In humid, lush, colourful Upper Adjara, wooden mosques nestle quietly into the green landscape, often indistinguishable from local homes. With no signposts or directions leading to them, these buildings often go unnoticed by outsiders — their minarets, often simple and modest, are the only indicators of their sacred function. Yet these structures are among the most unique and tangible remnants of Georgia’s Islamic heritage.

Located in southwest Georgia, bordering Turkey and the Black Sea, Adjara is an autonomous republic with a distinct cultural identity. Due to centuries of Ottoman influence, many highland villagers in Adjara practice Islam — a fact that has long set the region apart in a country where Orthodox Christianity dominates both religious and national narratives.

While Georgia formally presents itself as a multi-religious state, the Georgian Orthodox Church maintains a privileged status — legally, financially, and symbolically. Religious minorities, particularly in Adjara, continue to be sidelined.

Giorgi Rizhvadze, a researcher and activist from the town of Khulo, in upper Adjara, and a co-founder of the Solidarity Community, calls this the state’s ‘no-policy’ policy — a passive refusal to integrate or support ethnic and religious minorities.

‘There is no real will from the state to engage with Georgian Muslims’, Rizhvadze says. ‘Our existence is acknowledged only on a symbolic level, as if we’re a detail of the past. But we are part of Georgia’s present and future’.

Zooming out from Adjara, Georgia continues to struggle to embrace its full ethno-religious diversity. Despite official claims of pluralism, the idea of a ‘real’ Georgian is still largely tied to being ethnically Georgian and Orthodox Christian.

‘This narrow identity marginalises many communities’, Rizhvadze says.

As a way to work against this issue, activists have formed their own organisations, such as that of Rizhvadze’s Solidarity Community, a civil society organisation that was founded by a group of friends from Adjara. The group aims to raise awareness about Adjara, highlighting its cultural heritage, fostering social and civic engagement, supporting the self-organisation of the Muslim community, and promoting solidarity practices.

As of 2014, when the last official census to have its data published took place, Batumi’s Muslim population numbered over 145,000, making up 25.3% of the city’s total population. Despite this, the city still has only one mosque, built in the 19th century, which is too small.

‘Worshippers are forced to pray outside, in the rain or under the scorching sun’, Rizhvadze says. ‘It’s not just about prayer. It’s about dignity. About being treated as full citizens’.

Despite years of peaceful protests and legal battles, the construction of a second mosque continues to be blocked — a symbolic and tangible denial of rights.

‘We’ve followed the law, stayed peaceful, waited patiently — but we’re constantly met with silence or bureaucratic barriers. It shows a deeper fear in the political class: that accepting Georgian Muslims as equals somehow threatens national identity’, Rizhvadze says. ‘What this reveals is not just a lack of policy but a deeper challenge of national imagination. The journey toward becoming a truly inclusive, democratic society — one that acknowledges and respects its cultural, religious, and ethnic plurality.’

For Rizhvadze, this way of thinking is a form of historical erasure. While during the brief First Republic of Georgia (1918–1921), there was an effort to create an inclusive civic nation, Rishvadze says the Soviet invasion erased such progress, with the subsequent repression expunging the many contributions of Georgian Muslims.

‘Today, our stories are still missing from school textbooks and public discourse’, he says.

Disappearing heritage

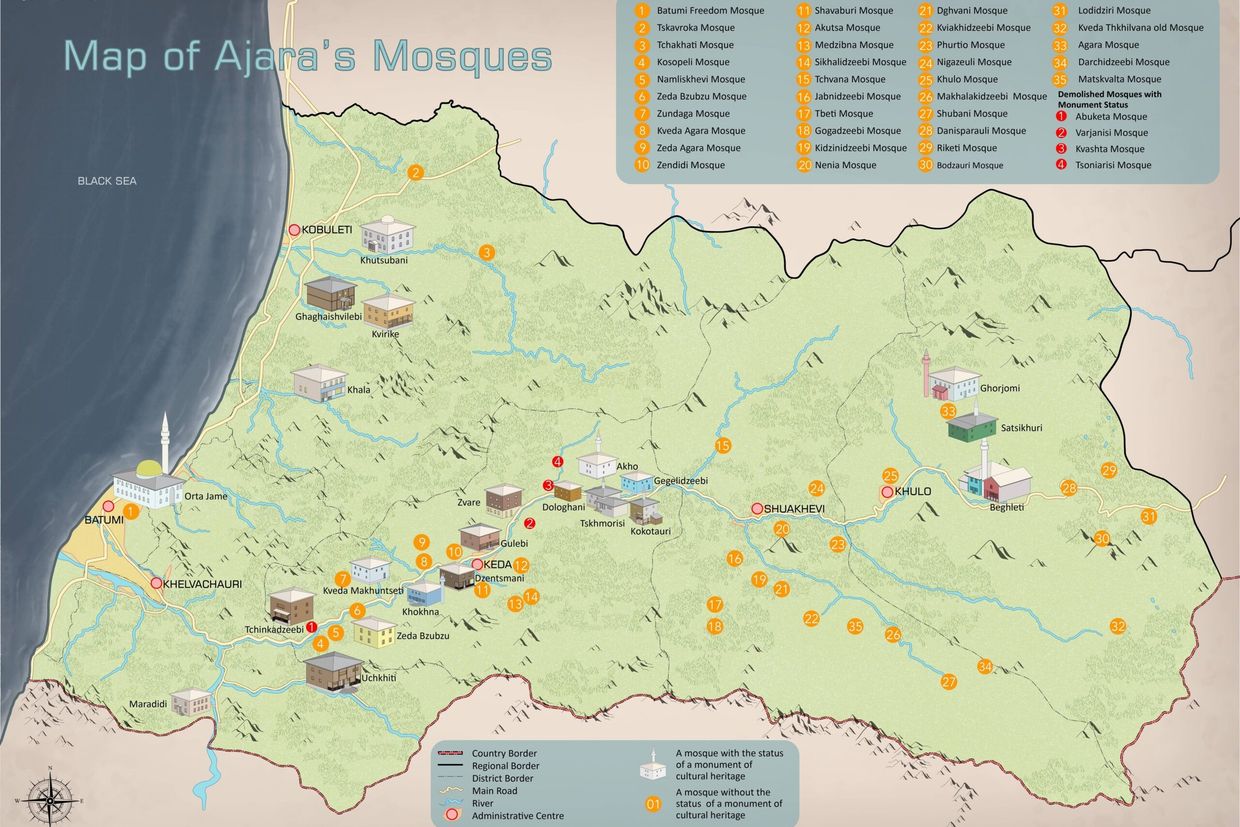

According to Indigenous Outsiders, a research project documenting endangered Islamic architecture in Georgia, over fifty wooden mosques built between 1817 and 1926 still stand in Upper Adjara. Some remain active spiritual and communal centres. Others are crumbling.

One of the most impressive is the Ghorjomi Mosque, the largest wooden mosque in the country. From the outside, it appears modest — plain silver-coloured corrugate hides its inner elegance. But inside, vibrant floral and geometric motifs swirl across the walls and ceiling, lovingly restored by local hands.

‘As Adjara has gone through different historical periods, so has this mosque’, Nuri, the mosque’s longtime muezzin, says. ‘During Soviet times, it became a cultural house. We watched plays and concerts here’.

Following Georgia’s independence, the community undertook to restore the mosque. Today, it is not only a place of prayer, but a social hub.

‘We collect money and food for those in need’, Nuri says. ‘This is about dignity, solidarity — not politics’.

Still, state support is minimal. As Nuri puts it: ‘Our survival depends entirely on our own people’s donations’.

A central question looms over these mosques: Do they belong to Georgia’s heritage or ‘others’, namely those of Turkish origin, whom nationalist voices often frame as foreign or threatening.

For researcher Kristine Mujiri, these debates are of no consequence as the form of the mosques — modelled after traditional Adjaran Oda houses — confirms their deeply local roots.

‘The resemblance is striking’, she says. ‘Open balconies, carved railings, sloped roofs — they are unmistakably part of Georgian vernacular architecture, just with an Islamic function’.

Nestan Ananidze, a civil activist and another co-founder of the Solidarity Community, agrees.

‘These mosques are artistic, communal, and architectural spaces that tell the story of who we are as Adjaran Muslims’, she says.

Beyond architecture

The Solidarity Community has been documenting Adjaran mosques and pushing for their official recognition as cultural landmarks since 2021.

In 2023, the group carried out a field study of 23 wooden mosques. The findings were grim: most were structurally vulnerable, lacking protection from rain, erosion, and time. Some had collapsed roofs; others were patched with plastic panels or peeling wallpaper. These sacred buildings were not listed as cultural heritage monuments, not marked for tourists, and not prioritised in any meaningful way.

For activists like Ananidze and Rizhvadze, the issue is bigger than buildings. It’s about belonging.

‘If the state recognised these mosques as national heritage monuments’, Ananidze argues, ‘it would also send a message: You matter. Your culture matters’.

Rizhvadze says that thanks to such efforts, more people now proudly identify as Georgian Muslims.

‘These are small steps — but they matter. They open hearts and minds’, he says.

He adds that stigma is slowly breaking down.

‘Before, people were ashamed or afraid to say they were Muslim. Now, more people, especially youngsters, speak openly. We’re seeing a new generation who say: I’m Georgian, and I’m Muslim — and I belong here’.

Even so, he says, the media still recycles the same narratives as years before.

‘They show these issues so superficially, there’s no real investigation or attempt to understand. People turn the page and learn nothing. That leaves room for fear and disinformation to grow’.

‘There are still elites in Georgia who view diversity as a threat’, he notes. ‘Ethnic and religious minorities are too often framed as potential agents of foreign interference — as if we don’t belong’.

According to him, what’s needed is not only policy change but a shift in mindset: ‘People need to stop fearing what is the fruit of previous centuries — that Islam is inherently foreign or hostile. These threats do not exist anymore. This is, first of all, the state’s responsibility. Now, we must build a democratic and open country together’.

Still, there are glimmers of hope. Hurie Abashidze, another co-founder of the Solidarity Community, shared that after years of pressure, the National Agency for Cultural Heritage Preservation of Georgia finally approved the tender for the restoration of the Zvare and Dzentsmani mosques.

‘The Dzentsmani mosque has already been demolished and is being rebuilt. I don't know yet what the final appearance will be, but the process is underway’, she says.

But progress remains uneven, and activists say more is needed.

‘The biggest problem is the lack of political will’, Rizhvadze emphasises again. ‘We can’t keep treating minorities with tokenism. If we want to be a democratic country, then everyone’s rights must be respected. A second mosque in Batumi would be more than a building — it would be a sign that Georgia is ready to embrace its diversity with real action, not just words’.

The deeper question, then, is not architectural — it’s political and ethical: ‘What kind of history does Georgia choose to protect?’ asks Ananidze. ‘Whose stories is it willing to tell?’

In the often-overlooked highlands of Adjara, wooden mosques still echo with prayers and community. They carry centuries of coexistence, art, and faith. Their future, however, hangs in the balance — a test of whether Georgia can embrace its full, diverse self.