Mining is one of the most important sectors of the Armenian economy; it has the largest share of exports constituting more than half the total value. On 9 March 2017, Armenia became a candidate country for the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). Candidacy means the country must undertake a series of reforms within a set timeframe to comply with standards of transparency and accountability.

Mining is one of the most important sectors of the Armenian economy; it has the largest share of exports constituting more than half the total value. On 9 March 2017, Armenia became a candidate country for the Extractive Industries Transparency Initiative (EITI). Candidacy means the country must undertake a series of reforms within a set timeframe to comply with standards of transparency and accountability.

The situation

Armenia is rich in a number of metal ores: iron, copper, molybdenum, lead, zinc, gold, silver, aluminium, and rare metals which naturally occur in the aforementioned ores. Copper and molybdenum are the most significant for the country. The largest mine in the country, the Kajaran copper and molybdenum mine, claims reserves of 2.24 billion tonnes of ore — 6 percent of global molybdenum reserves. Kajaran also accounts for 60% of mining turnover in the country. Given its confirmed reserves and the current rate of mining (18 million tonnes per year), the mine could be operational for another 100–120 years.

According to data from the Ministry of Energy Infrastructure and Natural Resources, there are 670 solid mineral mines, 30 out of which are metal mines. On 1 January of 2017, there were 431 mining companies licensed in the country, 28 of which are for metals. Copper, gold, and molybdenum have the largest share of Armenian metal exports. Eighteen of the 28 licensed mines contain polymetals and gold, 9 contain copper and molybdenum, and 1 contains iron.

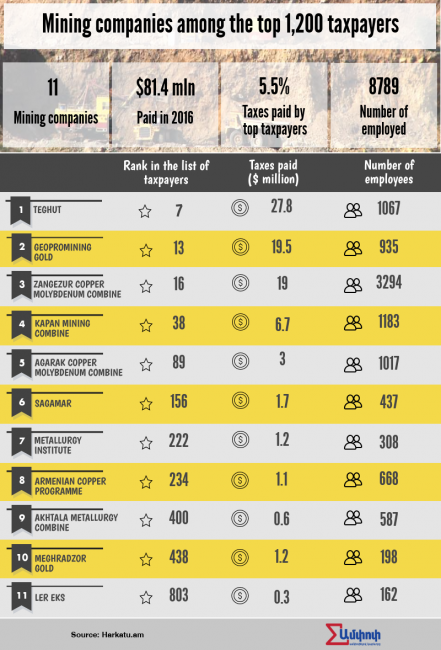

The mining sector employs around 10,000 people. The nominal monthly salary in the industry is ֏345,000 ($710), which is double the national average salary (the high salary is because of the high value of the product, profitability of the sector, and work-related life and health hazards).

According to the official data, in 2015, 16.4% of the entire industrial output of the country was in mining (֏221 billion, $456 million); next year, the number was 16.7% (֏239 billion, $494 million). Mining accounted for 4.4% of GDP in 2015; in 2016, this number fell to 2.6%.

However, the share of the industry in exports remains over 50%, with copper alone taking up 23–26% all exports.

As a result, mining and associated industries are an important source of government revenue; companies operating in the sector are large taxpayers. In 2016, 11 of the 1,200 largest tax-paying companies were related to mining, and the taxes paid by these companies (including customs, duties as well as other dues to the state budget) totalled around ֏39.1 billion ($81.4 million).

Lack of transparency

Despite the sector’s economic importance, transparency of information regarding the owners of the mines is problematic, as there are simply no publicly available names of shareholders of the companies. The companies’ official websites also do not contain any ownership details. There is hope, however, that EITI membership could bring greater transparency.

The second largest copper mine after Kajaran is the Teghut mine in northern Armenia’s Lori Province, which belongs to the Vallex Group. The mine became operational in late 2014. According to the company’s website, the mine contains 454 million tonnes of ore with concentrations of 0.36% of copper and 0.02% molybdenum. The processing plant is expected to have a capacity of 7 million tonnes per year.

Gold mining is primarily from the Sotk mine (Gegharkunik). Gold is also a major product of Dundee Precious Metals’ Shahumyan mine. Lydian International’s Amulsar mine also contains gold ores which are low in concentration but vast in volume. The latter obtained its license in 2012, and construction is planned to be completed by the Spring of 2018. The first gold bar is expected to be molded in March 2018.

According to Lydian International’s website, the mine contains reserves (meaning concentrations at least 0.2 grammes per tonne) of 67 million tonnes. The actual average concentration of metals in the ore in this mine is, however 0.79 grammes per tonne for gold and 3.68 grammes per tonne for silver. They say they intend to operate the mine for 10 years, producing 5,700 kilogrammes of gold per year. Yearly revenue, calculated from current market prices, will average around $200 million per year.

The background

Mining in Armenia goes back centuries. Copper mining in Alaverdi (Lori Province) started in 1770 and in Kapan in 1840. The Kajaran mine was opened in the mid 20th century.

During Soviet years, the mines and factories of Kapan, Alaverdi and Agarak, Zod (Sotk), and Ararat were the giants of the Armenian mining industry. Armenia played a significant role in the the USSR’s mining sector, and was the 3rd largest mining republic after Russia and Kazakhstan.

After the collapse, mining companies which were previously state-owned were gradually privatised, lasting up until the mid-2000s, after which the state no longer had any share in mining.

It is the story of the privatisation of the largest company, the Zangezur copper-molybdenum factory in 2004, that is the most noteworthy. From this company, 60% of shares were obtained by German company Chronimed, 15% by Armenian company Makur Yerkat, while Armenian Molybdenum Production and Zangezur Mining took 12.5% each. The face value of the shares totalled only $132 million.

The argument

In every country, expansion of the mining industry is usually criticised by a considerable share of society. The main issue is that non-sustainable development of the sector comes with environmental risks and environmental damage to surrounding areas.

The reference shelf

This is the reason environmental movements protest against unsustainable use of natural resources, and sometimes even demand a stop to mining altogether. There have been active environmental movements in Armenia since the mid-2000s, and these gained new momentum when several new mines started to operate. ‘Save Teghut’ was one of the most active civic initiatives in Armenia. Its aim was to prevent the operation of mines in Teghut by Vallex. Vallex obtained a license for the mine in 2007, but it became operational only in 2014. The delay was partly caused by these active civic initiatives.

The result of these active civic movements is that mining companies now see a civic hand over them, and are careful to avoid it. It’s no coincidence that EITI membership will involve active participation from civil society in monitoring and auditing the mining industry.

This article is a partner post written by Hakob Safaryan and edited by Suren Deheryan, with infographics by Nare Hovhannisyan and Astghik Gevorgyan. The original version first appeared on Ampop, on 8 May 2017.