On 5 July, a homophobic riot broke out on the streets of Tbilisi, leading to injuries and possibly a death. While Georgia’s population is generally conservative, what do people think of the events of 5 July, and how have these views shifted since a similar riot on 17 May 2013?

On the morning of 5 July 2021, hundreds of Georgians responded to the calls of the Patriarchate of Georgia and far-right, pro-Russian, and anti-Western groups to protest against the planned Tbilisi Pride march.

Ostensibly planned as a peaceful prayer in the front of the Kashueti Saint George Church, located on Tbilisi’s Rustaveli Avenue, violence soon broke out. Protestors, overwhelmingly male, ransacked the offices of Tbilisi Pride, the organisers of Pride Week, and of the Shame Movement, an activist group.

The protestors turned rioters dispersed a camp of anti-government protestors in front of the country’s parliament building. The mob assaulted more than fifty journalists, one of whom passed away a week later.

The events of 5 July were reminiscent of those of 17 May 2013, when a similarly violent mob, also supported by the Georgian Orthodox Church and various far-right groups, attacked a handful of queer rights activists on Rustaveli Avenue who were marking International Day Against Homophobia, Biphobia, and Transphobia. The police’s inaction in both situations seemingly further emboldened the mobs.

But what do Georgians think about the events of 5 July? Data from CRRC Georgia’s omnibus survey shows that while most Georgians think that holding a pride march posed a danger to the country, the majority is against the violence that took place and supports the freedom of speech and expression enshrined in the country’s constitution.

Importantly, compared to 2013, the majority of Tbilisi residents do not approve of physical violence — even against those who, in their view, threaten national values.

Awareness of the 5 July events

Eighty-five percent of Georgians have heard about the 5 July events in Tbilisi. Those that had heard about the rallies found out on TV (69%) or social media (45%). One in ten heard about the riots from acquaintances who were not there, while one in fifty claimed to have heard directly from witnesses to what happened.

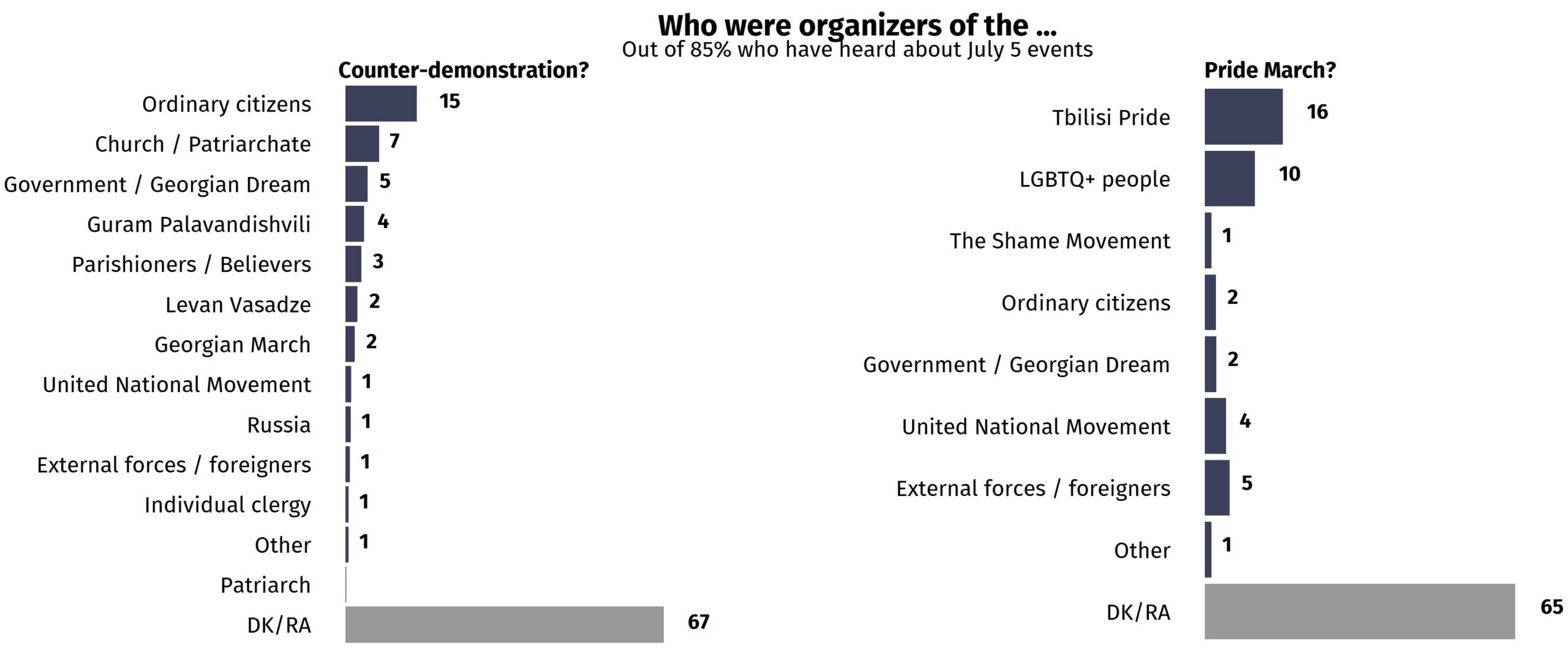

The majority of Georgians who had heard about the 5 July events were unsure who the organisers of either the Pride March (65%) or the counterdemonstration (67%) were.

Sixteen percent said that the Tbilisi Pride civic organisation organised the Pride March, while 11% named LGBTQ+ people. Some (5%) mentioned outside forces or foreigners, while 4% named the opposition United National Movement.

As for the violent counterdemonstration, 15% of those who had heard of the 5 July events said that ordinary citizens were behind it. In total, 8% reported that radical groups and leaders organised the counterdemonstration, including the Georgian March, Guram Palavandishvili, and Levan Vasadze.

Seven percent named the Georgian Orthodox Church while 5% believe that the government and the ruling Georgian Dream party organised the counterdemonstration.

Would holding a march have endangered Georgia, in the public’s view?

Many politicians, including the prime minister of Georgia, Irakli Gharibashvili, refrained from supporting the Pride March. Gharibashvili even alleged that through organising the Pride March, ‘radical opposition groups’ were stirring up ‘civic unrest’ and ‘chaos’ in the country.

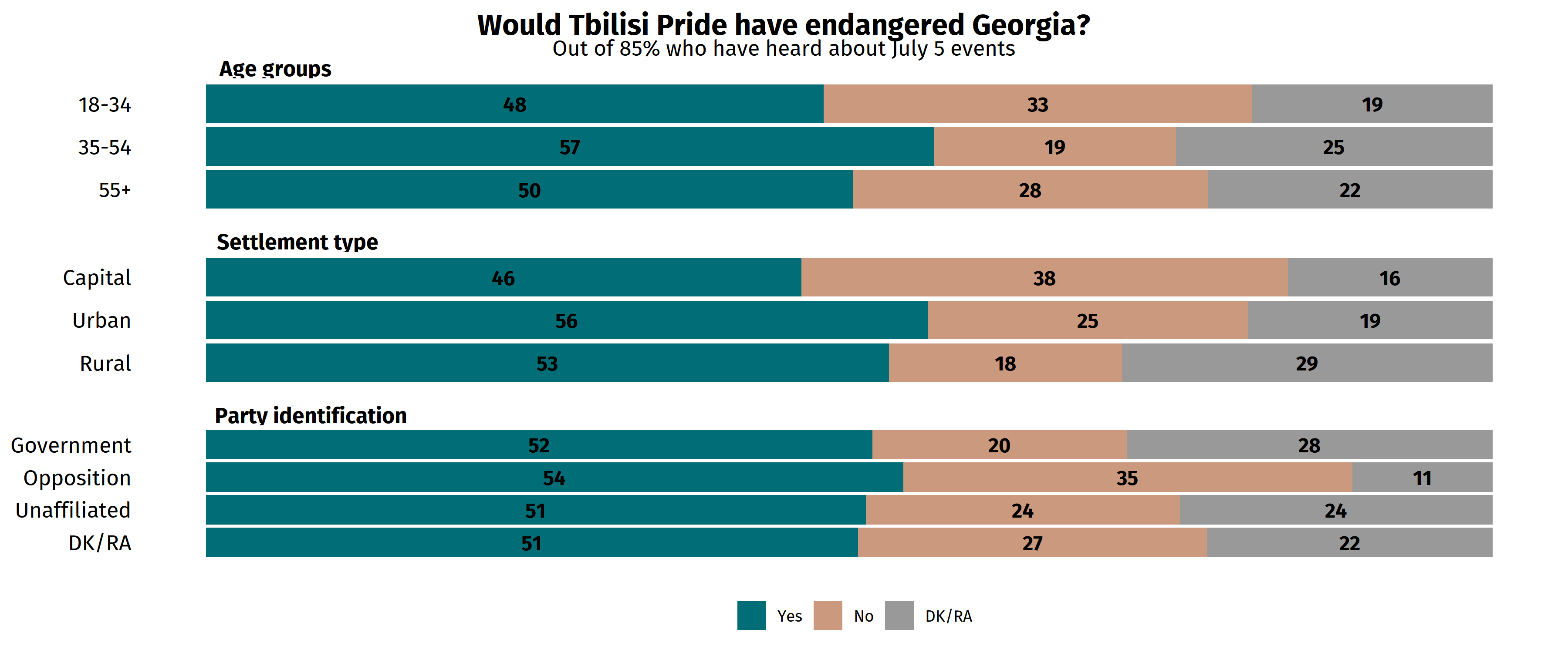

While half of Georgians (52%) who had heard of the 5 July events said the Pride March could have endangered Georgia, more than a quarter (26%) thought it would not have created problems. Additionally, 22% were unsure.

There was relative consensus on this across major social and demographic groups. Still, fewer young people (48%) believed the Pride March posed a danger than people aged 35–54 (57%). Similarly, young people were less uncertain and more likely to think the march would not have been a threat.

Tbilisi residents too were less likely to agree that Tbilisi Pride would have harmed Georgia (46%) than people in other settlements, and were more likely to believe that the Pride March was not a threat.

While a similar proportion of people from across the partisan spectrum perceived danger in the Pride March, opposition supporters were more likely to disagree with this perception.

While most (54%) still agreed that organising a pride march would have endangered the country, 35% disagreed. Supporters of the government, and those who were unaffiliated or refrained from reporting their political sympathies, were more likely to be uncertain in their views than opposition supporters.

What did the public think of the violence?

While with the church’s blessing, far-right groups violently retaliated against activists and media workers on 5 July, few in Georgia approved of such conduct.

Ninety-one percent of Georgians who had heard about the 5 July events said that physical violence is unacceptable in any circumstance.

Sixty-nine percent disagreed with the proposition that violence was admissible against a group that jeopardised national values.

Three-quarters of Georgians (74%) fully or partially agreed that the country’s constitution should grant freedom of expression to anybody, regardless of their racial, ethnic, religious, or sexual identity.

How do Georgians evaluate the response of different actors?

Opinions are split when it comes to the assessment of how different actors responded to the 5 July events, with a significant proportion of the country’s population having ambiguous views.

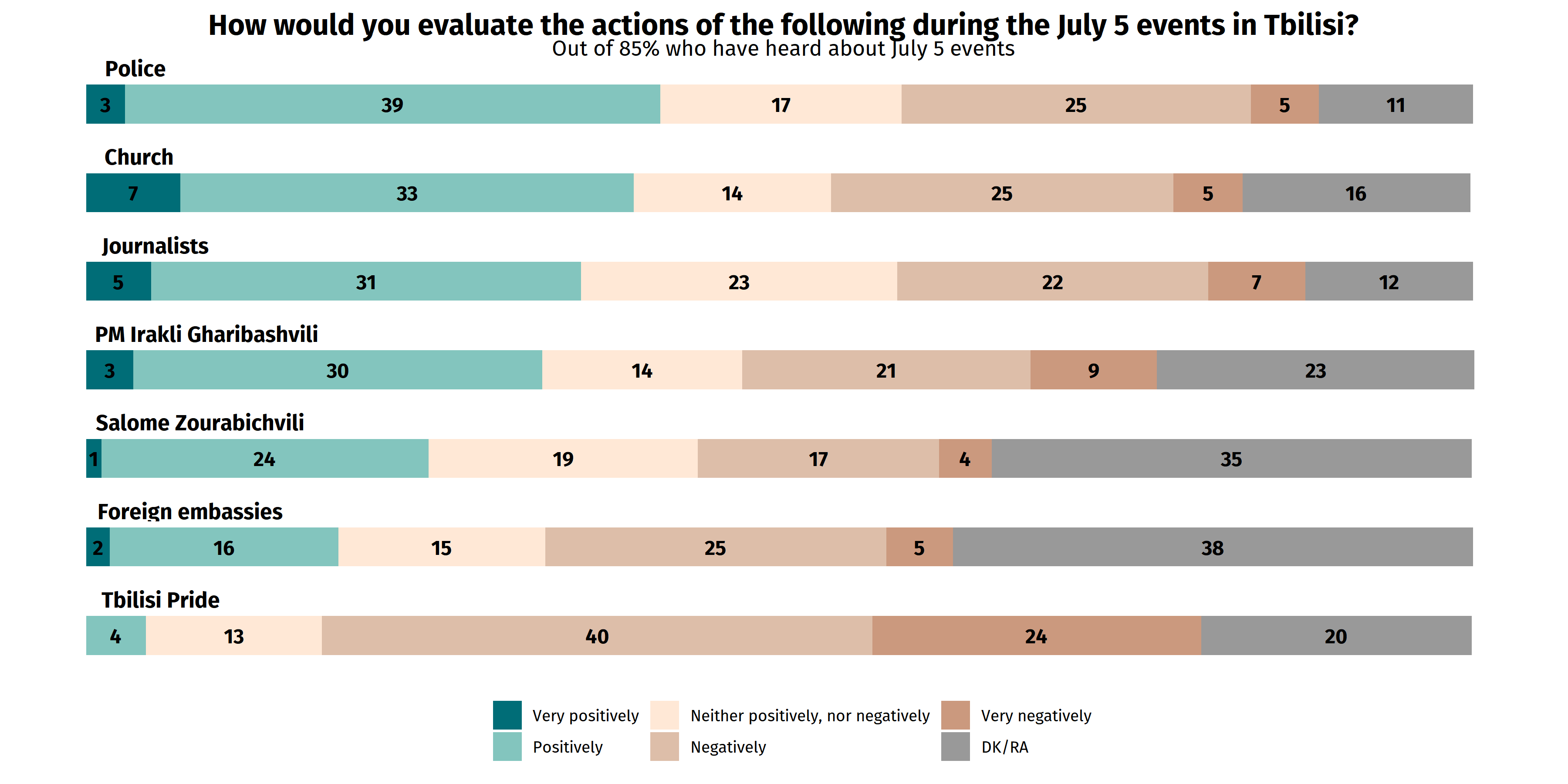

Forty-two percent positively evaluated the police’s work, while 30% negatively assessed how law enforcement agencies handled the situation.

Forty percent had a positive outlook on the church’s actions, with 30% negatively evaluating the Georgian Orthodox Church’s handling of the 5 July events.

More Georgians (36%) had positive views of journalists’ work than negative (29%).

Roughly similar shares of Georgians had positive (33%) and negative (30%) views of the prime minister’s actions during the events.

The plurality of Georgians were ambivalent when assessing the work of president Salome Zourabishvili and foreign embassies. More Georgians think positively about Zourabishvili’s handling of the situation (25%) than negatively (21%), yet more people either viewed her response as neither positive nor negative or were uncertain about it.

About thirty percent negatively evaluated the work of foreign embassies, as opposed to 17% who saw their actions during the 5 July events in Tbilisi positively, though again, people were mainly ambivalent or uncertain. The majority (64%) negatively assessed how the Tbilisi Pride organisation handled the situation.

How have attitudes changed in Tbilisi since the 2013 riots?

A set of similar questions were asked to Tbilisi residents in late May 2013 about the 17 May 2013 homophobic riot.

In 2013, about 57% of Tbilisi residents believed that an anti-homophobia rally would have endangered Georgia, while 30% disagreed.

After eight years, while the plurality of Tbilisians still believes in the dangers of the Pride March, more agree that such events do not threaten Georgia.

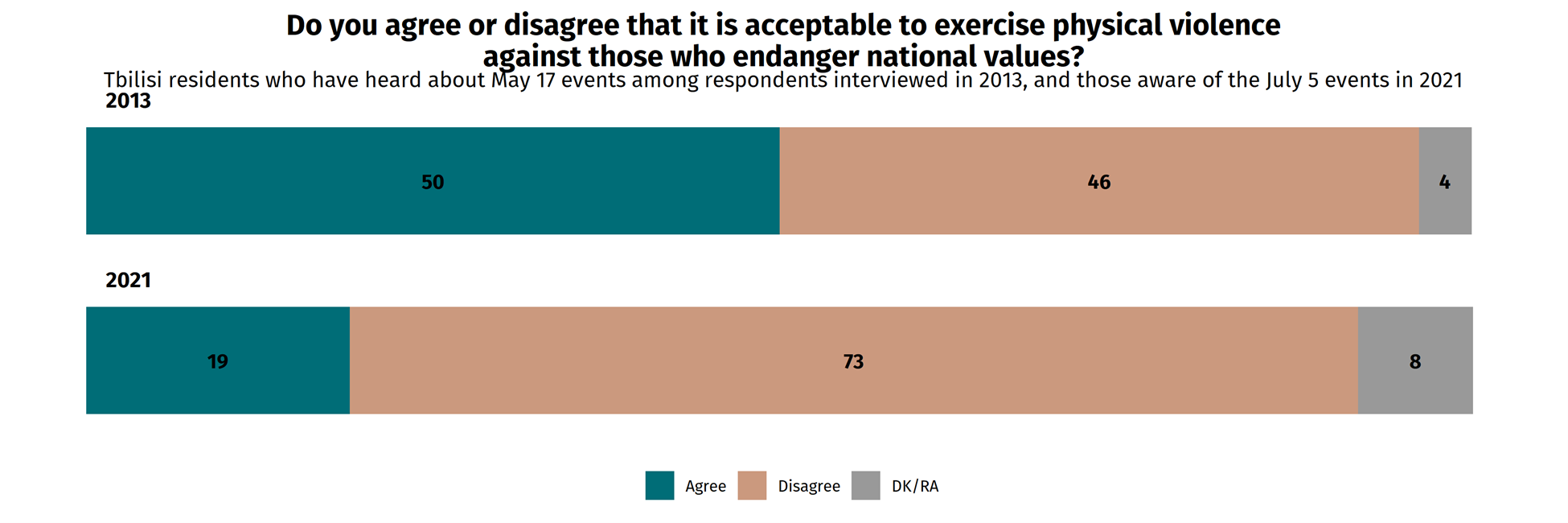

Compared to 2013, the opinions of Tbilisi residents on whether physical violence is acceptable against those endangering national values have shifted significantly.

In 2013, half of Tbilisians said they approved of violence in such circumstances, while 46% disapproved.

According to the omnibus data, eight years later, almost three-quarters of people living in the country’s capital disagree that physical violence is acceptable against those endangering Georgia’s national values.

The 5 July events shocked Georgia. While the country’s population is socially conservative and religious, the majority does not approve of violence, even against those who, in their view, might present a threat to national values.

Importantly, survey results also suggest that compared to 2013, Georgians’ attitudes have shifted. While a plurality of Tbilisi’s residents still believe that LGBTQ-themed events pose a threat, the proportion of those who think so has decreased by almost ten percentage points.

Seemingly, Georgians slowly but steadily have come to the view that violence is unacceptable, contrary to what some church leaders and politicians might have called for.

Note: This analysis makes use of a multinomial regression model predicting Georgians’ attitudes on whether holding a Pride March have endangered Georgia or not. Covariates include standard sociodemographic characteristics such as gender, age, settlement type, education, ethnic identity, partisanship, and a durable goods index.

The views presented in the article do not represent the views of CRRC Georgia or any related entity.