Members of Salam, an activist group of ethnic Azerbaijanis in Georgia, are collecting signatures to have the Russian endings stripped off of their surnames.

Salam members have a month left to collect at least 25,000 signatures for the lawmakers to consider their draft law.

The initiative envisages amending Articles 64 and 65 of Georgian Law on Civil Status Acts to let Georgian citizens ‘whose surnames end with inauthentic/non-traditional suffixes’ have those endings removed entirely or have them replaced with ‘traditional/authentic’ suffixes that ‘already exist’.

The campaign was started by ethnic Azerbaijanis in Georgia whose family names, typically ending with -ov, -ova, -ev and -eva, would be allowed to have the suffixes, which are Russian in origin, removed or have them replaced with typical Azerbaijani endings.

If the draft law is supported, Beniamin Kasimov, one of the ethnic Azerbaijani campaigners, would be able to change his legal surname to Kasim Oghlu, as would Aitaj Khalilli, a 24-year-old originally from Gardabani Municipality whose legal name now is Khallilova.

Campaigners hope that the collection of signatures with typical Azerbaijani suffixes — including -oghli/-oghlu and -qizi — would also serve as evidence for the civil registry authorities that such ‘original’ forms of surnames already legally exist.

Salam, a grassroots organisation, advocates for equal rights for, and stronger public engagement by, ethnic Azerbaijanis in Georgian public life and has been behind several recent campaigns and protests, including opposing early marriages and promoting greater access to basic goods for rural Azerbaijani communities in Georgia.

[Read more on lived experiences of ethnic Azerbaijani Georgians on OC Media: Voice | ‘They say Georgia is a tolerant and diverse country; these are just words’]

‘Don’t waste your time’

The Georgian Law on Civil Status Acts formally allows a person to change their surname to one which was used by someone from their familial line up to four generations ago. The law also permits recovering one’s ‘historical’ surname provided that ‘evidence’ supports the claim.

According to Merab Kartvelishvili, Human Rights Program Director at Georgian Young Lawyers’ Association (GYLA), civil registry archives are not a very helpful instrument for ethnic Azerbaijanis, in this case, as surnames with Russian-style suffixes have been in place for generations, some dating back to the pre-Soviet period.

Salam members have also reported, and OC Media has independently verified, a practice of civil registry authorities informally advising applicants against trying to change their surnames.

‘I was told I had to pay ₾300 [around $100 in late 2019] when I first applied to change my surname and they also told me it would probably be rejected’, Sema Sadiq, 21-year-old board member of Salam who wants to change her current legal surname from Sadikovi, told OC Media.

Petitioners, supported by GYLA, Social Justice Center and several other major Tbilisi-based rights groups, also cited, among others foreign cases, the 2016 decision by Lithuania’s authorities to allow their citizens to have suffixes of their surnames changed or removed.

Separate bill?

Mikheil Sarjveladze, Chair of the Parliamentary Committee on Human Rights and Civil Integration, told OC Media on 17 August that he had not seen Salam’s draft but that they are working on a separate bill to address this matter anyway.

Sarjveladze said the discussion will have a broad format and will involve different ethnic minority communities in Georgia.

Sarjveladze has said that he will abstain from commenting on the bill extensively until September but noted that amendments addressing surname endings should be ‘accurate and clear’ before they are passed into law.

Meanwhile, this summer, some opposition leaders, including right-libertarian leaders Zurab Girchi Japaridze, Iago Khvichia, and Vakhtang Megrelishvili, have publicly endorsed Salam’s demands.

According to Salam, former European Georgia member and the country’s first ethnic Georgian Muslim MP Tariel Nakaidze is among their supporters, and many others are expected to join.

Not only for ethnic Azerbaijanis

Salam members travel nationwide almost daily not to miss any large settlement populated by ethnic Azerbaijanis in Georgia. They say they want their signature lists to be long enough for the parliament to field the draft law for discussion but also to be diverse and regionally representative.

The campaign, according to Kamran Mammadli, an ethnic Azerbaijani community organiser who seeks to have his legal name changed from Mamedovi — goes beyond ethnic Azerbaijanis of Georgia.

‘In the case of Yazidis in Georgia, it’s often -ian or -ov’ suffix forms… One lady came to our office recently saying her mother was Greek with the -ovi ending and that she wanted to sign the petition’.

Sulkhan, a 30-year-old ethnic Kist and an activist from Georgia’s Pankisi Valley, said he also tried to have his family name changed from Georgainised Bordzikashvili to an original Kist version, Bordzgēr, but that it was impossible to provide the authorities with the requested archival documents.

‘I absolutely support [Salam’s campaign]’, Sulkhan told OC Media. ‘There is a hope that I’ll be able to change my surname with their help’.

‘Occupation’

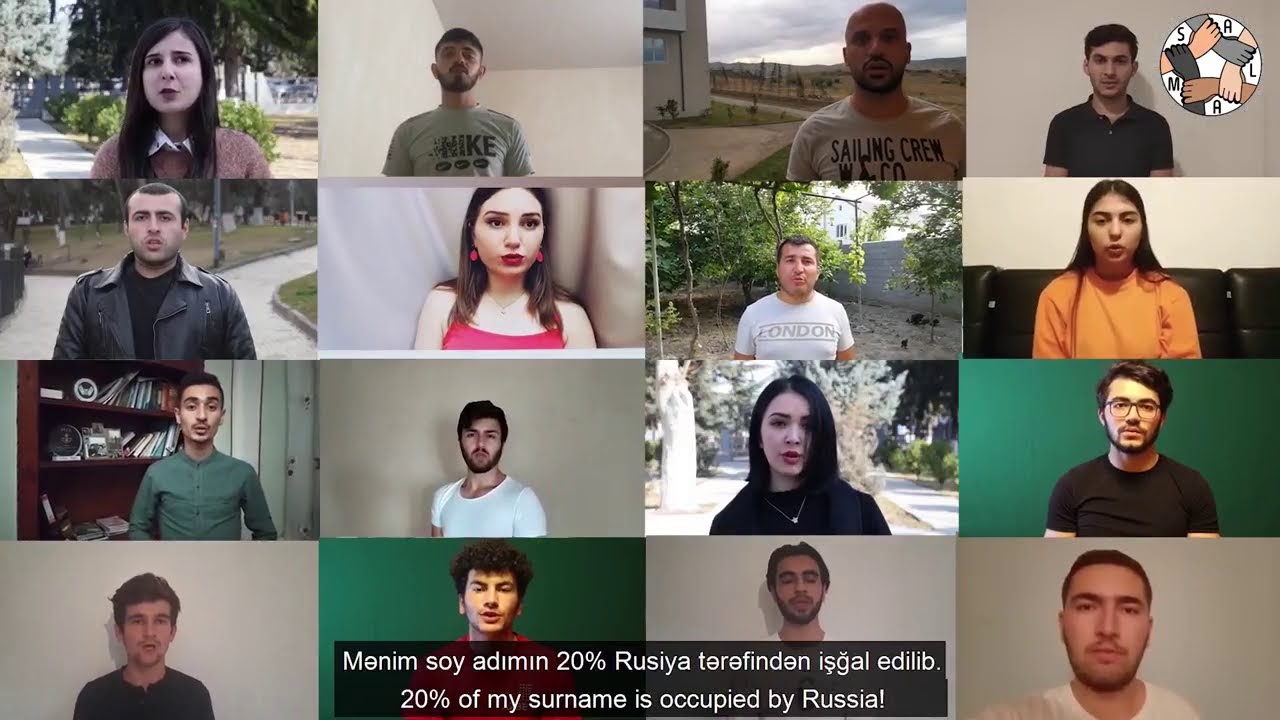

In a country where most Georgians decry Russia ‘occupying 20%’ of Georgia, referring to Abkhazia and South Ossetia, Salam has promoted the idea that surnames of many Georgian citizens have been equally ‘occupied’ and need to be ‘liberated’ from the heritage of Russia’s domination and assimilationist policies.

Activists point out that ethnic Azerbaijanis were given surnames with Russian suffixes since the 1840s under the Russian Empire and especially during the Soviet Union, and that other ethnic groups have had similar historical experiences.

‘While some are afraid of Europe, what we have to show actually is that Europe respects our identity, our authenticity’, 24-year-old Rabil Ismail, legally Ismailov, one of the five authors who lodged the draft name-change law in the Parliament, told OC Media on 16 August.

‘I think that our surnames are indeed occupied by Russians’, ethnic Azerbaijani journalist in Georgia Jeikhun Muhamedali told OC Media. ‘We are not obliged to have surnames with Russian endings’.

Thirty-three-year-old Muhamedali, who was raised in the southern Georgian city of Marneuli, said his legal name is Narzalovi but that he doesn’t use it publicly and has, so far, been unable to change it.

Samira Bayramova, an ethnic Azerbaijani civil activist in Georgia, ‘welcomes’ Salam’s initiative but also has some misgivings about its effects.

‘I don’t want all this leading to me being labelled as a “guest” and connected with the identity of another country as I’ve been fighting this all my life […] I don’t want [to have my surname end in] -zade, for instance’, Bayramova told OC Media on 13 August.

What Bayramova referred to was a trend in Azerbaijan to ‘de-Russify’ Azerbaijani surnames, often by replacing a suffix with a Russian origin to the -zade suffix which is common among Iran’s ethnic Azerbaijanis. She also referred to a common discriminatory discourse in Georgia that describes ethnic Azerbaijanis as ‘recent guests’ in the country.

Both Samira Bayramova and Salam decried the Georgian Parliament earlier this year for referring to the community of ethnic Azerbaijani citizens of Georgia as a ‘diaspora’.

Salam member Rabil Ismail told OC Media that the last thing they were interested in was endorsing a surname suffix that someone would associate ‘with another empire’ or with neighbouring Azerbaijan.

Ismail, who is from the village Darbazi of Bolnisi Municipality, also noted that as some ethnic Azerbaijanis treat it as part of genuine ethnic Azerbaijani identity, they leave the matter up to individuals while the campaign is about anyone’s right to restore the family name in a way one sees appropriate.

Samira Bayramova, meanwhile, underlined that it is a responsibility of the state, first and foremost, to invest in its own citizens’ quest for identity and to help all ethnic groups on this journey.