At a noisy birthday party, one-year-old Narek covered his ears and began to scream, overwhelmed by the chaos around him. His mother, Lena, stepped outside in tears, feeling lost yet determined.

Given Lena’s pedagogic background, it was not difficult to realise that Narek was different from other children his age at only one-and-a-half years old. She noticed he had begun doing the same things constantly, like spinning rings or watching the same part of a video over and over. Up to that point, however, everything had been progressing naturally.

‘For instance, we were asking him to clap or follow the light; he was doing it perfectly. But that’s one of the secrets of this syndrome: everything goes just as it was meant to for that age, then suddenly changes’, Lena recalls.

Meanwhile, Lena’s husband, Levon, claimed that there was no problem, that she was just tired and exhausted. But when she insisted that their son needed to see a psychiatrist, he agreed just to make sure that the concerns she had were unfounded. Eventually, they ended up face to face with Narek’s diagnosis: autism.

‘When the specialist announced the syndrome and mentioned that it’s going to be forever, I realised that I was in over my head, with more responsibility than I could manage. It was a verdict’, Lena says.

Now more mature and with more experience, Lena reflects on her emotions in a different way.

She remembers how people would stare at her son everywhere because he was acting differently from other children his age and how they would ask questions about whether he had a problem.

At that time, she didn’t know how to answer.

‘I never felt ashamed of him, but I felt bad and tried to hide the problem, hoping that one day it was going to be solved. The most difficult nuance was that it seemed I should justify that my child had an issue he was not to blame for. For a moment, I found myself isolated from the whole world, and that’s the time when one should face the problem face to face’.

Today, however, she says it’s not even important what other people might think.

‘The only responsibility we had was to be happy’

The moment of awakening was when Levon got a job offer from Germany. The family packed everything in preparation for the move, but suddenly the German Embassy refused to give them a visa.

‘We were in shock and the reality hit me hard. We understood that there were two choices: suffering or accepting. Life is a choice and sometimes you just need to accept the situation and find your right angle. We chose happiness for Narek and ourselves. We realised that the only responsibility we had was to be happy’, Lena says.

During the interim period, Lena’s daughter Mary, six years older than Narek, stayed with their relatives for a month.

‘My mom and dad explained to me that Narek needed rehabilitation and they would have to travel a lot to make his life better. I knew that Narek was different; now I know he is unique, the most special one’, Mary tells OC Media.

She remembers that as a child she used to go and play with the children in their district. Once, a boy she was playing with asked why she never went out with her brother. She felt ashamed to explain what was going on. But that was the one and only time Mary felt this way. When her parents started accepting Narek the way he was and made efforts to support him as much as possible, Mary began to appreciate Narek’s presence in her life.

‘Covid contributed to our relationship growing’, Mary says, laughing.

‘We had to stay home, and I discovered a lot of hidden things about Narek. For example, how caring he was, how much we love listening to music and dancing together, and the enthusiasm he has when I say we’re making a reel for TikTok. We became very close’.

Mary mentions that she used to sometimes think she would never get married because she thought it would be better to stay and take care of Narek. Besides, she would ask herself, ‘Who is going to be that mature person who would accept my brother?’.

Yet in the end, Narek met Mary’s future husband before she did — he was Narek’s rehabilitation specialist.

‘We go for a walk with Narek three times a week. It’s like a plan, a ritual we enjoy a lot. Narek is fond of fast food, coffee, and walking. We love spending time together’, Mary says.

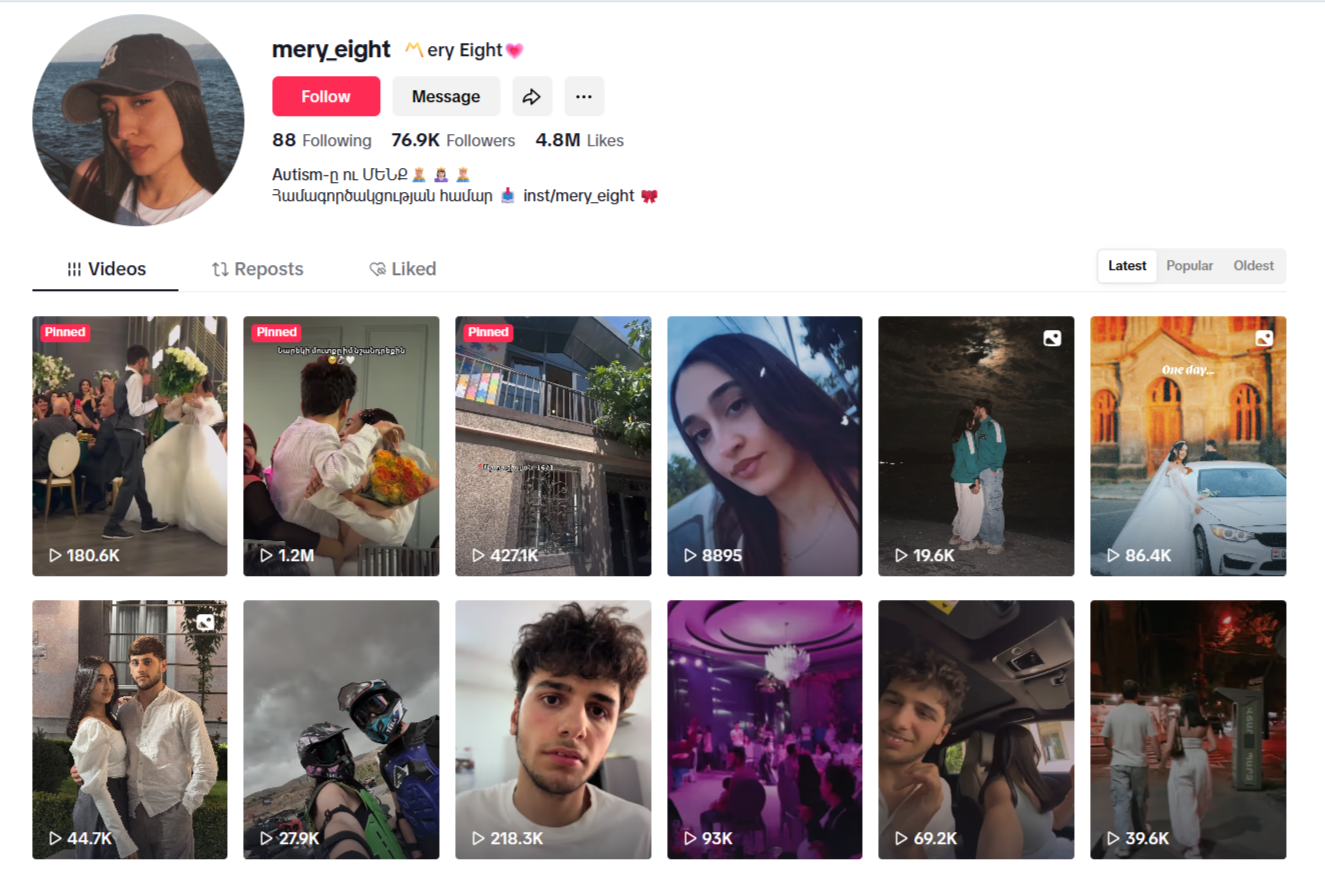

She also shares a TikTok page with Narek where they show their daily routines — the page has over 75,000 followers.

Not everything is smooth sailing, however.

‘Sometimes it’s challenging, because my brother may suddenly scream in the street. The other day, a woman saw Narek and acted impolitely. Usually, I don’t say anything, but at some point, you’re tired of people’s attitudes. I explained to her that my brother has autism and she can’t blame him for that. She left silently’, Mary says.

Systemic issues in education

Due to these perceived social difficulties, children with autism are often excluded from mainstream classrooms due to a lack of reasonable accommodations, support, and trained staff. Stereotypes, deeply rooted in society, are especially visible here — including assumptions about how a child should behave, what they should be able to do, and what constitutes the ‘correct’ way to communicate.

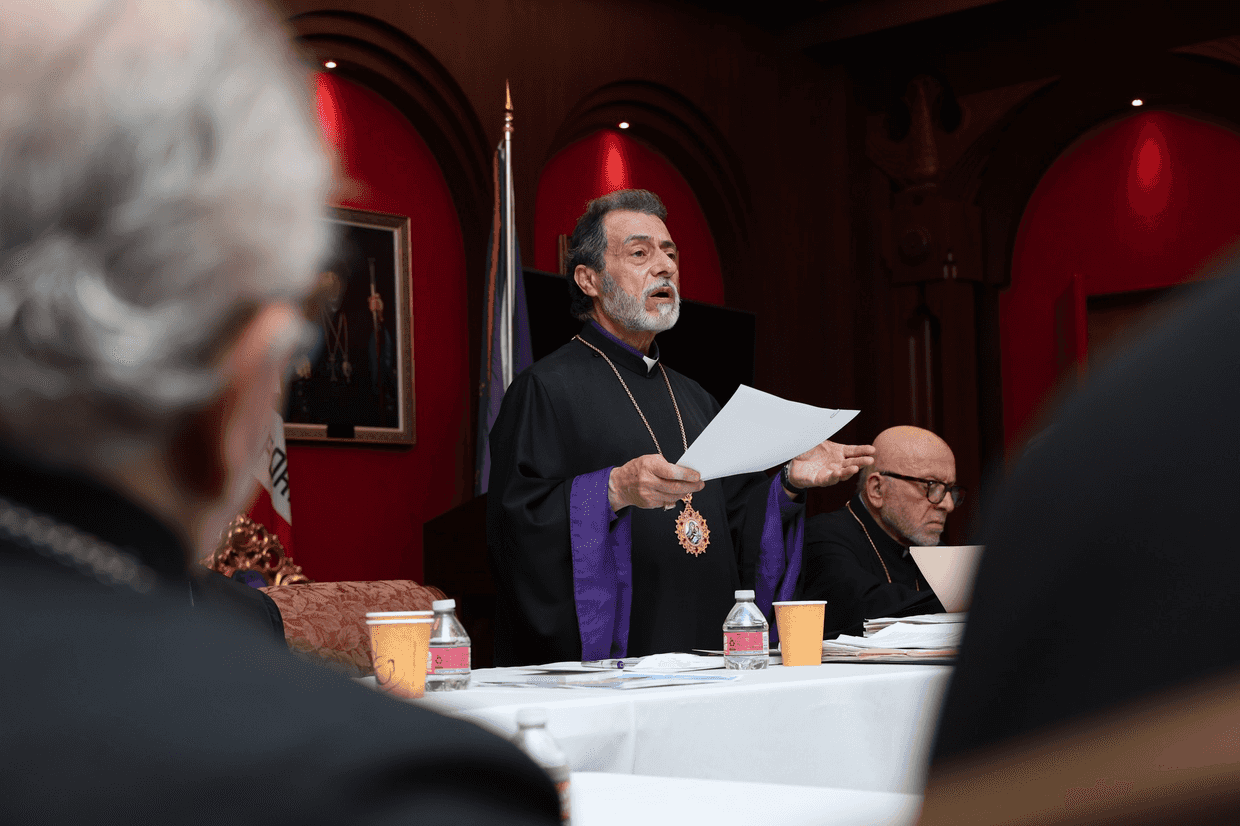

Mushegh Hovsepyan, president of the local Disability Rights Agenda organisation, emphasises that an accessible environment is essential.

‘For example, quiet rooms where children can have a calm space; light and sound control (noise reduction) in various settings — from classrooms to locker areas. The environment also needs to be safe’, Hovsepyan tells OC Media.

‘Meanwhile, we have an achievement regarding awareness. This is primarily the result of children learning side by side’, Hovsepyan says.

‘Another key development is the gradual decrease in cases where schools refused to admit children based on an autism diagnosis, instead recommending they attend special schools’, he continues.

Further changes came after the adoption of the Law on the Rights of Persons with Disabilities in 2021.

One such change was the recognition of the right to reasonable accommodation, which provides flexibility within the system when a student with autism has highly specific needs.

However, there are still challenges — such as the fact that there are limited opportunities for training, while those that do exist often focus on changing the child to fit societal expectations, rather than on accepting the individual and recognising human diversity.

‘For instance, a child may be taught not to flap their hands, to stop making certain sounds, or to suppress stimming behaviours that are actually helpful for self-regulation. This approach often prioritises conformity instead of true inclusion’, Hovsepyan says.

Another barrier is the lack of appropriate services within educational institutions for students who need human support throughout the day. For example, when a child requires the continuous support of another person, that role is unfortunately often taken on by the parents — which contradicts the principle of preparing the child for an independent life. In other cases, parents bear a financial burden by hiring an assistant themselves.

‘Overall, the inclusion of persons with disabilities is hindered by the absence of a flexible financial system. Schools are often unable to access specific services or supplies because existing systems are rigid and do not provide sufficient freedom. There is also a lack of coordination between educational and social services, which undermines the organisation of comprehensive support for children’, Hovsepyan says.

In many cases, the selection of special educators is driven not by professional qualifications, but by the need to fill a vacant position.

New initiatives for children with autism

There have been a number of positive changes to the educational environment for children with disabilities in Armenia since 2016. That year, inclusive education became a pivotal part of the system, and children with disabilities began to go to public schools.

Prior to that, however, it was hard. Narek, for example, went to school for only a couple of months, then he had to stay at home for two years. The family ended up finding a tutor who helped their son.

In 2016, Lena established the Teach Me More Development Centre to provide high-quality service to children with autism and to bring their parents together in one space.

Four years later, when Narek turned 16 and she realised he was not going to be able to find a job, she established the Teach Me More Soft Napkin production.

Today, three young adults with autism — Narek, Vazgen, and Narine — work there. While Narine is interested in making money to go shopping, Narek thinks about food, with all his money going to cafes.

Every one of Lena’s initiatives happened because of Narek, who has been her greatest inspiration.

‘We started [Teach Me More] with 18 children. Now we provide services to more than 500 children with autism per year. Recently, we established another rehabilitation centre where children with disabilities receive recovery and rehabilitation services through swimming. I went to Malaysia, took a special training course on swimming, then came back to Armenia and taught our specialists’, Lena says.

‘We never felt ashamed of him’

In Armenia, society continues to hold stereotypical attitudes towards disability — particularly around autism, intellectual disabilities, and mental health conditions. In rural areas, where recruiting teachers or specialist care can prove challenging, the situation can be even more difficult. Some regions have gone years without being able to hire specialists with the necessary expertise.

In small communities, there is also a reluctance to speak openly about problems or express needs. These issues are still often seen as ‘shameful’ or too personal to be discussed publicly.

‘Children with autism are sometimes misunderstood and labeled as “unsociable”, “lazy”, or similar terms. Yet their needs are different — they simply need to be identified and supported in the right way’, Hovsepyan says.

In 2023, Armine and her 14-year-old son Armen were displaced from Nagorno-Karabakh — their names have been changed to respect their privacy. After the displacement, the family of nine originally settled in a rural Armenian village. However, due to the lack of information and an accessible educational environment, the family was forced to move to Vagharshapat, a city close to Yerevan.

While Armen was diagnosed with autism when he was four-years-old, the family never applied for a disability certificate.

‘My husband said that people would start gossiping that our son had a syndrome. We were living in a small village. You know that not everything is easy there when it comes to disability. We never felt ashamed of him — he is such a clever and bright child. When we were displaced to Armenia, we still didn’t want to get this certificate, but then I said to my husband, “It is what it is, we need to proceed with the process” ’.

Hovsepyan highlights that parental acceptance and awareness is a very delicate issue. These situations need to be approached with sensitivity, as parents are often facing something entirely new and emotionally difficult. It’s their first time living through such an experience, making it hard to prepare for.

To mitigate these challenges, Hovsepyan says a constructive dialogue must be established with the parents.

‘Support professionals should provide answers to questions about autism, explain the diverse possibilities children have, and stress the importance of education. I also believe that creating peer support groups is essential. At this stage, many people feel like they are the only ones dealing with this issue. Just knowing that they’re not alone is already a form of support’, he says.

According to the Armenian Ministry of Labour and Social Affairs, there are currently 793 children with autism living in the country.

However, civil society groups believe the number is higher, in large part because some parents do not wish to accept that their child has autism and either do not get them tested or reject the diagnosis.

Hovsepyan highlights that the issue of data collection is a serious challenge — as it stands, the state does not have a clear understanding of its citizens or their needs.

While autism is not rare, in Armenia, more often than not, it is rarely understood. For true inclusion, experts say effort is required from both officials and the broader society to make understanding the norm rather than the exception.