Georgian officials and those associated with them are increasingly using private lawsuits to conduct what critics claim are systemic public attacks on journalists and activists, and so silence their critics free from public scrutiny.

In May 2024, an investigation by opposition-leaning TV channel Pirveli claimed that a business group owned by the father of Georgia’s current ruling party chair and former prime minister, Irakli Garibashvili, had received a business contract that appeared aimed at laundering unexplained wealth through a French company.

A month later, Garibashvili’s family filed a lawsuit accusing the Pirveli media group of defamation.

In recent years, increasing numbers of Georgian activists, news outlet owners and managers, and journalists have been legally targeted for claims or reports that are critical of the government, suggesting these may be examples of SLAPP: strategic lawsuits against public participation.

Those who file lawsuits may not intend to simply win the cases, but also put financial and emotional pressure on the defendant, and send a warning signal to others who may be thinking about scrutinising those in power.

‘The defendant, which is often a civil society group or a media outlet in Georgia, has to spend excessive resources and [pay for] court expenses’, says Mariam Gabroshvili, a lawyer with the Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association (GYLA). ‘This effectively results in weakening a defendant, ultimately endangering freedom of expression.’

Government targets civil society

Civil activists and media workers are SLAPPs’ usual targets. However, unlike in Western democracies where corporations frequently go after activists, in Georgia, it has generally been governmental officials or those connected to them launching the lawsuits.

The Coalition Against SLAPPs in Europe (CASE) in 2023 confirmed that in Georgia, ‘most lawsuits are brought by politicians [and] high-ranking officials or affiliated persons against the media’.

According to the Georgian Democracy Initiative (GDI), a Tbilisi-based watchdog group, there are 43 ongoing defamation cases in Georgia’s courts that they consider SLAPPs, 39 of which are targeting local media groups or journalists.

GDI is spearheading a campaign to raise public awareness of the problem and provide legal assistance to the targets of SLAPPs in Georgia.

As GDI’s chair Eduard Marikashvili observes, a trend of officials or those associated with them being claimants in lawsuits against activists is often a hallmark of countries with authoritarian tendencies.

‘In terms of the level of involvement of the government in SLAPP cases, at this point, Georgia is really unique’, adds Marikashvili.

Undercover censorship

In February 2022, Georgia’s State Security Service (SSG) lashed out at UNM member Levan Khabeishviili, who alleged that the SSG and its chair, Grigol Liluashvili, were criminally connected to an international call centre scamming scheme based in Tbilisi.

While the SSG vowed to ‘appeal to all legal remedies’ in response, it was Liluashvili, the former CEO of the board of ruling party founder Bidzina Ivanishvili’s Cartu Group, who filed a lawsuit as a private citizen against the opposition politician as well as two TV companies.

In the case of claims against media, Georgian public officials have access to well-established media self-regulatory bodies and mechanisms, but instead resort to court proceedings. GDI focuses on whether a claimant resorted to self-regulatory tools before taking their case to court as a factor for deeming a lawsuit a SLAPP case.

GDI also stated that in most cases, the court was uninterested in whether media had offered the plaintiffs a chance to respond before airing the claims.

The cases also ignore the context in which media organisations are operating, with the government and ruling party increasingly criticising and curtailing press freedoms.

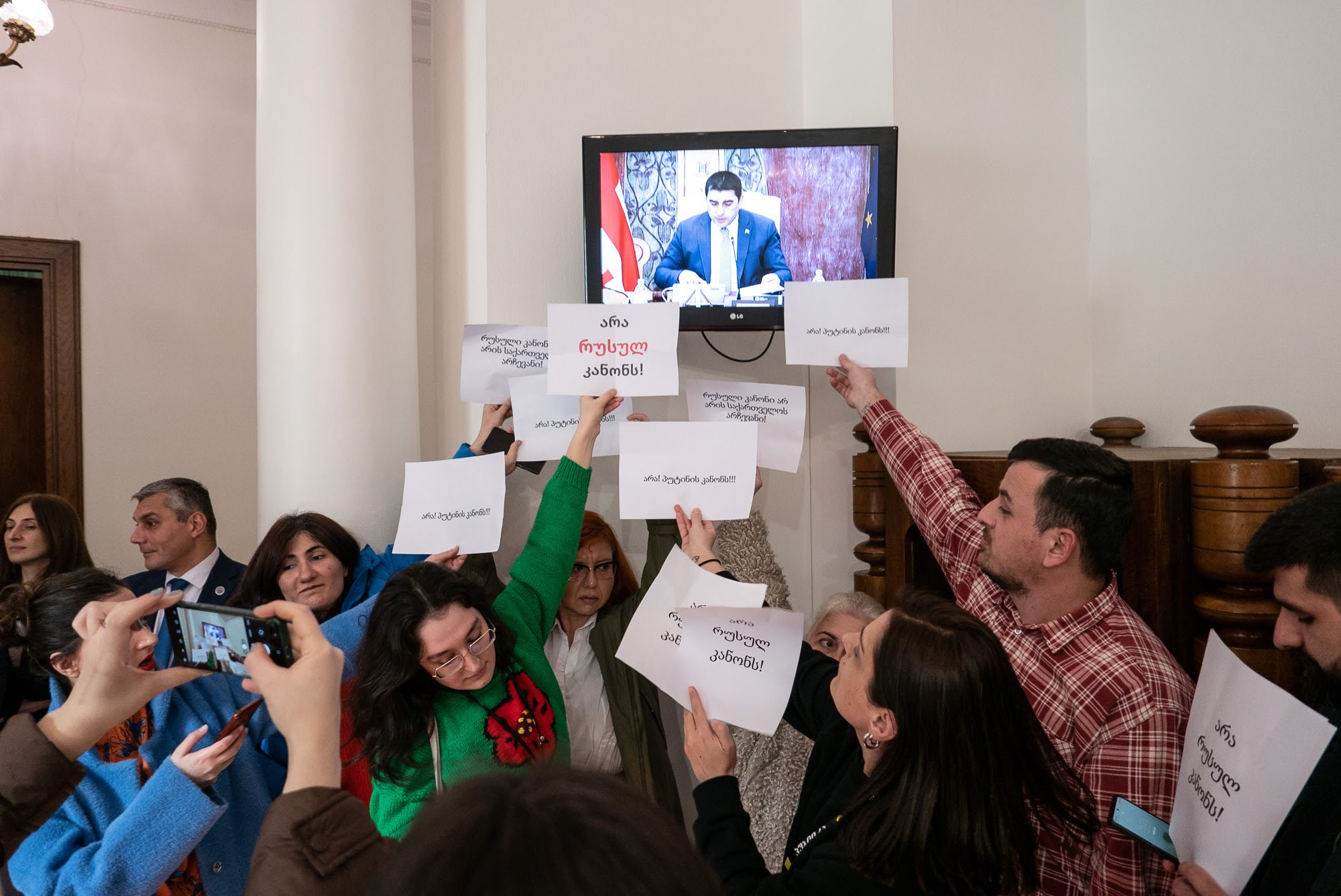

In recent years, Georgia’s ruling party have increasingly denied interviews to opposition-leaning TV stations, limited reporters’ parliamentary access citing security concerns, and suspended the accreditations of various parliamentary reporters as per amended parliamentary rules that have garnered wide local and international condemnations.

[Read more: New accreditation rules threaten to ban media outlets from parliament]

Georgia’s Constitutional Court has yet to hear the cases lodged by two Georgian TV journalists after being suspended by the parliament in May 2023 for ‘harassing’ an MP with questions.

Clearly political, not private

The political nature of the litigation is evident in both those raising the cases, and their targets.

37 out of 40 defamation cases that GDI defined as SLAPPs since 2021 targeted three opposition-aligned media groups — Mtavari Arkhi, Pirveli, and Formula — or journalists working for the companies.

Those launching the cases reliably have close ties to the government.

According to local watchdog group Transparency International — Georgia, as many as 11 municipal mayors from the ruling Georgian Dream party mounted 11 separate lawsuits against Mtavari Arkhi and its then director, Nika Gvaramia, in 2022.

Within months after the 2021 local elections, each claimed moral damage and compensation from the media group for alleging in the runup to the elections that Georgia’s security services had recruited and managed each mayoral candidate. Mtavari Arkhi defended the claims, citing anonymous sources.

To make the political message even clearer, each claimant demanded ₾55,555 ($20,000) in compensation. ‘5’ is the established election number for the United National Movement, the largest opposition group in Georgia since Georgian Dream ousted them from power in 2012.

Further evidence for the institutional nature of the cases came from a lawsuit filed by Genri Ghvinjilia, an Interior Ministry official, against TV channel Formula over a report alleging that he was involved in managing sex workers. As GDI noted, Ghvinjilia, in the capacity of a private individual, had ministry lawyers at his disposal in court.

Critics also point to the speed at which the trials have passed through typically overloaded courts. For instance, GDI notes that a case mounted by Ivanishvili’s cousin Ucha Mamatsashvili in 2022 against the Anti-Corruption Centre, after they alleged his involvement in a transnational fraud scheme and electricity price gouging, went through all three instances of Georgian court within eight and a half months; smooth access to justice that ordinary claimants lack.

According to the European Commission for the Efficiency of Justice (CEPEJ), in 2020, the civil court in Georgia took an average of 297 days to rule on a case, the appeals court — 211 days, and the Supreme Court — 433, a substantial deterioration from the 2010 figures of 108, 54, and 94, respectively.

A judiciary under government control

Georgia’s legislation stipulates a claimant has to prove that the information disseminated by a defendant was slanderous. However, GYLA’s Mariam Gabroshvili notes that the court has often taken the opposite approach, demanding that the accused defend their claims.

For example, Tbilisi Mayor Kakha Kaladze launched a lawsuit regarding claims that buses had been purchased by the city at an inflated price, and the suggestion that this was connected to Kaladze. While the lawsuit against both a media outlet and a journalist are active, neither the mayor nor the City Hall have issued a statement regarding how much was paid for the buses.

‘This sort of practice by the Georgian court contradicts Georgia’s legislation and the European Court of Human Rights approach’, says Gabroshvili.

The Georgian courts have also frequently allowed claimants to sue media groups together with journalists, despite Georgian legislation clearly stating that the owner of a media outlet should be the defendant in defamation cases relating to the work of a journalist at that media outlet.

Georgia’s Law on Freedom of Speech and Expression also stipulates that ‘value judgements’ are ‘protected by an absolute privilege’. The same law also grants a qualified privilege to a false statement if it was made ‘to protect the legitimate interests of society’ and if its benefits ‘exceeded the damage caused’.

This high bar for protecting free speech did not stop Tbilisi City Court in April 2022 from imposing a ₾100 ($37) fine on government critic Shota Dighmelashvili for making an accusation he could not prove.

Tbilisi City Court fined Dighmelashvili, a co-founder of the anti-government Shame movement, for supposedly slandering Nino Tsilosani, a lawmaker from the ruling Georgian Dream party and, recently, the parliamentary vice-speaker.

The activist insists that, speaking at a protest in mid-2019, he repeated claims made by Squander Detector, his anti-corruption project, earlier that year: that a company belonging to a former business partner of Tsilosani, Levan Chanturidze, won a government tender to build a shelter for homeless people only because of his connections to Tsilosani.

In 2018, Georgia’s Audit Service reported that the shelter should have cost ₾2.3 million ($850,000) instead of ₾4.3 million ($1.6 million), and that among other major violations, the tender conditions were tailored to ensure that Chanturidze’s company won. The corruption watchdog added to the Audit Service’s statements that Chanturidze had connections to Tsilosani.

‘When [Squander Detector] made it into the news, nobody had a problem with it, even if we spread the information widely and media also reported about it’, Dighmelashvili tells OC Media.

But in spite of the allegations being significantly substantiated, including by a state institution, neither Chanturidze nor Kutaisi Municipality appear to have been probed. Instead, Dighmelashvili was fined, suggesting that Audit Office reports are informative but ultimately irrelevant, and corruption investigations by Georgia’s State Security Service and Special Investigative Service — highly selective at best.

‘This was entirely a logical conclusion and the only person punished in this entire story related to stealing ₾2 million turned out to be me. Therefore, I think this is a case of SLAPP’, says Dighmelashvili.

His case is currently pending at the Supreme Court.

‘The point is to make anyone think twice before speaking out’

Dighmelashvili says the case did not substantially affect his life, but adds that that was not the aim of the litigation.

‘This was a sort of show trial, to send a serious message to everyone: “Are you sure you want to have a problem?” ’, says Dighmelashvili. ‘The main point is to make everyone think twice before speaking out against something. The target audience is much wider than the specific individual being sued.’

While the claimant may intend to distract a defendant rather than win the case in court elsewhere, in Georgia, an unreformed judiciary widely believed to be suffering from a lack of political independence appears to ensure a victory for a more powerful party.

In their 2023 country report, the European Commission noted that ‘recent libel and defamation lawsuits and verdicts [in Georgia] have a problematic effect on critical media reporting’.

Such comments echo the EU’s wider criticism of diminishing political freedoms and a lack of institutional reforms in Georgia, including uninvestigated cases of ‘intimidation and physical and verbal attacks on media professionals’ and senior government officials using ‘strong language against media’.

[Read more: US sanctions senior Georgian judges for ‘undermining rule of law’]

As Georgia’s government doubles down on building an increasingly stifling media environment in the run-up to the 2024 general elections, as well as establishing new forms of pressure on civil society organisations and independent media, it looks likely that such cases will only increase.

As GDI states, the trend aims to silence critical media and journalists, and so threatens free media and free speech.