Leyla and Imdad were only children when the First Nagorno-Karabakh War broke out, in part one of this multi-part series on the lives of Azerbaijani IDPs, they tell the stories of their displacement and survival.

With the collapse of the Soviet Union in 1991, armed conflicts in the Caucasus have resulted in more than 2 million refugees and IDPs across the region — with reverberations of these conflicts, displacing more people still. The latest tragedy, the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, initially led to the displacement of roughly 130,000 people.

Although the war is over and some have managed to return home after the Russia-brokered tripartite peace agreement in November, there are many more that impatiently await their stories of displacement to be over. Some of whom have waited for nearly 30 years.

After Azerbaijan’s victory in the war, a discussion has opened up about the future of the over 700,000 Azerbaijani IDPs displaced by the First Nagorno Karabakh War and whose life has been, in the words of one IDP ‘utterly dark’.

But behind the darkness, the stories of these people are also filled with virtue, and a remarkable will to survive even in the harshest circumstances. In the first of this multi-part series, we explore the stories of two Azerbaijani IDP families as the peace they had known all their lives turned into a brutal fratricidal war.

In future installments, we will follow these two families through their experiences as IDPs in Azerbaijan, and explore what the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War may mean for their future.

The war begins – Leyla’s story

Leyla Jahangirova was born in the village of Tugh, in Azerbaijan’s Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast, in 1984. The village had a mixed Armenian and Azerbaijani population that intermingled freely. Her parents spoke both Armenian and Azerbaijani fluently.

Now 37 and living in Baku, she recalls her childhood wistfully. How happy she and her siblings were to help their father wash his car by the river in the heat of the summer, the sound of the water as they splashed buckets of water on the car’s muddy tires.

She remembers hiking up into the mountains with her grandmother to pick herbs and sneaking out with friends to steal fruits drying on their neighbours’ roofs.

Above all, she remembers their house’s beautiful verandah, where her mother had a habit of throwing all the windows open as she played Demis Roussos’s song Goodbye My Love Goodbye on an old record player loud enough for the whole village to hear.

Those rosy memories came to an end in 1988. That year, unrest erupted amidst the turmoil surrounding the Armenian-led Karabakh Movement, which called on the Soviet government to transfer the majority ethnic Armenian NKAO from Soviet Azerbaijan to Soviet Armenia.

At first rumours of violence, and even murders, between Armenians and Azerbaijanis, reached the village. Tensions began to grow between neighbours. Clashes in the village followed shortly thereafter, an unknown assailant even fired a few rounds at Leyla’s grandfather’s farmhouse.

At first, Leyla’s parents couldn’t believe what was happening, even as their neighbours grew more and more concerned, they were certain there would not be war. ‘The Armenians would never really shoot at us’, her father would confidently refrain.

But the violence continued. ‘There was a little girl at the age of 8 in our village whose cousin was stabbed in front of her eyes’, Leyla said, the stabbing happened during a fight between schoolchildren.

Despite the worsening situation. Leyla’s father was adamant that they stay in Tugh. Every once in a while, their windows would be broken — and her father would dutifully change them, even as their neighbours would poke fun at him, that the war had started, and fragile new windows were not going to last very long.

But, in 1991 even Leyla’s father’s hope for peace reached a breaking point. As fighting in Nagorno-Karabakh intensified, Armenian forces had begun taking control of nearby villages — and violently expelling their Azerbaijani inhabitants. On 30 October, shells began to land in Tugh as Armenian forces advanced on the village and Leyla’s family finally decided to flee.

Her father locked all the doors — he expected to return.

On their way out — Leyla’s father decided to turn back. He was a doctor, what if other Azerbaijani residents, those who were elderly or disabled, needed evacuation? When he returned, he saw that much of the village was on fire. His home, somehow, had escaped the carnage, he retrieved only an audio recorder and a photo album.

On his way out of his home village, in a forest nearby, he stumbled upon an injured man hiding in the trees and helped drag him to safety.

The family was reunited in the nearby region of Fizuli. Despite the horrors of what happened to them and the horrors they feared were yet to come, as doctors, Leyla’s parents wanted to remain close to the fighting and help how they could.

A pair of shoes – Imdad’s story

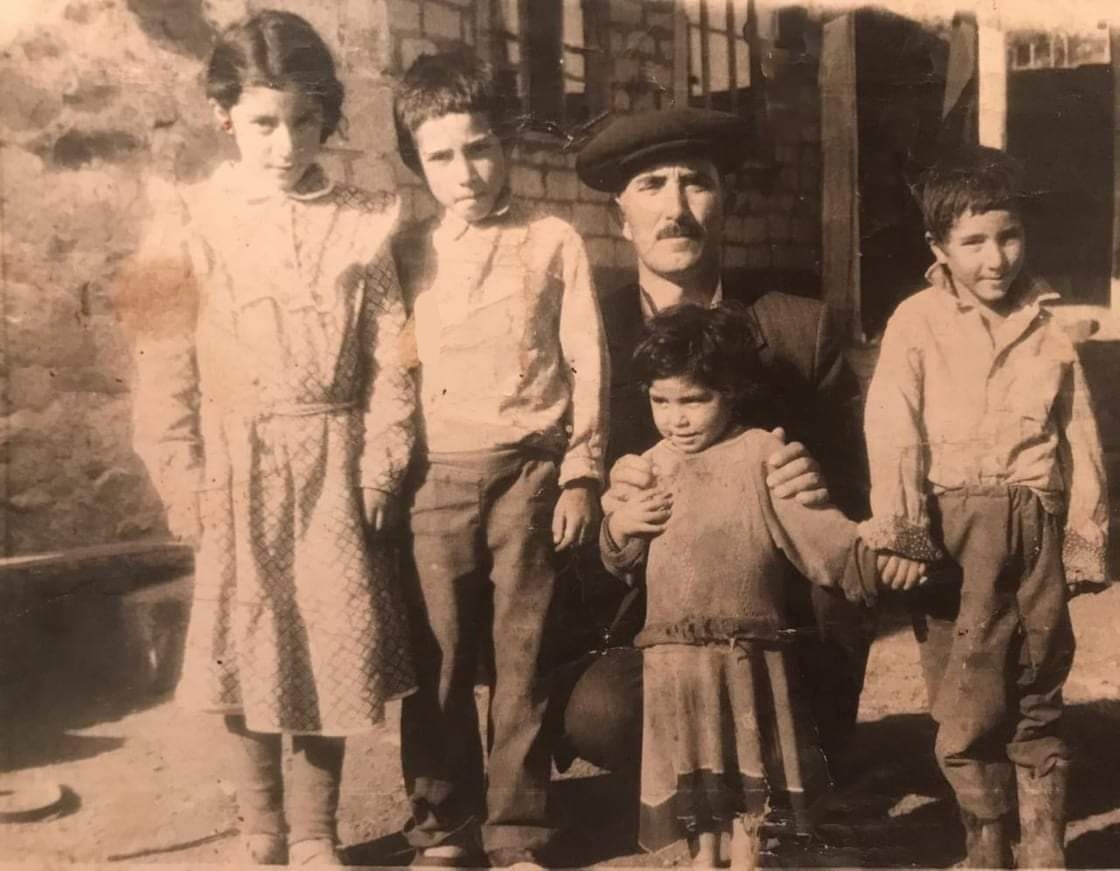

Left to right: Turaj Alizade (sister), Imdad Alizade, Ali Aliyev (father), Rahma Alizade (sister), and Babak Alizade (brother)

Imdad Alizade was born in 1980 in Oghuldere, a small village in Azerbaijan’s Lachin district located between the Nagorno-Karabakh Autonomous Oblast and the Republic of Armenia.

His father was a teacher and his mother was a housewife. Until the war, they lived a quiet provincial existence, supplementing their families’ income by tending to crops.

They all became IDPs in 1992 when Imdad was only 13 years old.

That year, his family had lived under a darkening cloud of anxiety. The Nagorno-Karabakh conflict had raged for three years already, and Azerbaijan was losing.

In February, Armenian forces had captured the town of Khojaly, in the aftermath of the capture hundreds of fleeing Azerbaijani civilians were killed. Then on 9 May, Shusha, the largest majority-Azerbaijani town in the NKAO, was captured by Armenian forces.

Within two weeks, Armenian forces had advanced to the West and taken the town of Lachin, the capital of the Lachin district. Fearing the same fate as the civilians of Khojaly, Imdad’s family decided to flee.

‘My family was divided into quarters’, he recalled. ‘My father and five siblings went one way, my grandmother the other way, I was taken to Barda, and my mother walked for 15 days over snowy mountains to bring the cattle’.

The family only reunited a month later and set up camp at the base of the Murovdagh mountains to the north of Oghuldere waiting for the Azerbaijani army to retake their village. They did not have to wait long.

In June, the Azerbaijani military undertook a massive offensive, retaking control of wide swathes of territory, including Oghuldere. The Alizade family returned home.

It was a painful homecoming. Basic infrastructure, like roads, water, and gas had been badly damaged by the ongoing fighting — which raged just a few scant kilometres from the village.

Then, six months later, word came that the Azerbaijani army had left Lachin. They had gone north, to the region of Kalbajar, to try to repel an Armenian offensive.

On 31 March, the family packed up, and went north, following in the footsteps of the army. There were not enough cars for all the residents of the village. ‘My brothers, who were 11 and 13, and our neighbour who had babies, two and four years old, we all had to leave by foot and walk’, Imdad said.

His father, meanwhile, stayed behind.

But when they had crossed over the first mountain and descended down into Kalbajar, they found a vast emptiness. The residents of the region fled as Armenian forces began closing in, and now, only cattle were left.

For days they wandered, winding through one abandoned village after another, scavenging supplies when they could, and keeping track of the news through a small radio. On the fourth day, they picked up a broadcast amidst the static: Armenian forces had just taken control of a key tunnel in Kalbajar. They were trapped.

If they were to escape, they had no choice but to head even further north and take the rugged mountain paths over the Murovdagh mountains, the highest mountain range in the lesser Caucasus.

They decided to abandon their cattle, much of their clothing, personal belongings, and food. All but their most prized possessions.

‘I managed to hide a pair of shoes that my father bought for me in Ganja’, Imdad remembered. But after four days of climbing mountain paths, I found out that I had lost one of them on the way’.

The hike was excruciating, as the group, tired and having had no food for days, was forced to trek over snow and mud. The adults took turns carrying the children, who became too weak to keep walking.

‘My mother couldn’t go anymore because of the wounds to her feet. She lost her hope and told us to leave her before we all got killed’, Imdad said. To try to raise her spirits, the adolescent tried to lie to her telling her that they ‘were almost there’.

Near the end of the mountain crossing, the group came upon a still-inhabited village: Yanishag. They hoped to find food and rest, but it was not to be. Shortly after they arrived, shells began to rain down on the village.

They ran.

Outside the village, they were picked up by a military truck stuffed with IDPs from Yanishag as well as other IDPs. It brought them to the top of the mountain, where they found another truck that would finally bring them down the mountain range to safety.

The family settled for a while in the city of Terter. While they had found relative safety there was no word of Imdad’s father, for weeks they prayed for his safe return — though they did not know if he was even alive.

Then, 54 days after they fled their village, Imdad’s father arrived in Terter and the family was finally reunited.

Their stay in Terter was not to last, however. The city was shelled within months of the family’s arrival. In the scramble to flee the city, Imdad lost the second shoe his father had given him.

For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status.