After a series of controversial projects, Eagle Hills sets its sights on Georgia

The $6 billion Emirati investment project has stoked controversy in Georgia after the government decided to classify the details of the agreement.

On 21 October, the new Eagle Hills sales and showroom office officially opened on Tbilisi’s central Rustaveli Avenue — the same location where protesters have been demonstrating for nearly a year against the Georgian government’s EU U-turn and subsequent increasing repression.

It’s a curious choice of location: a protest zone lined with backpacking tourists snapping photos of Tbilisi’s mix of Soviet, modern, and Orthodox architecture.

Eagle Hills — founded by Mohamed Alabbar, chair of Emaar, one of the UAE’s largest real estate developers — first announced its $6 billion investment in Georgia back in January. Since then, the Georgian government has remained reserved about the details. Soon after the showroom’s grand opening, the government classified the full agreement, saying only that ‘the country’s interests remain fully protected’.

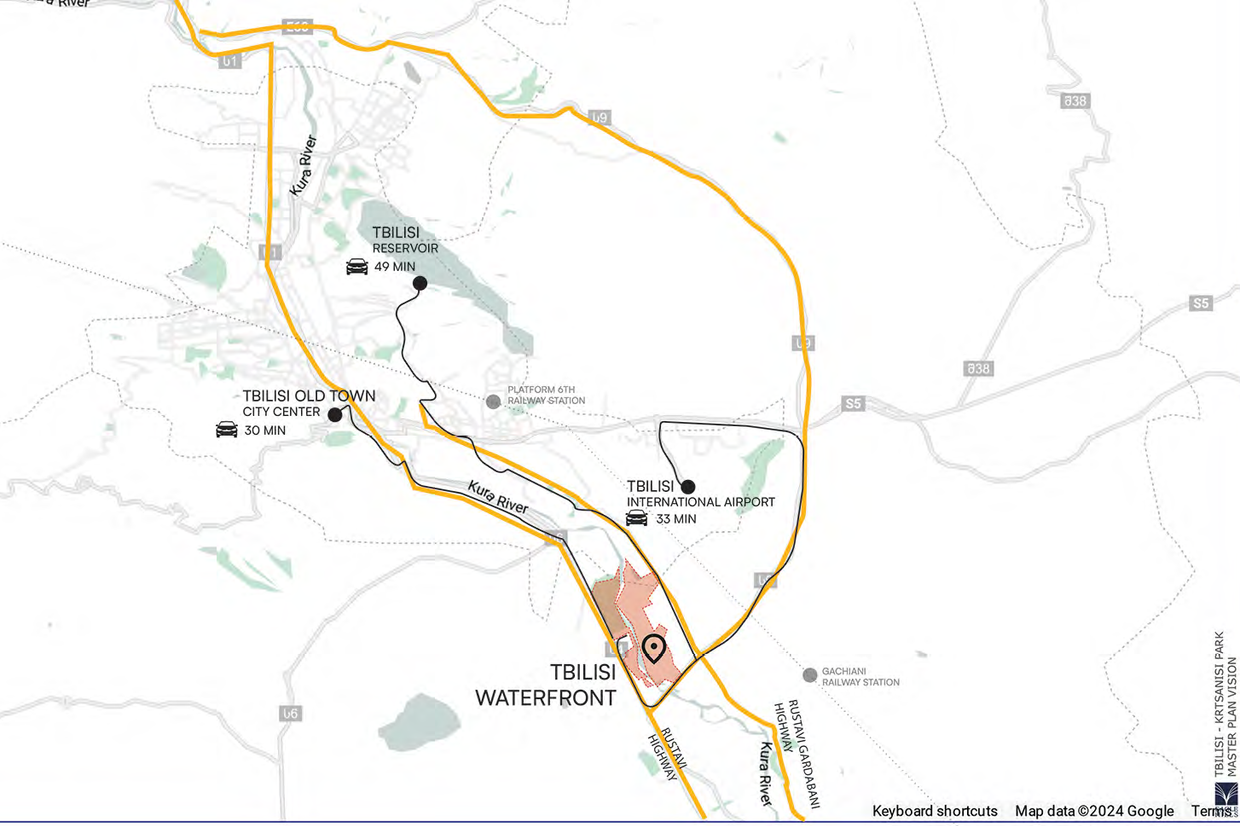

Responding to detailed written questions from OC Media, the Economy Ministry stated that ‘as a result of Eagle Hills’ unprecedented investment exceeding $6.5 billion, globally recognisable complexes will be developed in Tbilisi and Gonio, near Batumi’.

‘Both projects are multifunctional and include residential, hotel, commercial, office, recreational, and public spaces, with a yacht marina planned for Gonio’, the ministry said, adding that the projects will create more than 30,000 jobs and increase tourism by over 350,000 visitors annually.

The ministry also highlighted that Georgia would be a co-partner and co-owner (33%) in the project, which he claimed would bring long-term revenue into the national budget.

‘The project is entirely commercial, without tax or financial incentives, and aims to be mutually beneficial for both the state and the company’, the statement concluded.

Meanwhile, English and Russian-language advertisements have appeared online targeting wealthy investors — the companies behind the ads have not responded to inquiries.

It remains unclear why the showroom was opened in such a politically sensitive area rather than in one of the luxury developments such as Panorama Tbilisi, built by the country’s richest man and ruling party founder, Bidzina Ivanishvili. The timing also raises questions given Georgia’s history of failed megaprojects — such as the Anaklia Port and several hydroelectric projects — as well as a construction sector already struggling with labour shortages.

Economist Roman Gotsiridze, a former MP from the United National Movement Party (UNM), tells OC Media that thanks to former President Mikheil Saakashvili, who aimed to rapidly modernise the country, the first Emirati investment steps were allowed as early as 2006. By 2024, direct foreign investments from the UAE amounted to $1.2 billion.

Projects include Tbilisi Mall, the Sheraton Metekhi Palace Hotel (a $67 million investment with an additional $45 million spent on renovation), and The Biltmore Tbilisi, which cost $140 million. The Carrefour retail chain, another Emirati investment, now operates five hypermarkets and about sixty supermarkets throughout Georgia. The Poti Free Industrial Zone was originally established with Emirati investment, while several branded hotels in the seaside region of Adjara are also Emirati-owned. Terabank, with capital amounting to $120 million, is likewise owned by Emirati investors. One of the most recent projects, Dry Port, saw a $21 million first-phase investment, with a total value expected to reach $100 million.

The list is extensive — yet over the years, no one has expressed serious concerns about these projects. So why now?

According to Giorgi Kadagidze, the former head of Georgia’s National Bank, one of the bigger problems is that the government chose to classify the Eagle Hills deal, a decision he says is ‘nonsense’.

‘When Western investments stop coming in, every authoritarian regime runs eastward for “help”, where they sign opaque, dubious contracts. There are plenty of such examples — in Africa, Belarus, and Central Asia’, he tells OC Media.

Similarly, economist Nikoloz Shurghaia highlights that the figures listed by Georgian Prime Minister Irakli Kobakhidze at the opening of the Tbilisi showroom — namely that the project would entail $6.5 billion in direct investment to build — exceeds Georgia’s six-month national budget, thereby raising doubts about the project’s credibility and transparency.

‘The proposed 8.5 million m² land transfer is larger than several central Tbilisi districts combined. Limited information reveals major economic inconsistencies, absence of environmental and social risk studies, and no public consultation prior to signing — echoing the opaque Namakhvani HPP deal that caused billion-level losses’, Shurghaia wrote on social media.

He added that recent legislative changes allowing visa-free, long-term entry for citizens of certain poorer Asian and African countries who hold residency in wealthier Gulf states such as the UAE suggests that ‘thousands of foreign labourers may be brought in, affecting Georgia’s demographic balance’.

Eagle Hills has faced similar controversies in other states. In Serbia, the company’s Belgrade Waterfront project drew criticism for secrecy and the loss of public land to luxury developers. In Montenegro, its Velika Plaža beach leases sparked backlash over opaque procedures and the displacement of local businesses. In Hungary, the multibillion-euro Mini-Dubai project was abandoned amidst public opposition to non-transparent land sales. And in Albania, the $2.9 billion Durrës Marina was approved under disputed parliamentary conditions.

These recurring patterns — limited transparency, public land transfers, and governance concerns — have become trademarks of the company’s expansion model.

As another regional expert, who asked not to be named due to her work with Emirati investors, tells OC Media, these issues have all led the public to feel more wary.

‘What should be a success story — of a country in political backslide attracting major foreign investment — is instead a mystery. People are still guessing why billions are tied up in a deal whose terms remain secret’.