International and local election observers often note violations of the secrecy of the ballot in Georgia, and the 2021 local elections were no exception. According to a recent study, a plurality of people think such violations could take place in Georgia, and some have heard of such cases in the past year.

On the survey on election-related attitudes carried out by CRRC Georgia for ISFED, respondents were asked about a hypothetical country where a citizen’s vote was somehow revealed to a neighbour who was on the election commission.

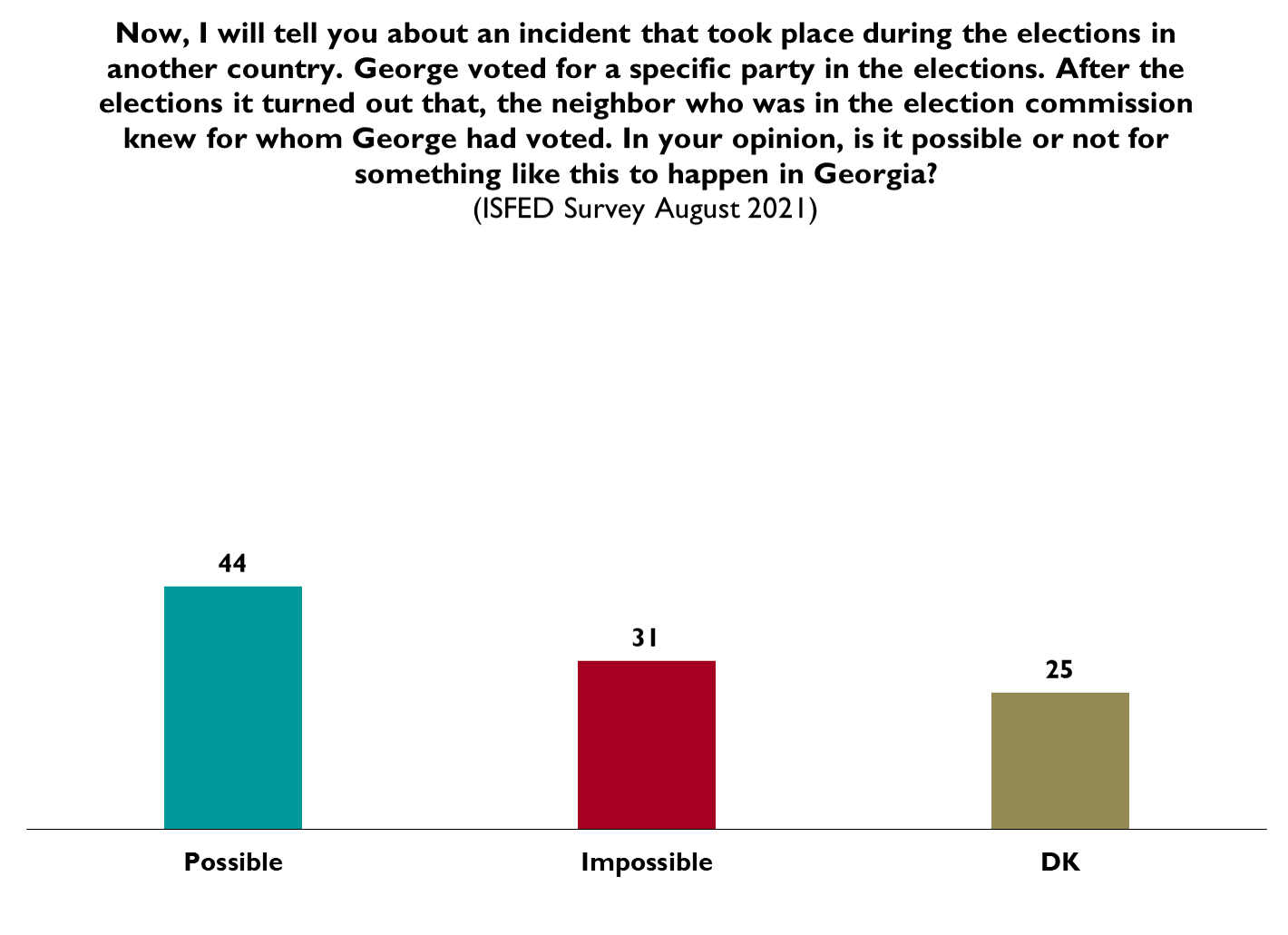

Respondents were asked if they thought that something like this could happen in Georgia. A plurality of respondents thought it was possible, while around a third deemed it impossible. The rest were unsure.

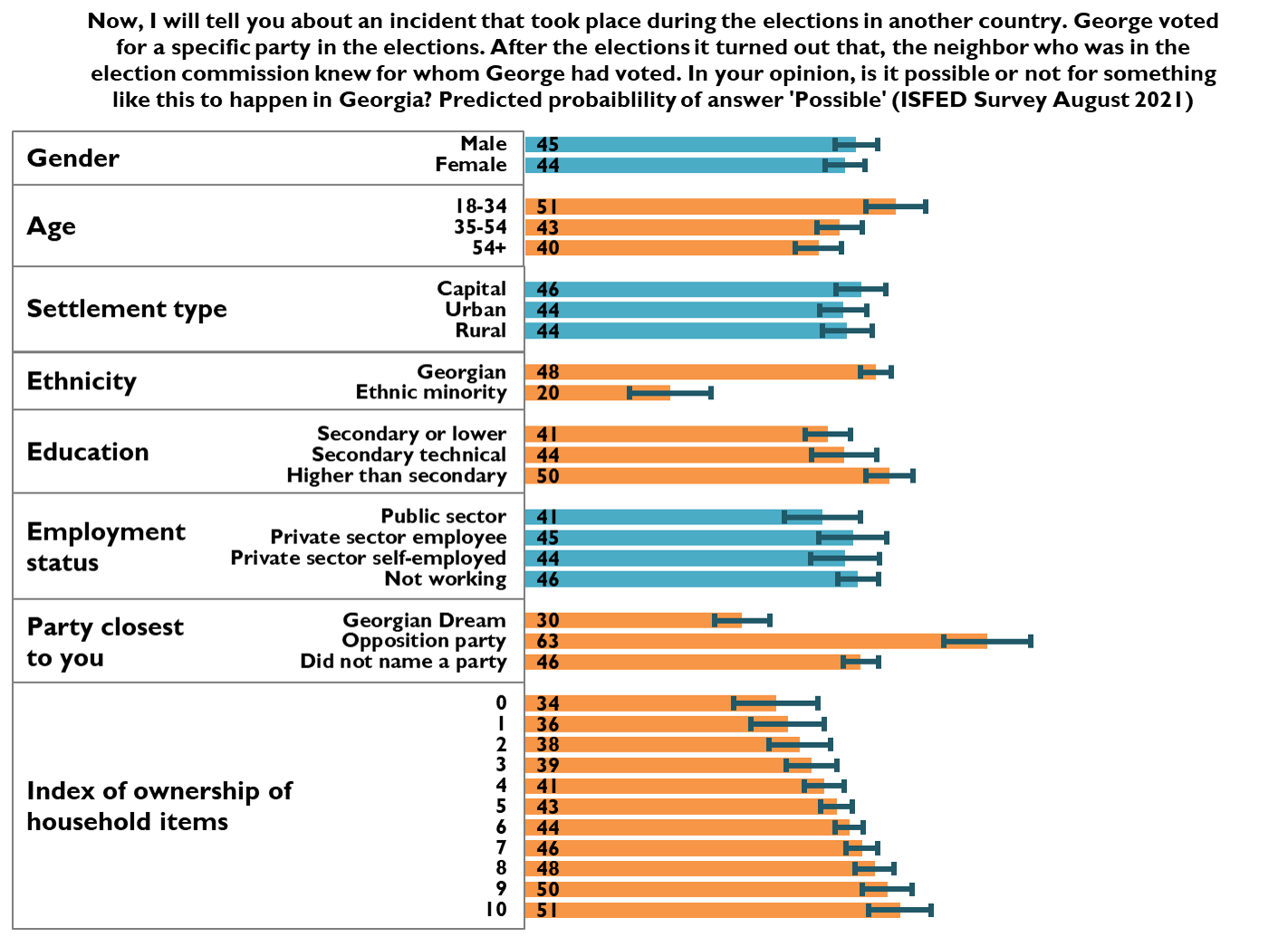

A regression analysis shows that people in the 18-34 age group were around 1.2 times more likely to think that someone else might find out who they voted for than older people.

Even though election observers recorded more violations of the secrecy of the ballot in areas predominantly populated by ethnic minorities, ethnic Georgians were 2.4 times more likely to think this kind of violation was possible in Georgia compared to ethnic minorities.

People with higher than secondary education were 1.2 times more likely to deem it possible than people with secondary or lower education.

The more durable goods a household owned (a proxy for wealth), the more likely a person was to think the secrecy of the ballot could be compromised in Georgia.

Opposition party supporters were 2.1 times more likely than Georgian Dream supporters and 1.4 times more likely than people who did not name any party as close to their views to think this was possible in Georgia.

There were no differences in terms of gender, settlement type, or employment type.

Note: This and the following chart were generated from a regression model. The model includes gender (male, female), age group (18–34, 35–54, 55+), settlement type (capital, urban, rural), ethnicity (Georgian, ethnic minority), education (secondary or lower, secondary technical, tertiary), employment status (public sector, private sector employee, self-employed, not employed), party respondent names as closest to his/her views (Georgian Dream, opposition party, did not name a party (Don’t know, Refuse to answer, No party)), and an additive index of ownership of different items, a common proxy for wealth.

In focus groups and in-depth interviews, some participants felt that the secrecy of the ballot could only be violated when a voter chooses to show someone their ballot or tell them who they voted for.

Some participants reported that party coordinators asked voters to send a picture of their ballot. Other participants indicated that voters might mark their ballot by drawing a line or putting a dot on it so that it is possible to tell who they voted for.

However, participants underlined this would still mean that the voter revealed their preferences.

One participant stated, ‘I have heard of many things, that they have told them to mark it in a specific way, put a cross on it or a dot. So I have heard of it, but not that they have forced someone. Such things happen. I don’t know. They talk about many things.’

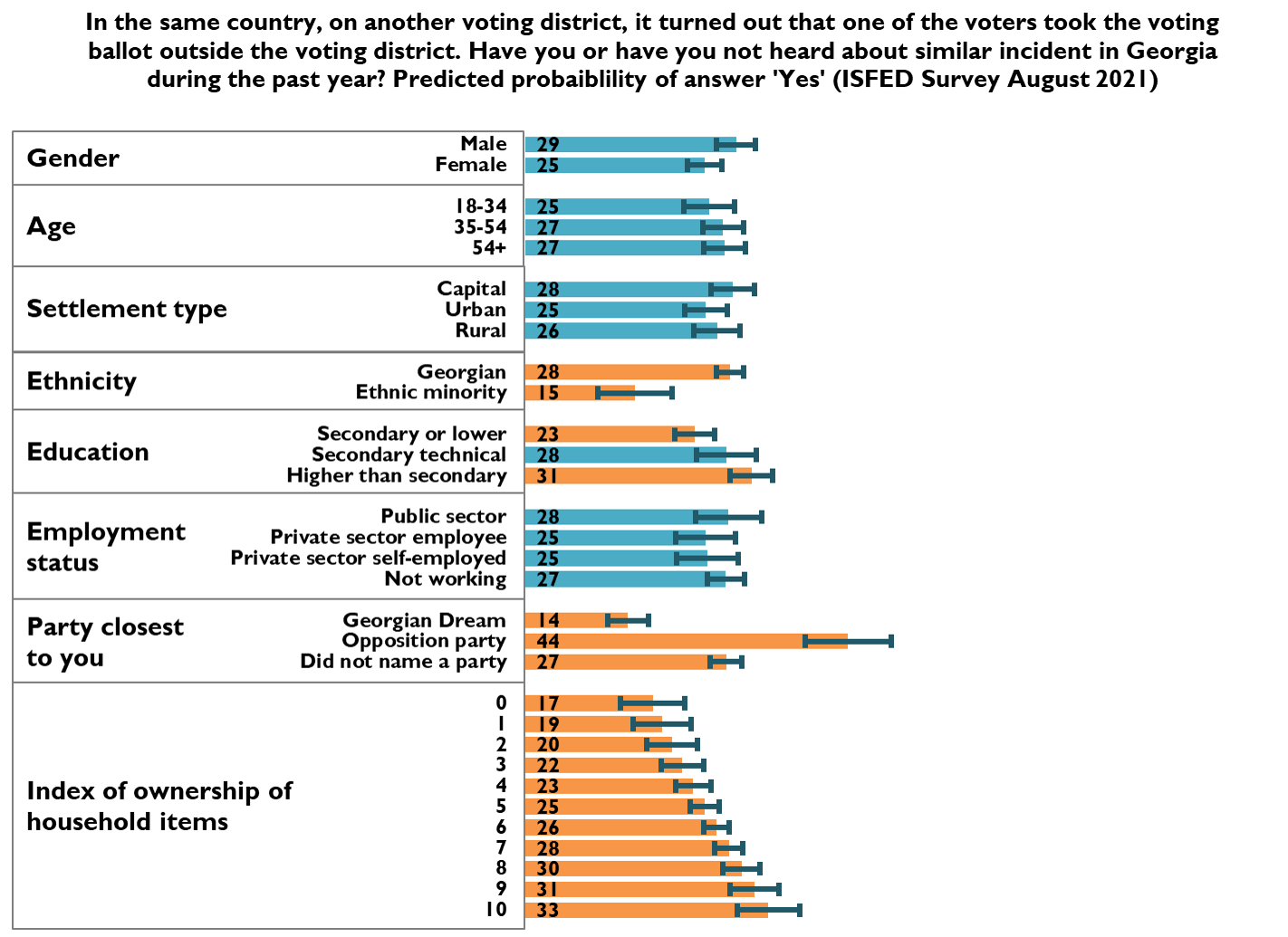

The survey shows that, in the past year, 27% of the population had heard of a voter taking their ballot outside the election precinct. Most of the population (61%) had not heard about such an incident.

A regression analysis shows that ethnic Georgians were 1.9 times more likely to report knowing of such cases than ethnic minorities.

Similarly, opposition party supporters were 3.1 times more likely than Georgian Dream supporters and 1.6 times more likely than people who did not name a party to report that they had heard of a ballot being taken out of an election precinct.

Wealthier people were also more likely to say they knew of such cases. There were no gender, age, settlement type, or employment-related differences in the data.

Regardless of whether they had heard of someone taking their ballot outside the election precinct, a majority (88%) of the population thought that it was unacceptable or completely unacceptable when a political party coordinator asks a voter to take a picture of their ballot. There were no differences between different groups on this issue.

Thus, a plurality of Georgia’s population thinks it is possible for someone to know who you voted for. Qualitative data suggests that the public thinks this only occurs if a voter reveals their vote to someone else.

For a majority, it is unacceptable to be asked to take a photo of one’s ballot. Young people, ethnic Georgians, people with higher than secondary education, opposition supporters and people with better economic situations were more likely to question whether the secrecy of the ballot is respected in Georgia.

The views presented in the article reflect those of the author alone, and do not reflect the views of ISFED, CRRC Georgia, or any related entity. The data used in this article are available here.