Georgia’s education ministry has announced plans to scrap standardised graduation testing for secondary school students and to drop one of the four Unified National Exams — the standardised entrance exams for Georgian universities.

The ministry unveiled their ‘comprehensive reforms’ on 28 January and 6 February, followed by a presentation in Parliament on 7–8 February by Education Minister Mikheil Batiashvili.

In order to graduate from secondary school, students were previously required to pass exams set by the education ministry in geography, biology, chemistry, and physics in year 11 and then in Georgian, history, foreign languages, and maths in year 12.

Schools will now grade secondary students themselves, with students required to score at least 50% in every subject to graduate. The government argued that this would more fairly reflect different schools’ curriculums.

Also in the reforms, starting from 2020, those wishing to apply for Georgian universities will no longer have to sit the general intelligence test as a part of the United National Exams.

Prospective students will still sit exams in Georgian and foreign languages — with the final exam, either in maths or history, decided by universities based on the subject students wish to study.

The ministry argued that this change would ‘enhance the autonomy of universities’.

Previously, students could choose themselves which final exam to sit, from literature, maths, history, geography, physics, biology, art, or civic education.

Georgia’s Unified National Exams — introduced in 2005 by the government of the United National Movement (UNM) party — were widely hailed as a success story in Georgia’s fight against corruption in the education sector.

In 2007, Washington based watchdog Freedom House said that the centralised entry exams had ‘virtually cleaned out the notoriously corrupt process of admission examinations in universities’.

Prime Minister Mamuka Bakhtadze, who named education reform as his ‘absolute priority’ prior to being appointed prime minister, promised the reforms would be accompanied by increased investment in education, including investment in school infrastructure and raising teachers’ salaries.

He promised to make schools more inclusive for children with special needs, in addition to keeping students safe from violence.

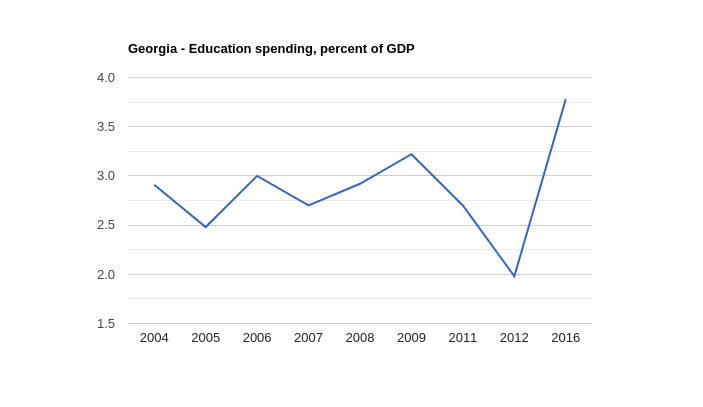

On 3 February, he announced that at least 12% of GDP would be spent on education. In 2017, government expenditure on education was just 3.8% of the GDP.

In the 2019 state budget, the government increased funding for the Ministry of Education by ₾47.5 million ($18 million), to a total of ₾1.5 billion ($565 million).

However, local watchdog Transparency International — Georgia said the government had failed to address an absence of ‘specific goals, intermediary and final outcomes and indicators’ in the ministry’s school education programme.

‘A return to corruption’

The latest reforms were roundly criticised by current and former members of the UNM.

Former education minister Kakha Lomaia, who oversaw the introduction of the Unified National Exams, warned on Facebook that ‘corruption at admission exams could be back’.

On 6 February he said education reforms had been ‘most dynamic in 2005–2007’, but conceded that after this they had slowed and faced many challenges.

He said that since 2012, education reforms had fallen victim to ‘political retribution’, against the ‘leftovers’ of the United National Movement.

UNM conceded victory to Georgian Dream in the 2012 parliamentary elections.

Dimitri Shashkini, who served as education minister from 2009–2012, weighed in on 5 February saying during a press conference that ‘graduate examinations need improvement, not abolishment’.

Shashkini also warned of a return of bribery. ‘Children will pass tests in exchange for bonbonnieres, fried pork, and money’, said Shashkini.

The same day, Sergi Kapanadze, an MP from the opposition European Georgia Party, which split from the UNM in 2017, called the initiative to axe secondary school graduate tests ‘badly thought-out’, and vowed to draft a law that would make such tests compulsory again.

‘Political control’, big dropout

The government introduced standardised testing secondary school graduation exams in 2011 under Shashkin, claiming that it would improve the quality of teaching.

However, according to Tamar Mosiashvili, an educational expert at the Tbilisi-based Civic Development Institute, the tests were used to create ‘extreme political and administrative control’ over schools. She said there was no evidence they contributed to any improvements in education.

Mosiashvili told OC Media that the number of students who failed secondary school graduation exams was used by the government as an ‘instrument’ to sack school directors.

Mosiashvili also said students who wished to go to university were tested again in the same subjects, creating ‘duplicate’ testing.

Education consultant Simon Janashia, who headed the National Curriculum and Assessment Centre between 2004–2009, told OC Media that sacking school heads on the grounds of poor secondary school exam performances led schools to expel pupils they expected to fail en masse.

‘There is an argument that these tests brought these children back to books, but that’s forgetting the fact that a big portion of [students with poor grades] entirely left school due to these tests, many directly entering the labour market or criminal world’, Janashia said.

Introducing the reforms to Parliament, Education Minister Mikheil Batiashvili said that around 50,000 children had dropped out of school early ‘in recent years’, and that the government had to offer them alternatives, including professional vocational programmes.

Overtesting

Both Janashia and Mosiashvili agreed that centrally administered testing was used as a tool to evaluate how the school system was performing.

Mosiashvili said that this led to overtesting, and to an increase of private schools, which she said enjoyed greater freedom.

‘If we continue this way, we’ll ruin public schools’, she said.

According to Janashia, the idea behind introducing the secondary school graduation exams was to reduce the number of Unified National Exams, ultimately ending up with eight school graduation tests and just one university entrance exam — the general intelligence test.

Janashia said this did not happen after the change of power in 2012 largely due to the economic interests of school teachers who also worked as private tutors.

Despite the reforms drastically cutting the number of tests, Janashia said this would not ‘solve the problem of the system being oriented on tests’.

Nevertheless, he said the change might ease the burden of parents who had to pay for private tutors, sometimes for both school graduation exams and then the Unified National Exams.

‘School teachers tutoring their pupils privately also remains problematic’, Janashia told OC Media. He argued that this jeopardised both the ‘integrity of the evaluation system’ at schools, as well as teachers’ motivation to concentrate on the quality of teaching at school, including in private institutions.

Shadow education

The Education Minister argued in front of MPs on 7 February that it was ‘impermissible that the main provider of education at 11th and 12th grades is a private tutor’.

Batiashvili argued that the new policy would be oriented towards ‘strengthening schools’ rather than focusing on testing, and said the current model pushed parents to pay tutors to prepare students for their graduation tests.

He also criticised the general intelligence test as being a ‘separate enterprise, with consultants, literature, and experts’, causing a gap in test results between Tbilisi and the rest of Georgia. As a result, according to Batiashvili, the tests worsened social inequality.

[Read Bakar Berekasvhili's opinion on OC Media: Georgia's capitalist education reforms are a breeding ground for inequality]

Speaking to OC Media, Mosiashvili said that after year 10, students tended to only concentrate on preparing for their graduation exams, which involved ‘acquiring tricks and skills for solving’ these tests, rather than actual learning.

She said that it ‘strengthened the shadow economy of private tutors in education’ and diminished the teaching process in schoolrooms.

In regards to the Unified National Exams, the university entry tests, Mosiashvili said that ideally, it should be up to the universities rather than the state which subjects they believe are required to gain entrance into their programmes.

Janashia told OC Media that the Unified National Exams were competitive by nature and would remain so. Therefore, dropping the general intelligence test ‘will not change much’ in terms of tackling demand for private tutors, which was caused by competition for university places.

According to him, letting universities set other kinds of criteria for applicants would be better and would allow greater autonomy for universities.

11 February 2019

11 February 2019