Prior to the most recent episode in Georgia’s political crises, COVID-19 was the country’s main concern. Yet, data on how the public views the country’s handling of the crisis shows a stark partisan divide.

It has been a year since the first case of coronavirus was detected in Georgia. Since then, over 260,000 cases have been confirmed, over 3,300 fatalities, and the economy has suffered the largest decline since 1994. In light of this, how does the Georgian public assess the country’s handling of the pandemic?

Data from the 2020 Caucasus Barometer survey offers a snapshot of how well people think the country did in dealing with the outbreak.

The data suggests that there are few differences between demographic groups, but that political division is evident in evaluations of the country’s performance.

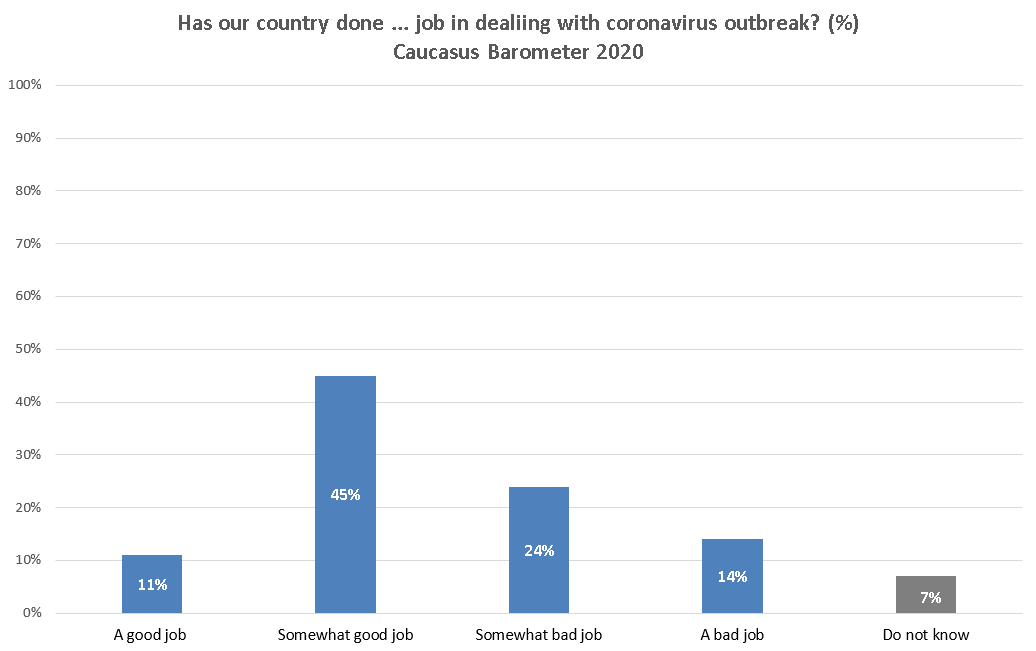

A slight majority (56%) reported that Georgia had done a somewhat good job (45%) or a good job (11%); 38% said it had done a bad job.

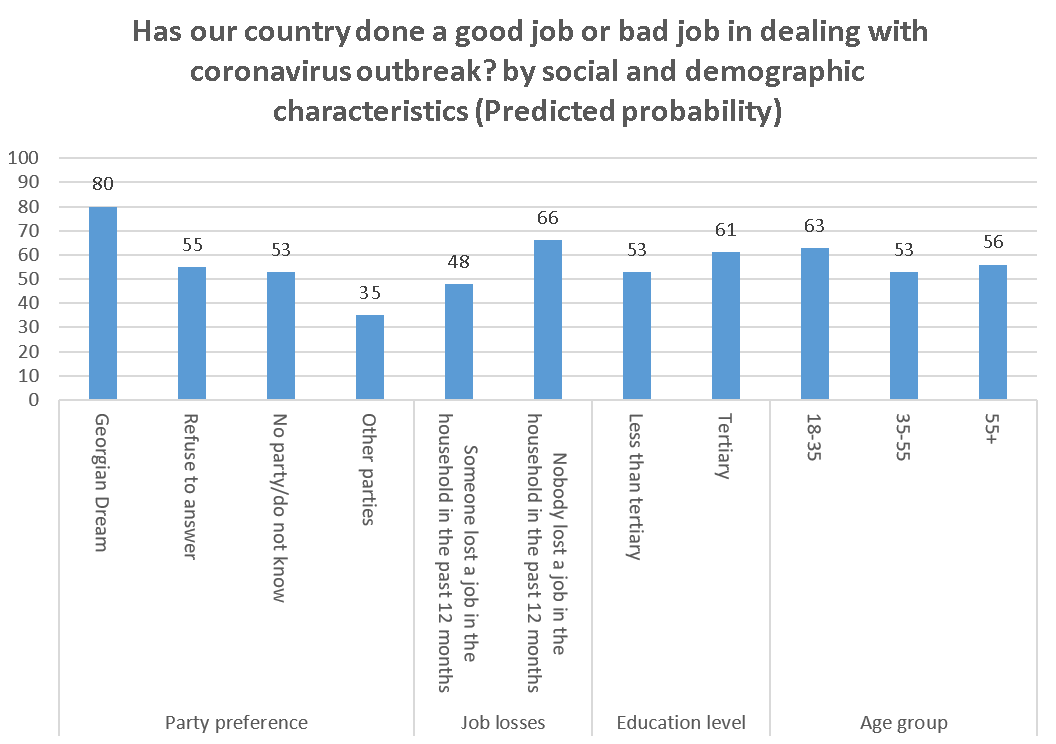

People’s assessments were associated with several social and demographic variables.

People with higher education were 8 percentage points less likely to praise the country’s response than those with a lower level of education.

People aged 35–55 were 10 percentage points less likely to report that Georgia had done well than younger people (aged 18–35).

Other socio-demographic variables, including IDP status, ethnicity, employment situation, settlement type, sex, wealth, or whether or not someone had tested positive for COVID-19, did not appear to be associated with how well someone rated the country’s performance.

While there were relatively few differences between social and demographic groups, there was a stark partisan divide.

Georgian Dream supporters were 45 percentage points more likely to report that Georgia had done a somewhat good job or a good job in dealing with the outbreak than supporters of other opposition parties, after controlling for other factors.

Similarly, Georgian Dream supporters were 27 percentage points more likely to give a positive assessment than those who supported no party in particular.

People who experienced economic hurdles in parallel with the outbreak also assessed the country’s performance differently.

Those who lost a job in 2020, or had a family/household member lose a job during the past year were significantly (18 percentage points) less likely to evaluate Georgia’s handling of the outbreak positively.

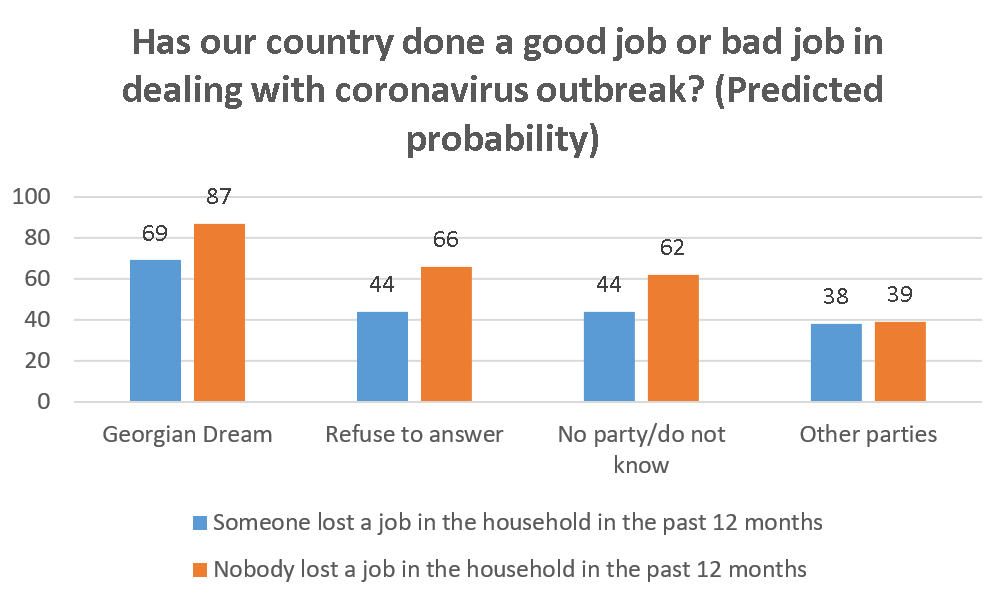

The loss of a job and partisanship also interacted in interesting ways.

Georgian Dream supporters and those with no clear political preference were significantly less likely to assess the government’s response positively if they or a family member had lost a job.

In contrast, for supporters of opposition parties, there was no significant difference between those who had or had not lost a job in the past 12 months.

All else equal, the data suggests that party identification is strongly associated with people’s assessment of the country’s handling of the outbreak.

It is impossible to determine with the data at hand if party identification drives the differing assessments of the government’s performance or vice versa.

In either case, it reaffirms what previous studies have suggested about the political polarization of the Georgian electorate being reflected through divergent assessments of past events and institutions rather than opposing policy alternatives or ideological views.

This, once again, underscores the necessity of responsible political leadership that would unite rather than divide the nation during crises.

Note: The above data analysis is based on a logistic regression model which included the following variables: age group (18–35, 35–55, 55+), sex (male or female), education (completed secondary/lower or incomplete higher education/higher), settlement type (capital, urban, rural), wealth (an additive index of ownership of 12 different items), did anyone in the household lose a job in the past 12 months, party support (Georgian Dream, refuse to answer, no party/do not know, other parties), did they test positive for COVID-19, ethnic group (ethnic Georgian or other ethnic group), employment situation (working or not), IDP status (forced to move due to conflicts since 1989 or not). The analysis was run with and without attitudinal variables, with substantively similar results. The estimates in this article present the results of the model with attitudinal variables. The data used in the article is available here.

The views expressed in this article are the author’s alone and do not represent the views of CRRC Georgia or any related entity.