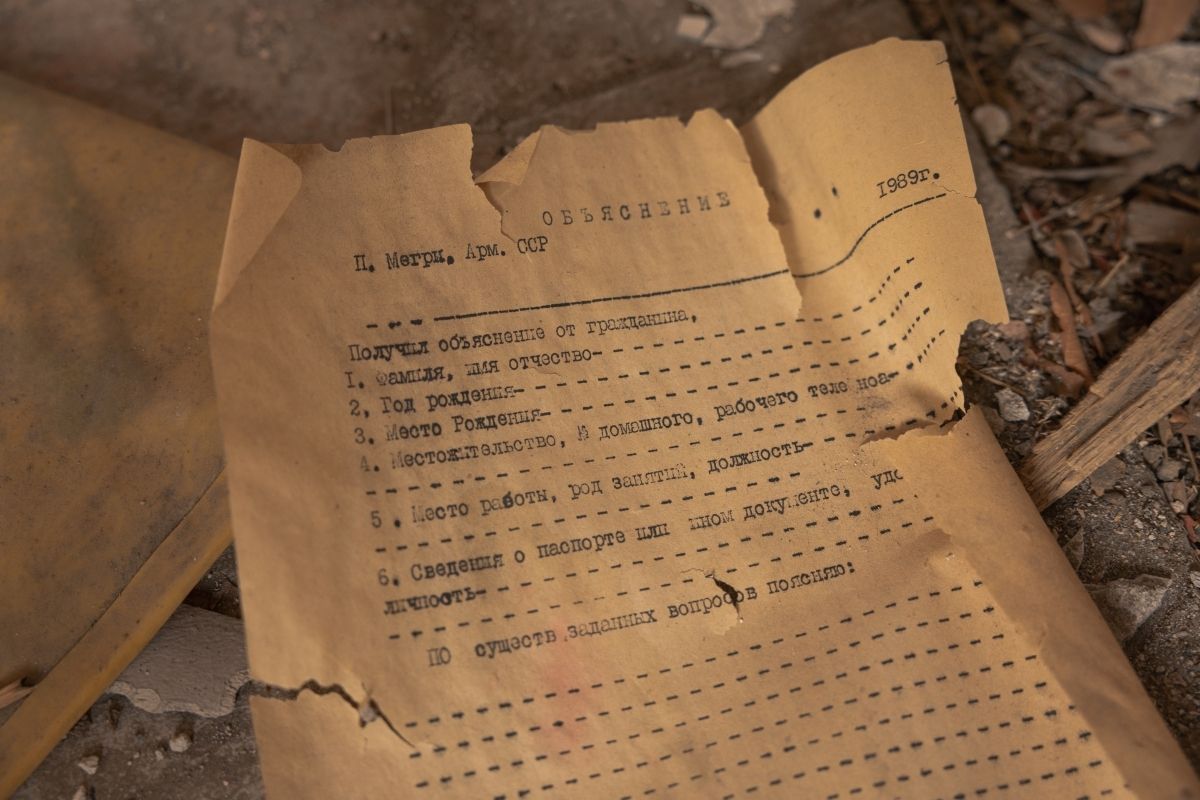

The Meghri railway station, nestled along the banks of the River Araks near Armenia’s southern border with Iran, is more than a decaying relic of Soviet-era infrastructure — it is a mirror reflecting the region’s complex and shifting geopolitical landscape.

Built during the Second World War, the railway was a crucial source of Armenia’s internal connectivity, linking Yerevan to the southern cities of Meghri and Kapan in just a few hours. But it has long since fallen into disuse. Its degradation is not just the result of neglect, it is a consequence of the unresolved regional tensions that continue to define Armenia’s borders and its future.

In 2023, Armenia announced an ambitious $1.2 billion plan to revive the Meghri railway, a section of the so-called ‘North-South corridor’ that would reconnect Armenia to Azerbaijan and potentially onward to Russia, Iran, and Turkey.

According to the plan, $1 billion would be invested by Azerbaijan and $200 million by Armenia. Armenia’s Economy Minister Vahan Kerobyan noted that the restoration of the Meghri segment would be particularly costly, as the old tracks had been completely dismantled and replaced by a road.

‘There may be a need for a new railway altogether’, Kerobyan said at the time.

‘The unblocking of [regional connections] is beneficial not only for Armenia but for the entire region’, Armenian Prime Minister Nikol Pashinyan said in 2023, emphasising that Armenia was ready to open all transport routes, provided its sovereignty and jurisdiction were respected.

But despite these proposals, the project never materialised. Instead, 2023 saw renewed tensions between Armenia and Azerbaijan, stalling diplomatic progress and raising serious questions about the viability of regional integration.

That September, Azerbaijan launched its last large-scale military offensive on Nagorno-Karabakh — by the end, the region was under the full control of Azerbaijan and almost the entire Armenian population, over 100,000 people, had fled their homes.

Subsequently, the topic of the so-called ‘Zangezur corridor’, an Azerbaijani demand for control of a strip of land through Armenia to link mainland Azerbaijan to its exclave of Nakhchivan, came to the forefront of negotiations between Armenia and Azerbaijan.

The perceptions of this route in Armenia and Azerbaijan have differed, if not been outright contradictory.

Pashinyan has continued to advocate for the unblocking of regional transport and infrastructure connections, including stressing that Armenia supports the principle of reciprocity in the reopening of rail and road links, including in regards to a route that would run through southern Armenia via Meghri to connect mainland Azerbaijan to its exclave, Nakhchivan. In turn, Armenian President Vahagn Khachaturyan, who is rarely seen in public, visited the Syunik province in late July, during which he proposed an ‘alternative’ name for the ‘Zangezur corridor’ — Gates of Syunik — which, according to him, would open up great opportunities for development for Armenia.

However, no matter the route chosen, the Armenian authorities have insisted that everything should be in accordance with international norms, the logic of Armenia’s sovereignty, and that Armenian border guards should be there.

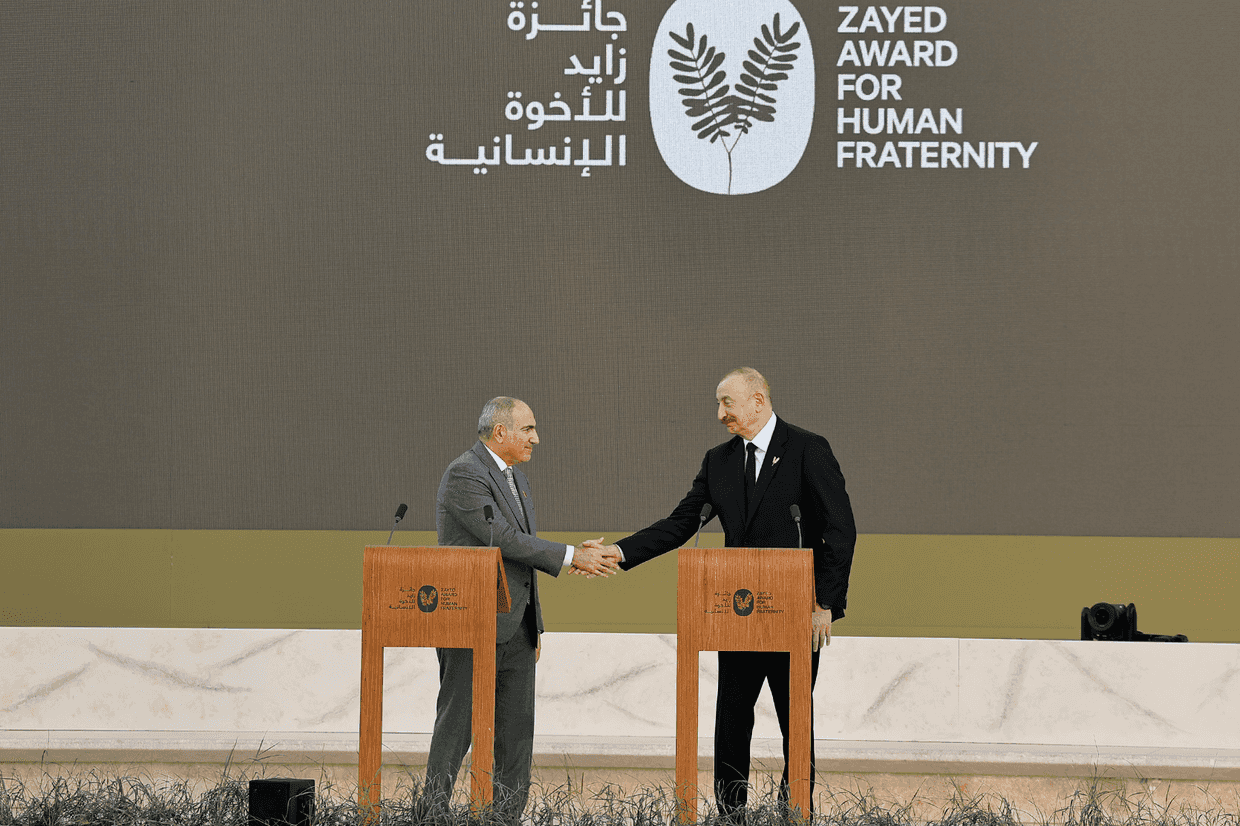

In contrast, Azerbaijani President Ilham Aliyev has clearly stated that infrastructure passing through southern Armenia was built by Azerbaijan and that Azerbaijani citizens passing through it should not see the faces of Armenian border guards.

‘We remember very well how in the Soviet years they stoned Azerbaijani cars when they passed through that section’, Aliyev said on 19 July.

Beyond the political arena, these competing visions have faced significant resistance from the general populace, particularly from nationalist voices who see such infrastructure projects not as economic opportunities but as threats to territorial integrity.

For many Armenians, the term ‘corridor’, as used by Azerbaijani officials, evokes fears of losing control over sovereign land, particularly as Azerbaijan demands unobstructed access through Syunik without Armenian customs or border controls.

On 8 August, discussions on the route appeared to be resolved with the announcement during the trilateral meeting between Aliyev–Pashinyan–Trump in Washington that ‘Armenia will work with the US and mutually determined third parties, to set forth a framework for the “Trump Route for International Peace and Prosperity” (TRIPP) connectivity project in the territory of the Republic of Armenia’.

‘These efforts are to include unimpeded connectivity between the main part of the Republic of Azerbaijan and [its exclave Nakhchivan] through the territory of the Republic of Armenia with reciprocal benefits for international and intra-state connectivity for the Republic of Armenia’, the signed declaration continued.

However, no concrete details have been released as of publication regarding the exact location of the route, how it will be managed, and by whom (beyond that it will reportedly be a US–Armenian company), leaving considerable uncertainty about how the project will play out in practice.

The impact that the project will have on the Meghri railway, the surrounding nature, and those who live in the area, is also unknown.

In the meantime, extensive road construction is underway in Syunik, notably involving two Iranian companies underscoring Iran’s increasing economic footprint in southern Armenia. Flights between Yerevan and Kapan now serve as the fastest alternative to travel, but capacity is limited to a 19-passenger plane. Meanwhile, the highway remains the dominant and most strategically significant mode of transport, vulnerable to shifts in regional power dynamics.

At the same time, Azerbaijan is laying the railway tracks towards Meghri while the Armenian side remains quiet. Indeed, in Meghri, the rusty wagons stand so silently that it is hard to believe they ever moved at all.

Yet, as the discussions surrounding regional transport routes demonstrate, the Meghri railway is not just a story of rust and abandonment. It is a story of power, diplomacy, and the fragile hope for regional cooperation in a landscape shaped by unresolved conflict and competing geopolitical interests.

As Armenia balances its relationships with Iran, Russia, and the West, and as Azerbaijan pushes for greater control over regional transit, Meghri remains a critical and contested crossroads.