Breaking cycles is painful, yet possible. Change is difficult as it requires both sides to ‘enter the dance’ of trust building step by step, breaking destructive patterns of the past. If Armenia or Azerbaijan wait for the ‘perfect time’, that time will never come. Armenia now has the hard task to convince Azerbaijan that peace is mutually beneficial.

On the government’s end, there needs to be transparency. Numbers, statistics, and outcomes must be grounded in evidence. For example, the rise in tourism cannot be attributed solely to finalising the peace agreement, as claimed earlier in the summer. Such claims make people mistrust both the process and the negotiators that are involved. Premises and expectations must be communicated clearly to prevent another disconnect between the state and society, such as the one seen before and during the 2020 war and the exodus from Nagorno-Karabakh.

Transparency should not rest on the leader’s words but should become institutionalised, ensuring that Armenians inherit accountable state structures capable of navigating geopolitical changes. They should be open and honest with their people, investing in the right decisions to guide Armenia and its citizens toward a more prosperous future, without the fear of being labelled as traitors by right-leaning groups or pursuing short-term electoral goals. This does not mean that every step of the negotiations should be public, but off-the-record conversations with those directly affected by the conflict, its aftermath, and border limitations can help trustbuilding efforts within the Armenian community.

Accountability in domestic politics can significantly influence public trust in the ruling party’s foreign policy. Building capable and accountable institutions for foreign policy, as well as for social, economic, cultural, and educational affairs, is Armenia’s long-term guarantee for securing statehood and a dignified life for its people. Fighting media battles according to the rules of the nationalistic opposition might achieve short-term electoral goals; however, in the long term, Armenia and its people will lose.

Civil society is crucially important to keep the government accountable and strengthen democratic institutions, bridging the gap between the state and the people. While they have pointed out that the Washington agreements do not yet reflect just and holistic peace, civil society should also ask what just peace would look like, and whether parts of it can be achieved even without the government or to support the government.

One gap, perhaps, is addressing the needs of displaced Nagorno-Karabakh Armenians. About 100,000 people now face the painful reality that returning home is an unrealistic chapter, at least in the way they believe it could be or was possible before 2020. As painful as this is, and despite certain political and analytical communities claiming otherwise, Armenians unfortunately have to come to terms with this reality.

Politicising their pain for political gain only perpetuates their in-between-ness, preventing them from building a dignified life in new communities. Instead, economic, social, psychological, and cultural integration projects could help them feel welcome, supported, and able to build meaningful lives. Advocating for their rights in Armenia will help the displaced feel more valued, rather than feeding them unrealistic hopes that further alienate them from one another and eventually push them to emigrate from Armenia as their pressing needs remain unaddressed.

Educational institutions also have a critical role. Schools and universities teaching history, political science, international relations, sociology, and economics must be part of the discussions on reimagining the region.

They should teach students to read, research, and critically analyse the post-2020 processes with a clear vision, respect for perspectives, and the balanced use of quantitative and qualitative tools that different disciplines offer. Critical and inclusive debate about the past, present, and future is the only way to foster open classrooms, where visions for the future replace cycles of grievance and are addressed from a multidisciplinary perspective.

There is still a lack of serious economic studies on how closed borders with two neighbours have affected Armenia’s development or on what the Trump Route might bring, not only in economic terms but also in how it could change lives locally and regionally. Educational spaces should provide intellectually stimulating debate, based on mutual respect and the belief that knowledge is created through dialogue and listening to one another, helping to address polarisation among the public at large.

Long-lasting peace requires introspection. It demands recognising past failures and addressing them, while also acknowledging that change is possible if Armenia itself takes initiative. Moving away from a victim mentality does not mean denying victimhood, but realising that Armenia can shape what the future brings in the region.

People on the ground want calm lives without political turbulence. What they need is transparency, honesty, and collaboration between the ruling party, civil society, and the academic and expert communities. Only then can the agreements signed in Washington or elsewhere become more than words on paper and begin to transform the region’s future.

Constructive engagement could help make the peace process more inclusive at the grassroots, even though it has not begun so at the top. Rather than repeating the same narrative that has dominated since the first clashes between the two peoples, that the other cannot be trusted and coexistence is impossible, and perpetuating stereotypes that deepen mistrust and obscure meaningful regional narratives, the internal discourse needs to catch up with the geopolitical and geoeconomic processes shaping the region and the world. This time, it should seize the opportunity to provide a more dignified life for the people who will continue living in Armenia and to reimagine an integrated region, as romantic as it may sound.