When the wording of questions in post-election polling is modified, the responses from survey respondents change along partisan lines.

Self-reported election turnout in post-election surveys is often considerably higher than official turnout records. The gap likely stems from picking too many active voters as respondents since voters are also more likely to participate in surveys. Yet another potentially more substantial reason is over-reporting due to social desirability bias: respondents feel they are under social pressure to demonstrate fulfilment of their civic duties on election day.

This blog describes a replication of a widespread approach to reducing social desirability bias in self-reported turnout by asking the turnout question in three different ways: a traditional direct question, providing an example of turnout over-reporting, and including face-saving answer options in the turnout question.

The question wording did not have an effect on self-reported election turnout overall, because different partisan groups reacted to the question-wording in different ways. Non-partisans and opposition supporters were less likely to report turnout when additional information was provided. In contrast, telling Georgian Dream supporters about turnout over-reporting increased over-reporting among Georgian Dream supporters.

Many studies have demonstrated that wording matters for turnout questions: when respondents are exposed to a straightforward ‘yes’ and ‘no’ question about their participation in recent elections, they tend to over-report. However, when respondents are also given an option to select face-saving responses in addition to ‘yes’ and ‘no’, self-reported turnout decreases.

A large-scale study of 19 surveys in five democracies, which used the face-saving response option, ‘I usually vote, but did not this time’, showed mixed results. In 11 surveys, face-saving options significantly decreased self-reported voting, while it had no effect in the remaining eight cases.

According to official data, 57% voted in Georgia’s parliamentary elections in 2020, while 75% said they did on the Caucasus Barometer survey right after the elections. To investigate whether people report their voting differently depending on the question wording, an experiment was conducted on CRRC-Georgia’s omnibus survey (12-19 April, 2021).

The sample was randomly split into three equal groups. One group received a traditional direct question about whether they voted or not in the October 2020 parliamentary elections. The second group received information about the discrepancy between official statistics and survey results (57% official, 75% reported) before asking about their own turnout. The third group could select two additional options in addition to ‘yes’ and ‘no’: ‘I intended to vote, but could not manage at the last moment’ or ‘I did not intend to vote, but was asked at the last moment and did not refuse’.

At first glance, the data appear to suggest voters over-report turnout no matter the question formulation. On the traditional direct question, 77% reported voting. When the over-reporting message was included, the number declined to 73%, though the difference is not statistically significant. The question with additional face-saving options also resulted in a substantively similar number (79%).

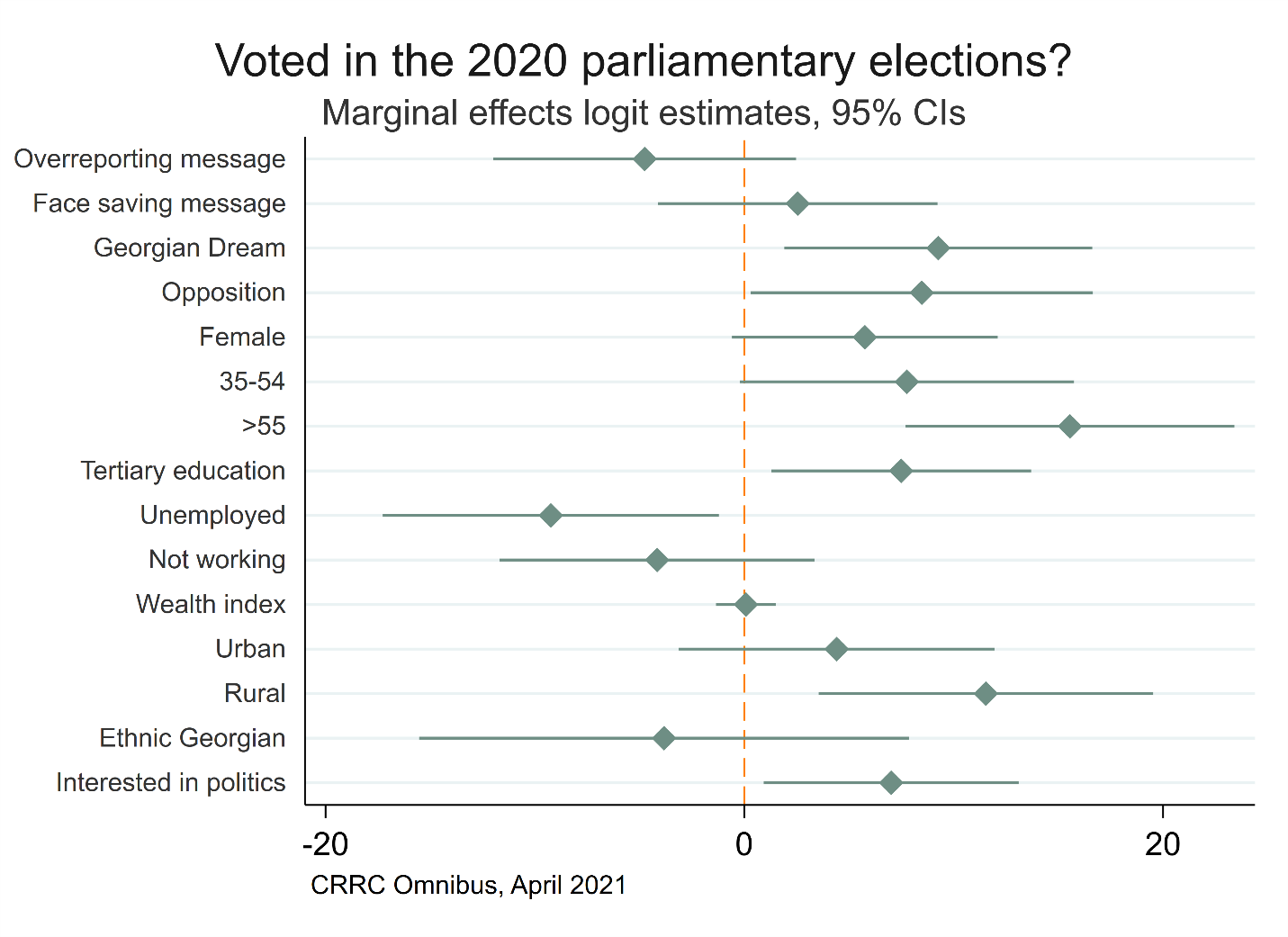

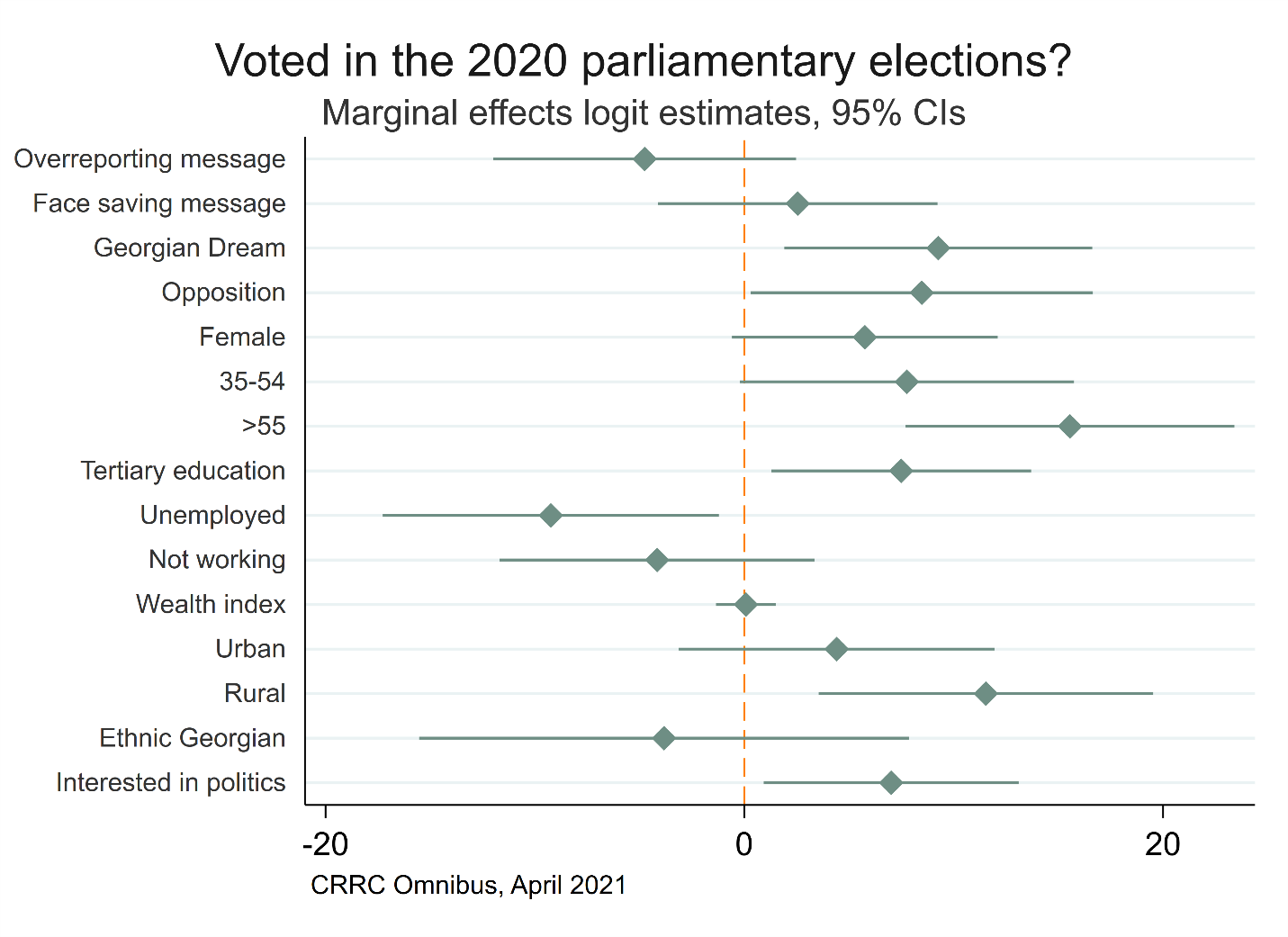

Looking at who was more or less likely to report voting, partisans were significantly more likely to report voting than non-partisans (i.e. those who could not name any party closest to their views or were not sure if such a party existed). Likewise, residents of rural areas were more likely to report turnout than voters in Tbilisi. Voters with tertiary education, voters above the age of 55, and employed people reported voting more often than voters with no tertiary education, younger voters, and those not working.

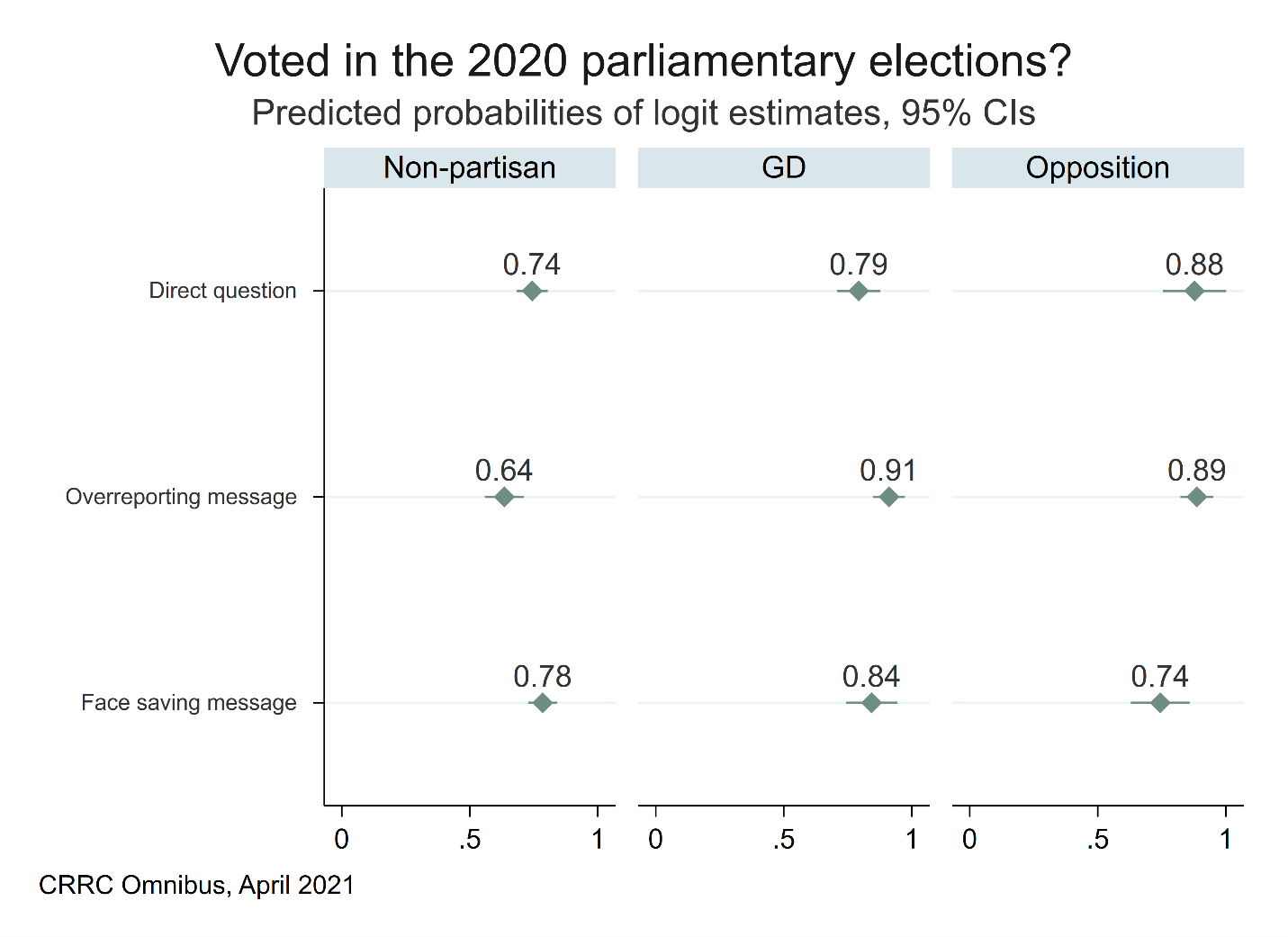

While the three types of questions made no difference for the population at large, they had significantly different effects on supporters of different parties. For non-partisan voters, the over-reporting message worked as intended, decreasing reported turnout from 74% to 64%. On the other hand, face-saving options did not change answers of non-partisans significantly. For Georgian Dream voters, the over-reporting message had the opposite effect. When they heard that the public significantly over-reported turnout in recent elections, their reported turnout increased from 79% (on the direct question) to 91%. For opposition supporters (all parties combined except for the ruling party), face-saving options had the expected negative effect, it reduced reported turnout from 88 to 74%.

This survey experiment showed that question-wording does not have an effect on reported turnout, overall. However, the reason for the overall zero effect is that different question types have different and opposing effects for different partisan groups. While for non-partisans and opposition supporters more nuanced question wording significantly decreased self-reported turnout, for ruling party supporters, the over-reporting message served as a mobilizing factor. When exposed to the information that over-reporting was a norm, they felt that they had to over-report even more.