With 24-hour shifts, collective responsibility, and heavy surveillance, employees of Georgian supermarkets complain of being exploited. While supermarket owners justify the hard working conditions with a need to improve customer service, trade unions say the problem lies in a lack of regulations.

With 24-hour shifts, collective responsibility, and heavy surveillance, employees of Georgian supermarkets complain of being exploited. While supermarket owners justify the hard working conditions with a need to improve customer service, trade unions say the problem lies in a lack of regulations.

Cashier, storekeeper, and cleaner

Twenty-five-year-old Gvantsa (not her real name) started working at supermarket chain Nikora several months ago. She earns ₾450 ($165) a month working two 24-hour shifts a week. She has another job as well, but doesn’t want to give details; she is afraid she may lose her jobs if she speaks publicly about them.

During the day, Gvantsa checks for expired products along with working as a cashier. At night, apart from serving the clients, she also cleans.

Gvantsa tells OC Media that the contract she signed never specified her duties. The new employees decide themselves what position they will be working in. If she wants to keep her job she has to fulfil other physical duties along with being at the cash desk at night. Every night the boss leaves her a list of tasks and in the morning she gets the list back with his signature.

The tasks include removing all the products from the counters, cleaning them and putting the products back, also placing the new delivery in the storeroom; sweeping and cleaning a 200-square-metre area; cleaning the rooms of the supervisors, as well as the bathroom and the windows. Like other cashiers of Nikora, Gvantsa does all these tasks during the night shift. She also has to count the sum of money during the day in order to report it to the inspector in the morning.

She adds that she should be settle the accounts in the morning, but she gets too tired overnight and usually does it before morning comes.

During night shifts there are only two members of staff at her branch of Nikora, her and another who is responsible for the meats section.

‘It’s forbidden, but I still taught the other girl how to work at the cash desk and she works there while I’m cleaning the place or counting the money. I am afraid I can make a mistake if I am tired while counting the money and this will be a bigger problem than anything else’, she says.

During the shift cashiers have three 15-minute breaks. She has to manage eating during the break, while spending money from her own salary.

‘If there are many customers in the supermarket during my break and if I have to stand in a crowd with my own lunch, the whole break is spent in it. If I am late for one minute after the break, I will get a rebuke’, she adds.

Cashiers have to use a changing room during their breaks. The room is about 10 square metres big. If they want to eat or drink coffee they have to go there in shifts as they do not fit.

There are surveillance cameras everywhere in the supermarket, except the toilet.

‘There is a camera even near the sink. I am so tense because of it. Sometimes I think that they watch us even in the toilets’, Gvantsa says.

The monitoring service controls staff 24 hours a day. Gvantsa says that she and the other members of staff are not allowed to bring or drink water in the main hall of the supermarket. They give their phones to the manager at the beginning of their shift and can only use them during breaks. If they break any of the rules they will get a rebuke, and will be fined next time around.

A 2017 research conducted in seven supermarkets (Nikora, Ori Nabiji, Fresco, Carrefour, Vejini, Europroduct, and Spar) by the Georgian Trade Unions Confederation (GTUC) confirms Gvantsa’s claims. According to the research, 24% of the 493 interviewed supermarket employees perform additional duties. 69% of respondents declared that they seldom manage to take a short break, while 4% is unable to take a break at all.

‘Improving customer service’

A spokesperson for Nikora told OC Media that surveillance cameras were installed to protect company and staff property.

‘We’ve had a number of cases where the property of employees was violated. Cameras helped us identify such cases. All employees are informed about them’.

The administration of the supermarket said that all branches have cleaners.

As for restrictions on staff, the administration said the goal is to improve customer service, security, and improve staff work performance.

‘Employees aren’t banned from bringing their phones to the hall, but they are banned from using them in the presence of customers, which aims to improve customer service’, the company’s spokesperson said.

Collective punishment

On 8 February, a group of employees of supermarket chain Fresco published a statement on Facebook criticising labour conditions in their stores. after an audit was conducted in several branches revealed that some branches were operating at a loss, the company cut employees salaries by 50%.

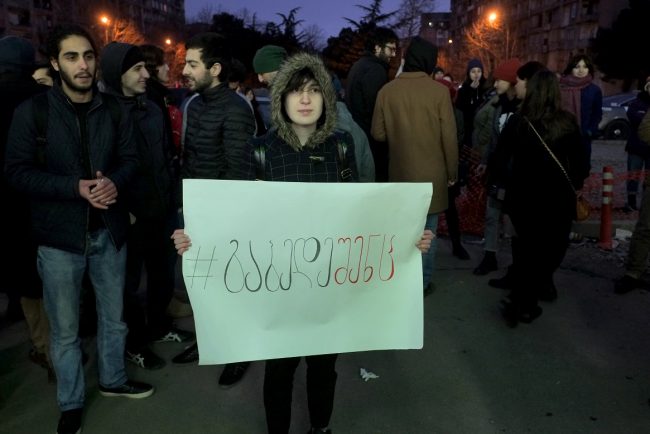

About 80 people left their jobs and protests lasted for several days. Former employees spoke about exploitation at work.

‘I was working 12-hour shifts five days a week. I didn’t know at first that this was in violation of my labour rights. We used to ignore lots of things, but when they cut our salaries by 50% we decided to publish an open letter and leave the job’, Mariam Lashkhi said during a protest on 13 February in front of one of Fresco’s Tbilisi branches.

Staff accused the company of unfairly docking wages, not paying for overtime, forcing staff to pay for shortfalls in the cash register from their own pockets, and applying undue pressure on workers. Fresco denied all accusations.

Additionally, in December, the Public Defender condemned video surveillance in the female staff changing rooms for unjustifiably interfering with the privacy of the employed women and accused Fresco of ‘gender discrimination expressed in sexual harassment’.

According to the GTUC’s research, 76% respondents employed in seven surveyed supermarkets never received remuneration for working overtime, while 80% never even received a bonus for working during public holidays. Additionally, 41% of respondents had their salaries deduced on different occasions, for example for not wearing the uniform or the cap. 18% never received an explanation as for why their salary was reduced.

Total control

Natia Mebonia worked as a security guard in Fresco for a month and a half, earning ₾350 ($125) a month working two 24-hour shifts a week. As well as watching for theft, she had to observe when staff arrived, took their breaks, and how hard they were working.

She told OC Media that the month and a half at Fresco put a psychological strain on her.

‘It was a double pressure for me. If a cashier was late by two minutes after a break, I had to dock their wages. If a cashier, after spending 24 hours standing in the hall, found it difficult to smile at customers, I had to reprimand them. I myself was constantly being monitored by surveillance cameras’, she told OC Media.

After she left the job, the company refused to pay her for her last month of work. She approached trade unions for help and managed to win compensation. Since then she has joined the United Georgian Trade Unions working to raise awareness of difficulties faced by supermarket employees in Georgia.

‘We go to supermarket branches and introduce staff to the labour code and to their rights. It’s easy to work with some, as they stand up to their employers. But most generally prefer not to say anything, because even this small salary is very important to them’, she says.

After the protests outside Fresco, the Ministry of Health and Labour inspected the chain and issued recommendations.

According to documents obtained by OC Media, the violations identified during inspection were that workplace injuries were not recorded; there were no preliminary medical examinations of staff; fire safety systems needed improvement; employees were not equipped with individual protection tools; first aid kits were outdated; and there were faulty ventilation systems in the kitchens of several branches.

Other complaints employees were protesting against were not mentioned.

Beka Peradze from the Health Ministry’s Labour Inspection Department told OC Media that following the inspection, Fresco improved conditions; the company did not wish to comment on the matter.

A pattern of exploitation

In January 2017, the Tbilisi-based Human Rights Education and Monitoring Centre (EMC) published research evaluating labour inspection mechanisms and labour conditions in Georgia. They interviewed a number of employees of Georgian supermarkets, where staff turnover is particularly high.

‘We have to work a lot and many people just can’t bear it. I’ve been working here for five months and am considered a senior worker, because people usually leave in a month because they can’t take it’, the research quotes one worker as saying.

Most of the supermarket employees interviewed complained that their salary as a full-time cashier was not enough to be financially independent, and just acted as an extra support for their family.

The report stated that overtime pay is the same as for regular hours and payment for night shifts is the same as for the day shifts.

According to the report, some companies completely ignore staff’s right to take breaks, allowing only short breaks with insufficient time to eat or even smoke. The rules usually set out fines to discipline employees, which are taken directly from their salaries.

The report says that a lack of staff often creates problems in distributing work, forcing employees to do extra work for no additional pay.

‘I carry heavy loads and my kidneys often so much that I find it hard to breathe. Now when I lift heavy loads I have to take medicine to feel better’, one interviewee said.

According to the research, another problem is the security system at the supermarkets. Some companies completely removed heads of security, which is why cashier-consultants have to use a special button to call a guard. The response time usually takes about 10–15 minutes.

The employees say that having surveillance cameras is not a sufficient safety guarantee, especially when working at night.

Few regulations

Since being established in 2015, Labour Inspection Department has been responsible for labour safety in Georgia. however, its mandate is restricted, as they can only inspect workplaces if they get prior permission from them. They do not have the power to impose fines or any other sanctions against companies. Labour inspectors simply give out recommendations and it is up to the goodwill of employers to fulfil them.

The department is still in a pilot phase, and next year parliament is expected to amend the labour code to better define its role.

The current draft suggests that the department will only inspect enterprises involving dangerous or harmful conditions with a high risk of physical trauma. The government will define the list of such enterprises.

Dimitri Tskitishvili, a member of parliament from the ruling Georgian Dream party, said in the parliament on 12 July that the reason for restricting the type of enterprises to be inspected is a lack of human and financial resources. He added that the law will come into force as a pilot. In the meantime, the government will try to spread the mandate of the law on other workplaces, including the service sector, he said.

According to the draft, the labour inspection will inspect enterprises from the list once a year without permission from employers. The inspection will need permission from the court to inspect the service sector.

Lina Ghvinianidze, director of social rights program at EMC, says that the draft completely contradicts the model of effective labour inspection. She also says that although there are no hazardous conditions in the service sector, there are still health risks.

‘Working extra hours, additional physical load, lifting heavy weights may create health problems for the employees. That’s why it’s not right to talk about security and health issues in relation to only enterprises with dangerous and hazardous conditions’, she told OC Media.

The draft still is going through discussions with the government, trade unions, business associations, and the civil sector. After the second hearing the draft will be discussed on plenary session and then will go through the committee hearings before being finally approved.

Lina Ghvinianidze hopes that the parliament will foresee recommendations of the NGOs and trade unions during the second hearing and the law will apply to the other sectors as well.

‘Everything will happen step by step. We are now preparing the ground for comprehensive inspection’, Beka Peradze from the Health Ministry’s Labour Inspection Department told OC Media.

He also says that considering the occupational traumas and mortality statistics, the law has to apply to the hazardous workplaces in the first place and step by step it will apply to the service sector, including the rights of people employed in the supermarkets.

‘There are risks in every kind of job. I agree that the law should apply to other sectors as well, but now we should start with more dangerous workplaces. The ministry took great steps from 2015 in regards of inspection, but everything has its own time. Service sector will be the next stage’, Peradze adds.

This article was prepared with support from the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Regional Office in the South Caucasus. All opinions expressed are the author’s alone, and may not necessarily reflect the views of FES.