★★★★☆

Ana Urushadze’s 2017 debut film follows a Tbilisi housewife whose secret manuscript unravels the fragile architecture of family life.

Scary Mother (Sashishi deda) is a work that fills the viewer with discomfort, yet stays in the mind long after it ends. Slow, disquieting, and psychologically suffocating, it lingers like a persistent echo, growing more powerful with time.

On paper, the story is simple: Manana (Nata Murvanidze), a middle-aged housewife, writes a novel — her family members know about the writing process, but not about the content. After secretly finishing the text, Manana reads the story aloud to her family, only to horrify them.

Urushadze is less interested in plot than in excavation. The film becomes a study of what happens when a woman begins articulating thoughts she has spent a lifetime thinking about, and how threatening that act becomes to those invested in her silence.

Creativity is presented not as inspiration but as compulsion. Manana scribbles sentences on her hands to preserve them, even shielding the ink from water while bathing. Writing is portrayed as a physical need, almost an illness. Her domestic environment, meanwhile, is built on ritual politeness and rehearsed affection. Her husband (Dimitri Tatishvili) using pet names like ‘honey’ or calling her ‘lovely’ all the time begins to sound increasingly artificial, as if he is reciting lines from a script titled ‘happy marriage’. The more Manana retreats into authorship, the more his performance intensifies and the more fragile it appears.

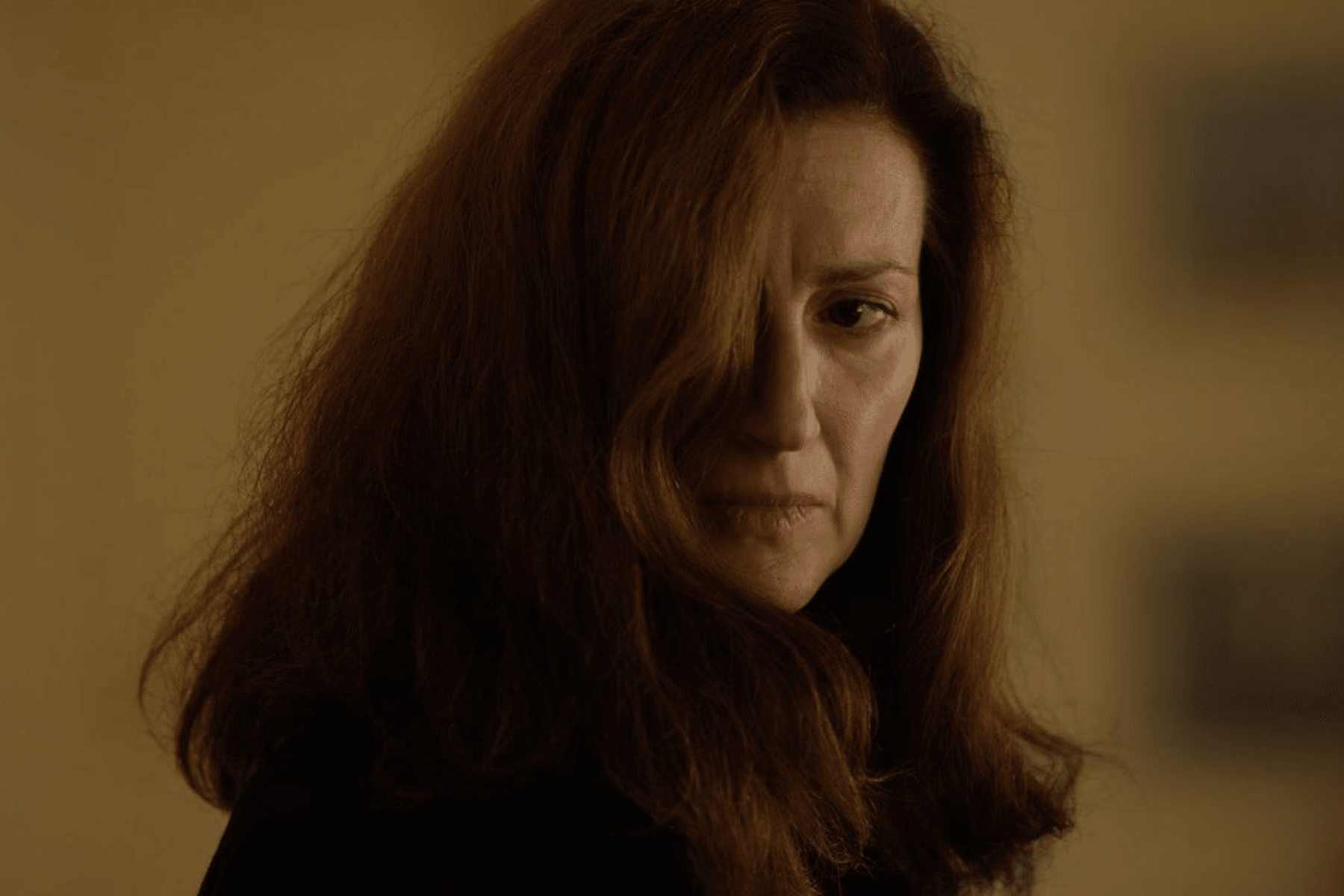

One of the film’s most striking sequences occurs when Manana finally reads her manuscript out loud at the dinner table. The camera begins with a close-up shot on her face, then slowly pulls back until the entire family enters the frame. The movement is precise and merciless, transforming the scene into a box of collective discomfort. Each expression becomes part of a silent chorus reacting to words that cannot be unheard.

Manana’s manuscript is transgressive. Though the audience never hears the full text, its fragments and reactions suggest a work saturated with explicit erotic imagery and violent emotional honesty. Some who encounter it, including potential publishers, dismiss it as pornography rather than literature. What disturbs them is not merely sexual content but the fact that such content comes from a woman they expect to remain contained within maternal respectability.

Urushadze frequently frames Manana in profile as she describes dreams of transforming into a bird, using the actress’s features themselves as a form of visual commentary. This transformation is estrangement from family, from society, and perhaps from herself.

Supporting characters deepen the film’s thematic architecture. First comes the stationery shop owner, the only person who instinctively recognises the value of Manana’s writing and encourages her to pursue publication, sensing an author where others see a problem. Then there is Manana’s father, a translator who unknowingly works on her manuscript, believing it was written by a man. His admiration for the text reveals a quiet irony: he can appreciate its intellect and eroticism only when he does not associate it with his daughter.

Visually, Scary Mother constructs a world divided between two dominant colour palettes. Much of the film is drenched in cold greys and wintery, snowy blues, reflecting the geometry of Soviet-era apartment blocks. The architecture itself feels grotesque, with weird balconies, concrete corridors, a strange bridge linking Manana’s building to the stationery shop across the way.

In contrast, the hidden room where Manana retreats after running away from home is saturated in red light. Red floods the frame, evoking both flesh and danger, desire and alarm. In an interview, Urushadze noted that the colour resonates with a childhood image of Manana’s mother’s red hair, suggesting buried memories that remain unresolved. It also echoes the erotic charge of Manana’s writing.

Urushadze reinforces this visual strategy with sound design that leans toward horror aesthetics. Silence stretches uncomfortably long, ambient noises seem amplified. As Manana withdraws further into authorship, both she and the film darken. Her husband’s behaviour grows desperate, while she herself appears increasingly detached from social reality. But at the same time, the narrative does not ask whether Manana is right or wrong — instead, it poses a more interesting question: what if honesty itself is incompatible with the roles society assigns?

Within contemporary Georgian cinema, Scary Mother stands apart. Rather than focusing on familiar national motifs or social realism, it adopts a postmodern tone that feels unusual. Some viewers may find its ambiguity frustrating. Certain motivations remain obscure, some narratives are not closed. But these gaps feel intentional, making the film all the more interesting.

Film details: Scary Mother (2017), directed by Ana Urushadze, is available to stream on Cavea+.