Dancing fabrics and contested poetry: inside Georgia’s resilient animation scene

Georgian artists continue to demonstrate the medium’s capacity to spread joy, even amidst difficult political circumstances.

On a hot day in early September, a crowd of spectators take their seats inside a monastery complex in the central Georgian village of Zemo Nikozi. A few hundred metres north lies South Ossetia, and during the 2008 August War the complex saw heavy bombing. But today the mood is bright — it is the second day of the Nikozi International Animation Film Festival, and for the rest of the week, the site’s stone episcopal palace will host screenings of animated films from around the world. This particular day is dedicated to the domestic offerings of the Georgian Animation Association (SAQANIMA).

Welcoming the visitors is the festival’s creator and host, the Georgian Orthodox Metropolitan of the surrounding region, Isaiah (born Zurab Tchanturia). The bishop was once an animator himself, but tough conditions for filmmakers in the 1990s led him to take a different path and join the clergy.

‘I quit animation when I enjoyed it the most’, he tells the crowd later on, speaking through a translator.

But the SAQANIMA programme makes clear that today, at least, the medium in Georgia is very much alive. Short films are shown from animators young and old, spanning a wide spectrum of abilities. All of them receive healthy applause, and the festival eschews any notion of competition; there are no prizes to be won, the event is one of pure celebration.

Closing the Georgian programme is an old highlight — its screening, we are told, is a rare treat. Dato Sikharulidze, who died in April, made the experimental animation film Ephemera in 1982. Long considered lost, it was recently recovered by the director’s family.

The film takes place in a tailor’s home workshop and begins in live action. As the tailor sleeps, two animated pieces of fabric join together in a hypnotic dance amid feverish visuals and an avant-garde soundtrack.

‘It was 1982, and to make such a film under the Soviet regime was so brave’, Mariam Kandelaki, a filmmaker and the founder of SAQANIMA, says when we speak a few days later at the organisation’s home in Tbilisi.

She describes how animators in Soviet Georgia had to conceive of a ‘special language’ that employed heavy use of metaphor.

In the 1980s, Sikharulidze had studied animation under Kandelaki’s father, the director Gela Kandelaki, in a workshop at the Shota Rustaveli Theatre and Film University that emphasised this style. Bishop Isaiah, who in Nikozi had expressed particular excitement at being able to rewatch the film, also studied there.

The location of the festival, so close to South Ossetia, is also no coincidence.

‘That’s the reason that we do this festival there’, Kandelaki says when I mention the proximity with South Ossetia. She argues that the festival, along with an art school for children established near the church with international backing, has helped Nikozi avoid the comparative exodus of residents that befell other communities near South Ossetia: ‘It’s very important for us to dedicate our time and energy for those who are there in this dangerous situation’.

And though the Georgian Orthodox Church has a less than progressive image in the country today, Kandelaki considers the festival’s figurehead an exception among his peers: ‘For me that’s the Orthodox religion […] to be open and to be kind and progressive’, she says of Bishop Isaiah.

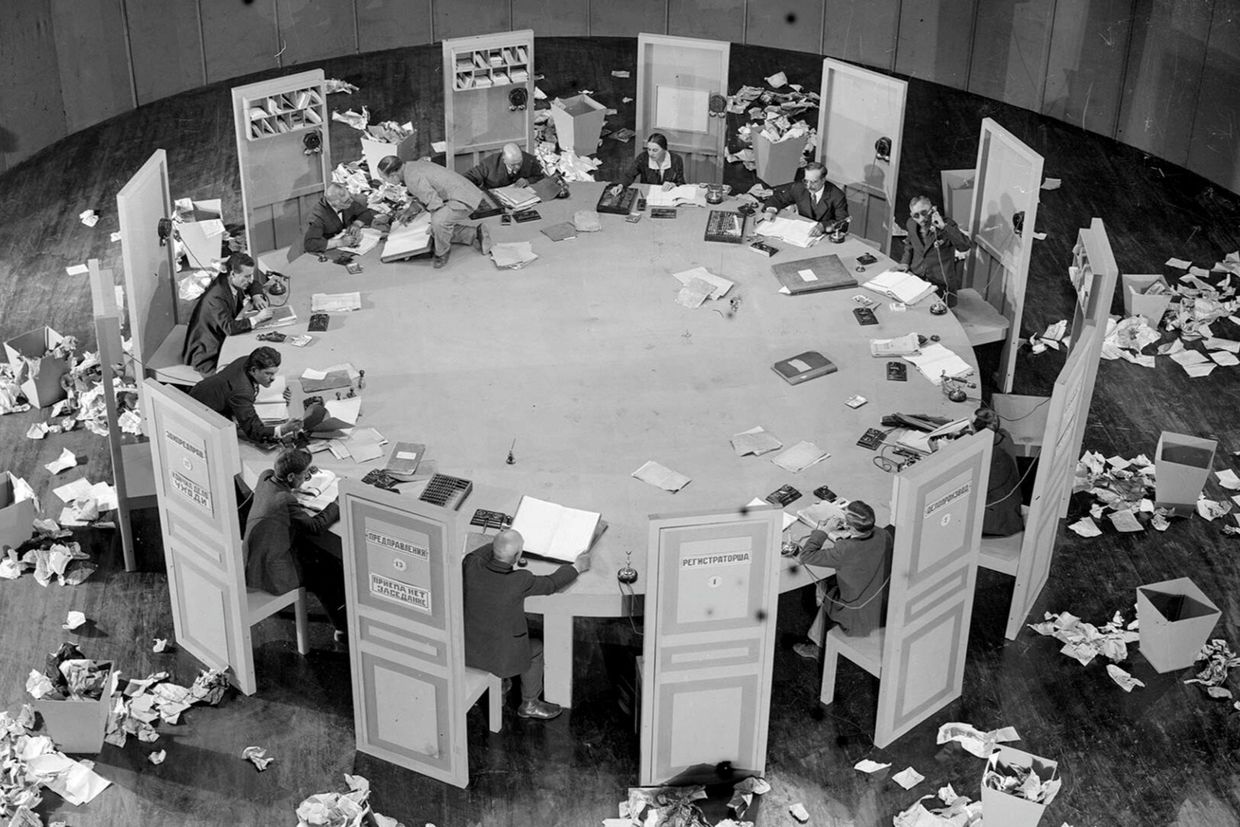

For Kandelaki, the history of Georgian animation stretches as far back as 1929, to the appearance of the silent film My Grandmother (directed by Kote Mikaberidze). That film employed a number of pioneering animation techniques in its parody of bureaucracy.

‘It was a commissioned work, but then it ended up being such a great satire about the system and the regime’, Kandelaki says. Mikaberidze’s film was shelved by Soviet censors.

‘Quiet resistance’ was a trait ascribed to Georgian animation by the Ottawa International Animation Festival while promoting their own recent programme from the country. Considering the transgressive content of these historical films, together with the very fact of the Nikozi festival’s existence, it seems a fair label.

Tbilisi’s new stop motion hub

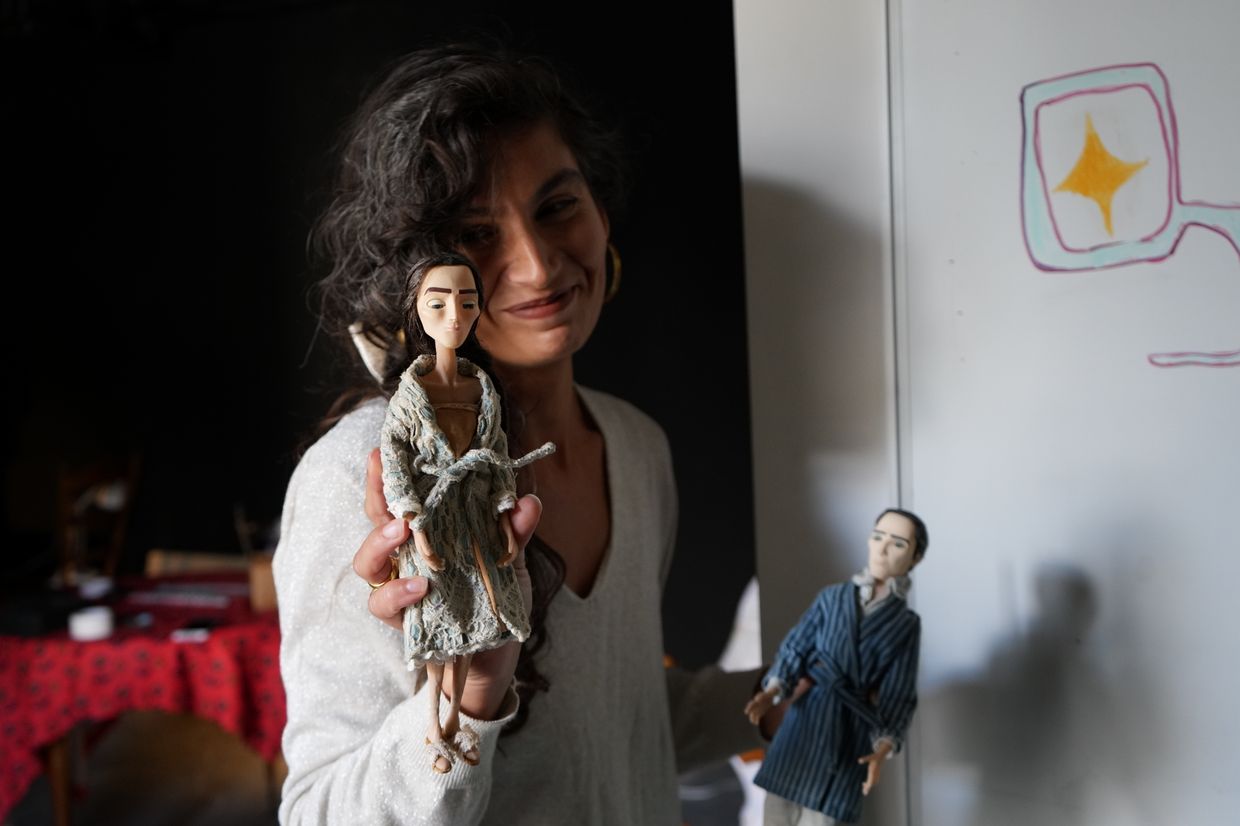

Of the recent efforts shown during the SAQANIMA programme, there is a clear standout: meticulously crafted in stop motion, Elene Dariani (2024, directed by Elene Tavadze), tackles the mystery surrounding the authorship of a cycle of erotic and romantic poems published under that name. Though traditionally thought to be a pseudonym employed by the famous symbolist poet Paolo Iashvili, the film engages with the alternate theory that ‘Elene Dariani’ was in fact a real woman, a lover of Paolo named Elene Bakradze.

In the 15-minute short, we follow Elene through the nighttime cobbled streets of early 20th century Tbilisi as she pens the love letters that inspire the poems, causing uproar among the prudish public. The closing image of Elene in bed with her husband while a black cat — a stand-in for Paolo — furtively nestles himself between the pair is testament to the film’s deft direction and elegantly rendered eroticism. This sophistication belies the fact that the work was a first attempt at stop-motion filmmaking by its creators.

At Fantasmagoria, the Tbilisi stop-motion studio behind the short, animators are hard at work on new projects; the studio’s support for young creatives is immediately clear. Lina Akulashvili, 23, has experience as an illustrator of children’s books, and the studio is helping her to translate those illustrations into the medium of animation. Salome Kalandarishvili, 25, is also working on bringing her physical artworks — made up of unconventionally textured watercolours — to the screen.

But the communal atmosphere is such that generational divides do not really figure: Kalandarishvili works alongside her animator mother, Khatuna Tatuashvili, and puppet maker Irakli Mizrakhi, 40, was trained in his craft by someone over 20 years his junior.

‘We have no ages here’, jokes Sofio Chincharauli, who produced Elene Dariani and co-founded the studio a few years ago with her best friend and the film’s director, Elene Tavadze.

The duo reveal some of the painstaking technical elements that went into that film’s creation, including a tray of a dozen 3D-printed facial masks for the character of Paolo (in human form this time).

‘We print every emotion that we need’, Chincharauli says.

Also on display are the film’s sets, intricate dioramas featuring tiny cognac bottles and typewriters.

The film was clearly a labour of love for them — and its origins were notably serendipitous.

Coincidentally, Chincharauli had just opened a restaurant in Tbilisi under the name Elene Dariani when Tavadze came across a book in the State Museum of Literature featuring Bakradze’s diaries, whose content could be traced back to the poems. After reading the book together, they decided to make the film.

Though the ultimate authorship of the poems remains an open question, the pair feel that, whether or not Iashvili polished off the final cycle, at the heart of the poems are ‘female passions’, as Tavadze puts it.

‘Every woman has a story like Elene Bakradze’, echoes Chincharauli, referring to the heroine’s experience of unconsummated love.

Despite positive reactions elsewhere, particularly from younger viewers, the film drew some ire on release from those who remained convinced the poems could only be Iashvili’s. One particular response in that vein, from then culture minister and prominent Georgian Dream MP Tea Tsulukiani, seemed to again drag Georgian animation into the political sphere.

Tsulukiani ‘hates Elene Bakradze’, Chincharauli says, ‘but we don't know why’.

The pair blame Tsulukiani for blocking a grant from the Georgian National Film Centre they were due to receive to pay for flights to France for the film's premiere last year.

‘Maybe it was some political grievance’, Tavadze suggests, though the pair can only speculate as to what exactly that may have been. In any case, as reported by RFE/RL’s Georgian service, Tsulukiani had previously condemned the book that inspired the film. She did so while welcoming the release of a second book purportedly reconfirming Iashvili as author of the cycle.

Despite this encounter with cultural conservatism, the studio continues to receive government funding from Tbilisi City Hall (as well as from the EU and NGOs). After all, the appeal of this art form is such that it can eclipse politics, as Mariam Kandelaki tells me. She recalls how a Tbilisi City Hall representative was able to bond with the French Ambassador during an animation workshop she hosted last year.

‘They were happy to talk to each other […] because animation is such a medium that everybody loves’, she says.

A perfect vehicle for staging that ‘quiet resistance’, then, should a filmmaker be so inclined.