A cog in the ‘machine of evil’: ex-TV Imedi employees on working for Georgian Dream’s spin machine

TV Imedi has a stated goal — to prevent the opposition from gaining power — a goal former employees say has overtaken all questions of ethics.

When Tamar Sharikadze joined the news desk at TV Imedi in September 2019, she says she was still able to produce some reports that questioned the government’s performance, at least regarding infrastructural issues in the countryside.

However, as the 2020 parliamentary elections approached, she was asked to stop.

‘[Those reports] were dropped and never returned to. On the contrary, the coverage shifted to how the regions were thriving’, recalls Sharikadze, who spent four more years at Imedi before resigning in June 2024.

‘After I left, the coverage of politics at Imedi worsened even further’, says another former Imedi journalist, Keti Partskhaladze, who spent 10 years at the channel before resigning in 2023. ‘Today it has nothing to do with journalism.’

Since Georgian Dream came to power in 2012, Imedi has had a distinct pro-government slant. But over the past few years, as the ruling party tightened its grip, that slant has turned to something more sinister — with the channel taking to unquestionably repeating Georgian Dream conspiracy theories and attacking government critics both inside and outside Georgia.

From relative neutrality to openly pro-government

Imedi’s critical stance towards the opposition is rooted in its history with the former ruling United National Movement (UNM) party.

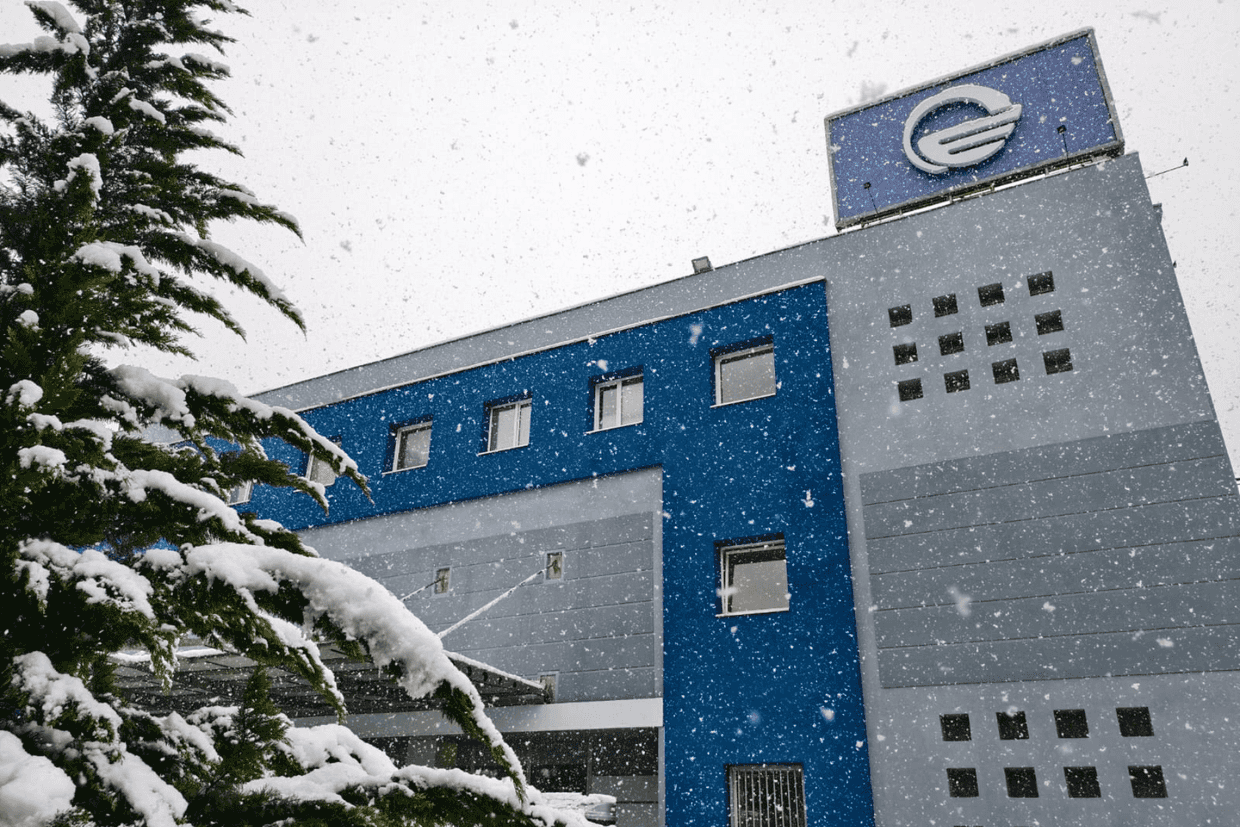

In November 2007, following the violent suppression of protests against the then UNM-led government, riot police raided Imedi’s headquarters, accusing the channel of being involved in an ‘attempted coup’, taking it off the air. The channel, at the time owned by Badri Patarkatsishvili, was seized by state loyalists and transformed into a pro-UNM outlet.

In 2012, shortly after Georgian Dream came to power, the Patarkatsishvili family regained ownership of Imedi. Following this, the channel’s management and staff underwent significant changes, and its editorial stance began to change.

According to media monitoring reports by the Georgian Charter of Journalistic Ethics, an independent union of journalists, during the 2013 presidential and 2014 local elections, Imedi’s news and political programmes were assessed as largely balanced and neutral, despite some instances of coverage favourable to the government.

By 2016, amid increasing polarisation in the Georgian TV industry, Imedi had solidified its position in the pro-government camp.

In 2018, following Georgian Dream’s poor performance in the first round of that year’s presidential election, Imedi openly declared a new goal: to ensure that UNM would never return to power. Soon after, negative coverage of Georgian Dream opponents intensified, and critical voices gradually began to disappear from the channel.

Over the following years, numerous high-ranking figures within Imedi highlighted this goal.

In 2019, the channel’s then-director, Nika Laliashvili, told journalists during a meeting to forget about balanced coverage since they were ‘at war’, had become ‘biased’, and took an ‘anti-UNM’ stance. More recently, Imedi’s current owner, Irakli Rukhadze, stated prior to the 2024 parliamentary elections that the channel only exists so that ‘UNM and its affiliates would never return to governance of the country’.

‘The problem is how you think’

According to former Imedi journalist Keti Partskhaladze, a number of the channel’s employees only learned about the channel’s openly anti-UNM stance in 2018 live on air.

‘Some of us had a sense of discontent, thinking that we should have at least been informed in advance. We should have been given time to decide if we wanted to work on such a channel or not’, Partskhaladze tells OC Media.

She realised that she would no longer be able to freely cover political events and decided to resign. However, her supervisors persuaded her to stay by allowing her to work on culture.

The following year, Tamar Sharikadze joined Imedi as a political journalist. She tells OC Media that the channel’s policies were not an issue for her, as at the time, she was indifferent to both the ruling party and the opposition.

However, she soon learned that the channel’s targets were not limited to just UNM.

One of her first conflicts at work occurred in 2022, when Georgian Dream and its associates launched a campaign to ‘defend’ 18th century King Erekle II from contemporary critics, who condemned him for signing a treaty with Russia. As Sharikadze recalls, the then-head of Imedi’s news department, Natia Toidze, instructed her to make a report about how the US-funded RFE/RL had ‘insulted’ the king and his wife in a 2020 article. When Sharikadze read the article, she remembers feeling that making such a report would be misleading.

‘We had a huge conflict about this […] I remember she used an offensive phrase that I will never forget: The problem is how you think’.

In the end, Sharikadze did not make the report, after which Toidze did not allow her to produce any further reports.

‘I spent several months in the newsroom with books, watching every nice TV series that existed’, Sharikadze recalls, joking about how she tried to kill time during this period.

Toidze, who is still employed by Imedi, told OC Media that Sharikadze’s claims were ‘absolute nonsense’.

Imedi’s editorial shift on certain social issues also gradually became aligned with the ruling party. In particular, Imedi went from actively covering the challenges faced by Georgia’s queer community to itself creating homophobic and transphobic content, particularly as a way to discredit Georgian Dream’s opponents.

One of Imedi’s most recent targets was professor and activist Nana Dikhaminjia, who was referred to as an ‘LGBT propagandist’ and a ‘follower of fascism’ by a news anchor after she confronted Georgian Dream’s parliamentary leader Mamuka Mdinaradze over the ruling party’s policies.

According to Sharikadze, Imedi’s editorial policy has long since surpassed the ‘never-UNM’ line: now, anyone who criticises the government’s policies is considered a natsi — a term for UNM members and supporters.

‘[Ukrainian President Volodymyr] Zelenskyi turned out to be a natsi, members of the European Parliament turned out to be natsebi, too. In the end, I became a natsi as well! How is everyone a natsi?!’ Sharikadze asks.

‘Sitting in the editing room, I was crying’

Another incident Sharikadze recalls took place following Russia’s full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022. At the time, Georgian Dream began pushing a conspiracy theory that certain foreign powers — later termed the ‘Global War Party’ — were trying to drag Georgia into the conflict and that Georgian officials, such as then Prime Minister Irakli Gharibashvili, were the only people protecting the country from this threat.

According to Sharikadze, it was at this point she witnessed that detailed instructions were being provided by the government press service to journalists on how to edit the lengthy videos about Gharibashvili’s visits to different regions.

‘Direct [instructions] would come, things [detailed] in brackets, saying stuff like: “He [Gharibashvili] says this here, and it should be included as background noise”, or “He kicks the ball here, it should be highlighted” etc’, she says.

She recalls that one of her colleagues was reprimanded for shortening an initial 11-minute report on Gharibashvili’s regional visit to six minutes before airing it.

‘Someone from the government called and asked why it was only six minutes and why it was missing the specific background noises that were indicated [in the instructions]’, Sharikadze says.

When it was Sharikadze’s turn to cover Gharibashvili’s next working trip, she had enough material to create a 25-minute report. Given the length, she shortened the material, but says this caused her serious stress, as she didn’t want to receive a reprimand like her colleague.

‘I’ve worked before in a fire, during protest dispersals and didn’t get nervous. But at that moment, sitting in the edit room, I was crying’, Sharikadze says.

According to Sharikadze, such direct intervention by the ruling party was rare. More commonly, journalists were given instruction by higher-ups in the newsroom.

However, she recalls instances when journalists from other pro-government TV channels, including Rustavi2 and POSTV, arrived at shoots with identical materials as those provided to Sharikadze by Imedi’s news producers. She believes these materials were distributed by the ruling party in a coordinated fashion.

‘For example, an [opposition politician] says something and we’re making a story about it. The exact same statement, the same video, edited the same way, was also provided to my colleagues, for example, from Rustavi 2 and POSTV’, she says, adding that those were ‘external instructions’.

During this same period, Partskhaladze was exclusively covering cultural topics for Imedi’s flagship analytical programme, Imedis Kvira (‘Imedi’s week’). However, as the 2024 elections approached, avoiding political content became increasingly difficult.

‘In September [2023], the new TV season began, and at the very first meeting, it was announced that we had a declared editorial policy. It was an election year, and the programme would work in support of the government with open statements’, Partskhaladze recalls.

She says the programme’s host assured her that non-political content would still remain. Yet, just a month after that conversation, she was asked to create a report summarising Georgian Dream’s 11 years in power, using materials provided by the government’s PR department highlighting their achievements during this period.

‘It was a government PR piece, not journalism […] I knew for certain that I couldn’t produce the report as I saw fit — it was impossible to take a critical stance toward the government’, she recalls.

Realising that ‘worse was yet to come’, Partskhaladze resigned. She publicly shared the reasons for leaving the channel in a post on Facebook, which was later deleted.

‘Many friends from the channel reacted negatively [to the resignation post], as if I had contributed to bullying — bullying of those who remained at the station. Yet, I had hoped for their support. Wasn’t I, too, a victim of the circumstances?’ she says.

‘Look what was on your channel!’

‘Fake dream, fake hope!’ read a poster at one of the nightly anti-government protests following Georgian Dream’s announcement to halt the country’s EU membership bid. The text was a play on words — in Georgian, Imedi means hope. However, for many protesters, the TV channel has long since lost its original meaning.

During the first days of the ongoing demonstrations, Imedi focused on telling its audience that the police, under ‘physical and psychological pressure’, were using ‘special means’ only against ‘aggressive citizens’, repeating the narratives of the ruling party and its associates. Barely any stories mentioned the demonstrators and journalists who were brutally beaten, tortured, robbed, and insulted by the masked and unidentified officers.

Such coverage was the breaking point for Zviad Barateli, then-Deputy Head of Imedi’s video editing team, who resigned in December after seven years at the channel.

‘I didn’t want to be a part of harmful propaganda that Imedi was producing’, Barateli tells OC Media, noting that he found it unbearable to watch how the channel referred to protesters in their coverage, among whom were some of his own friends and relatives.

‘When I realised that we were losing everything, that we were losing our European future, I didn’t want to participate in that [propaganda] anymore’, he adds.

Barateli also criticised what he saw as Imedi’s attempts to downplay the scale of the protests.

‘When I see with my own eyes that there are a lot of people at a protest and Imedi’s drone captures a shot at a specific time and specific part of the rally where fewer people appear than there actually are […] I didn’t like that I had to [participate in such manipulation]’.

According to him, any internal rebellion against such manipulative practices was doomed to fail from the outset.

‘Every frame and every report that goes on air is always checked and monitored. Every employee knows in advance how things should be done, because even if something different were to go on air, it would later be re-edited to ensure that the altered version is broadcasted’, he says.

According to Sharikadze, similar tactics were used during the protests against the foreign agent law in the spring of 2024.

‘In my live broadcast, I honestly said that the water cannon truck started moving, special [police] forces were approaching, and the Ministry of Internal Affairs began dispersing the crowd, but at the same moment, there was nothing in the [live] footage. They brought me back into frame when the protesters began building barricades’, she recounts.

According to her, while she was describing the events, the channel’s drone was flying over a distant street, where there were not many protesters nor any police intervention taking place. She faced discontent from the protesters because of this.

‘I remember someone insulted me, and I got really angry. I asked, “Why are you insulting me? I was standing in front of you, I inhaled gas with you!” […] And suddenly that person showed me my own broadcast, saying “You were standing here, yeah, but look what was on your channel!” I was speechless, I couldn’t say anything’, Sharikadze recalls.

When she later asked her boss why footage of the activist Davit Katsarava, who was beaten by police during the foreign agent law protests, wasn’t aired, her boss only replied, ‘You know why’.

Though Imedi’s owner Irakli Rukhadze maintained the channel’s editorial independence in a recent interview with RFE/RL, he himself noted that no coverage was given to the similarly severe beating of journalist Guram Rogava by police during the protests due to Rogava’s prior criticism of Imedi.

Rukhadze also emphasised that the channel would remain ‘on Ivanishvili’s side’ as long as there was an ‘opposing side’, adding that if Imedi did criticise Georgian Dream, this would lead to ‘the person I fear the most’ returning to power, referring to former President Mikheil Saakashvili.

‘I am one of those who created this evil machine’

Against the backdrop of the widely condemned laws passed by Georgian Dream and the violent suppression of protests in 2023–2024, around a dozen Imedi employees from all sectors publicly left the channel.

Sharikadze left Imedi in June 2024, after refusing to prepare content that ‘encouraged violence’, as she wrote on social media.

According to Sharikadze, the content in question concerned a group of men accused of attacking UNM’s central office in Tbilisi on 1 June. The version of events presented by Imedi suggested that the attack followed an act of aggression by UNM’s security guards towards the group, and Sharikadze says she was asked by her producer to avoid using the word ‘attack’ in her coverage.

Sharikadze says she refused, believing that Imedi’s version of events lacked evidence, and that such a story could encourage similar practices in the future.

As she recounts, her refusal led to a conflict between her and her producer, and eventually an intervention by the head of the news department, Natia Songhulashvili.

Sharikadze says that she explained to Songhulashvili her reasoning, adding that for her, ‘both sides are absurd’, indicating her antipathy towards both UNM and Georgian Dream.

‘Regarding this, Natia said to me, “So you think the other side is also absurd? That means you don’t agree with the channel’s editorial policy, so you should make an appropriate decision and leave” ’, Sharikadze recalls. That was her last day with Imedi.

‘I still stand by my position that there is no editorial policy that condones violence. If that’s the case, you're just an unmasked titushka [thug] doing much worse than beating one person, because you’re convincing many people that someone deserves to be beaten’, she says.

Following Sharikadze’s resignation, Songhulashvili issued a statement noting that ‘there is no place at Imedi for those who avoid calling the UNM violent and look for excuses to avoid critical reports about them’.

OC Media reached out to Songhulashvili for comment, but did not receive a response.

According to Sharikadze, she did not leave the channel earlier because she had convinced herself that she was not responsible for creating any overtly propagandistic stories. However, she has since realised that this was a mistake.

‘Everyone in a television station, from the janitor to the director, is responsible for what goes on air, but I realised this later’, she says, noting that she became ‘one of the cogs in this system’ and was ‘one of those who helped create this machine of evil’.

Sharikadze adds that during her time at Imedi, the majority of journalists still openly expressed their opinions on specific issues and criticised certain issues within the channel. Now, however, such voices have been silenced.

‘From what I observe from a distance or hear about […] the people who actually protested have gradually stepped back’, she says.

According to Barateli, while there are still people at Imedi who are dissatisfied with the current reality, they continue working due to a variety of reasons, including financial necessity.

Sharikadze, who now creates current affairs content for her YouTube channel with several friends, says she does not have a stable income since leaving Imedi, but that eventually she came to the conclusion that she could not ‘betray’ herself.

‘I also had that comfort: a stable income, comfortable assignments […] You’d have to be a fool not to like this. [But] I just can’t figure out how much all of that weighs compared to being true to yourself’, she says.