Threats, corruption, nervous breakdowns, and $4,000 coats. In part two of OC Media’s exposé on Georgia’s textile industry, investigative journalist Tamuna Chkareuli goes undercover at the Geo-M-Tex factory in Tbilisi.

[In this multi-part series, OC Media went inside Georgia’s factories for a first-hand account of the working conditions. Read Part I here.]

It was easy to get a job at the Geo-M-Tex factory. The Human Resources manager did not ask many questions — just briefly explained that as a newbie, I would perform basic sewing operations and learn them step by step.

I was told to come the next day when she would meet me by the security stand and escort me to one of the four workshops — coats, trousers, cutting, coat filling — that the factory is divided into.

But no one met me on the first day. When I entered, security just told me to follow the women on the factory’s lower floor, to the place where they manufacture jeans.

My job consisted of marking the spot for buttons and then attaching them with three different presses — a hazardous job, since the press slams down in the blink of an eye.

We were working on special protective trousers from Uvex — a German sports clothing brand. The thick, denim-like material left a layer of blue dust over everything in the entire workshop. I still prefer not to think of how much of it ended up coating the insides of my lungs.

There were about 30 of us in the room, amidst a constant din of machines that drowned out everything but the angry yells exchanged between workers and supervisors.

It was stifling and impossible to breathe. The air conditioner was on, but all it could do was emit a useless, lukewarm wheeze. Even it, it seems, had succumbed to the blue dust.

Produce in Georgia

The Produce in Georgia programme was unveiled by the Georgian Government in June 2014.

It is supposed to encourage investment in the manufacturing sector by providing co-financing on loans and handing out state-owned property for the symbolic price of ₾1 ($0.35).

Through it, the government promotes Georgia as a growing market with minimal red tape, low utility prices, and very competitive labour costs.

According to the programme’s official website, the apparel production sector ‘is characterised by […an] extremely cheap workforce (around $265 per month)’.

Their brochure on manufacturing also boasts of a ‘favourable labour code’, continuing on to say that, ‘the country doesn’t have minimum wage regulations and compensation for labour depends on the agreement between employee and employer’.

In fact, there is a minimum wage in Georgia, one that has not changed since 1999. It is a mere ₾20 ($7) per month — a bitter point of contention for trade unions and labour rights activists.

Produce in Georgia has succeeded in promoting ‘nearshoring’ — a relatively new tendency in the apparel sector that allows major brands to save on shipping costs to EU markets by producing in Eastern Europe, the Caucasus, and Turkey.

There are currently 13 factories operating in Georgia that have benefited from the programme.

A textbook beneficiary

Geo-M-Tex is a textbook beneficiary of Produce in Georgia, receiving a preferential loan of ₾5.5 million ($1.9 million) and a building for ₾1 so it could open a factory and manufacture western brand-name clothing for export.

The factory was opened in 2015 and, until 2017, was majority-owned by two individuals, Lasha Bagrationi and Ramaz Sagharadze, with each controlling 42.5% of the company’s shares.

Lasha Bagrationi is the son of Mukhran Bagrationi, a powerful Tbilisi businessperson who owns three large retail zones in the centre of Tbilisi, as well as the construction firm Ekometer, which has built two upscale residential projects and the Besiki Business Centre in the Georgian capital. Lasha’s older brother, Giorgi Bagrationi, before he became the head of the Security Police department at the Ministry of Internal Affairs, was a former head of the Municipal Inspection Department at the Tbilisi City Hall, and was also previously the head of the Samgori District Municipality.

Seventy-two-year-old Ramaz Sagharadze is the father-in-law of Grigol Morchiladze, a wealthy entrepreneur and influential political figure.

In April 2014, Morchiladze was appointed by Economy Minister Dimitri Kumsishvili as an advisor to the chair of the National Agency of State Property, the very institution that allocates properties and buildings to Produce in Georgia beneficiaries, just one year before the opening of the Geo-M-Tex factory.

Morchiladze is also the former business partner of the Minister of Regional Development and Infrastructure, Zurab Alavidze, and major donor both to the opposition United National Movement party and the ruling Georgian Dream party, having donated ₾60,000 ($37,000) to the former in 2012 and ₾50,000 ($20,000) in 2016 and ₾60,000 ($22,000) in 2017 to the latter.

Following a labour and quality control scandal in 2017, Ramaz Sagharadze legally became the sole owner of Geo-M-Tex.

Despite his official ownership of the factory, workers at Geo-M-Tex still regularly referred to it as ‘Morchiladze’s factory’. Many of them believe that the Morchiladze is the real owner, with Saghardze acting as a thinly veiled middle-man.

Locked doors

We worked from 09:00–18:00 with three breaks: 10 minutes at 11:00, 40 minutes at 13:00, and 10 minutes at 16:00.

I noticed guards always appeared in break areas several minutes before the clock ran out to tell everyone the break was over. Technically it wasn’t, but as they explained, the way back to the workshop took two to three minutes.

That’s why on a 10-minute break no one could relax or even smoke a cigarette properly — even if we couldn’t see them, we could always feel the security there, right over our shoulders.

The factory’s main door is locked for most of the day and was only open during the 40-minute lunch break. On short breaks, we couldn’t leave the factory and were only permitted to smoke in a little area in the inner courtyard.

For lunch, we went to the kitchen. But the fact that it was a kitchen, was, at least for us, nothing but decoration — we weren’t allowed to cook there.

All the women came with their own food and ate from plastic containers.

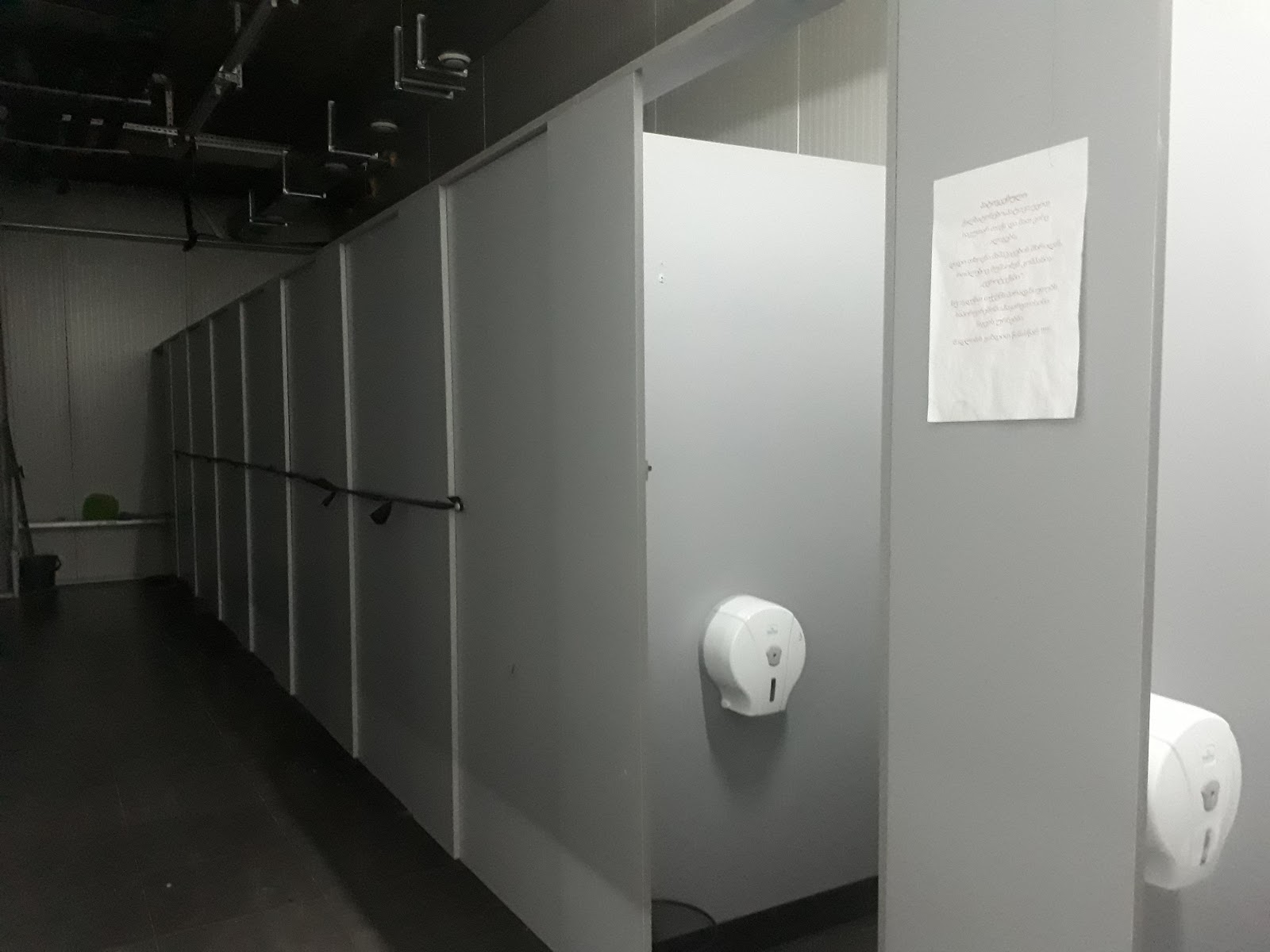

In the bathroom, two-thirds of the stalls were nailed shut and in the rest there was no toilet paper; we all had to bring our own.

Marina Blakunova

Five months after Geo-M-Tex was established, a newly-formed company, Eurotex Ltd, managed by Marina Blakunova, took over management of the enterprise.

Marina Blakunova is a stateless person born in Latvia and is a representative of the Egeria group. Her daughter, Veronika, also joined the managing team and later established her own clothing line, Movi, currently produced in Eurotex.

The Egeria group, officially registered as Egeria Limited, is a limited liability company based in Cyprus. It works as an intermediary between the factory and brands, supplying the factory with fabrics and specifications for different models.

While managing the factory, Eurotex had secured deals with the clothing brands Equiline, Dainese, Uvex, and Moncler.

Moncler was the most high-end of the brands, with winter coats retailing from $252 to $4,587. By the summer of 2019, all Moncler clothing made in Georgia was produced under Blakunova’s watch. While production processes were outsourced to different factories in the towns of Kutaisi and Rustavi, Geo-M-Tex in Tbilisi was the main production and dispatch centre.

‘Mind your fingers’

My first day was marked by two major events.

In the morning, a woman in my work area started screaming. Then she collapsed and started convulsing, it was an epileptic seizure.

After they carted the woman away, all the workers on the floor started to talk about how stressful the job was and how no one was safe from things like this.

A little while later, Marina Blakunova, the factory director, came down and began yelling at everyone demanding that ‘whoever is responsible for this’ step forward. She told us that tailors treat each other like animals and it was clearly their responsibility, not hers.

After haranguing us, Marina left and was replaced by her daughter Veronika. A little while later, a representative of a company from Italy — we suspected Moncler but could not find out for certain — joined Veronika and the two were in the workshop with us for the rest of the day.

The Italian did not seem to care that there was no air in the room, and mostly just chatted with Veronika. But, if any of the women working on the floor spoke too loud, or worse yet, laughed, then Veronika would yell at them — telling them that she was ashamed of them, right in front of the Italian visitor.

In the second half of the day, we found out that a large number of trousers had been sent back from Germany. A flawed batch. The trousers had been produced by Eurotex’s subcontractor in Tkibuli, but the final quality was checked here by both senior controllers and Marina herself. Nevertheless, she was outraged. She told us off, and said that if we made mistakes ‘we would pay for them’.

My coworkers’ faces dropped when they found out they would have to stay until 20:00, two extra hours, to fix the flawed stock. They ended up staying even longer.

The whole day, the human resources manager came to check on me only once, and even then our ‘conversation’, if you could call it that, lasted several seconds. She walked past me, and before I could say or ask her anything, she quipped ‘mind your fingers’ and then left.

I asked my supervisor if I would earn money for my first day and she said this was ‘a decision that the accountant will make’. I later found out I would be getting paid an ‘apprentice rate’, which they told me, ‘would obviously be less than that of the others’, without ever specifying a number.

At the end of the day, on my way out of the factory, the security staff checked my bag, lest I might have stolen anything. Not that theft was uncommon, in fact for one employee of the factory, it would appear to have been par for the course.

Madona’s story

Madona Tarkhnishvili began working as the assistant storage manager but was promoted to manager after her predecessor was fired for allegedly stealing several sacks of feathers.

She didn’t want the job.

‘I felt unsafe in that place because it’s the storage staff who see what really goes on in this factory.’

Indeed, Madona witnessed with her own eyes that factory director Marina Blakunova often didn’t play fair.

‘Every Moncler jacket has a sewn-in electronic chip that makes it unique’, she said. ‘But sometimes, storage would receive more material than there were chips. The material would be sent to the cutting workshop as usual, and for instance, instead of enough details for 100 coats, they would end up with the details for 120.’

‘The trick is, you can make a perfectly good Moncler coat from those. Those “Moncler” jackets, without the original chip, Marina would gift to her immediate circle or workers from the administration. Some people have seen those jackets for sale at the Lilo market [in Tbilisi] as well.’

Blakunova had a contract with an enterprise in Rustavi. Eurotex would send them the material and finished jackets would be sent back. Madona always sent the right number of goods for every order, so Rustavi manager Nugzar Kakhidze usually didn’t count what came in.

‘He trusted me. We had a good working relationship and Marina noticed it. Once, when we received expensive fur, she came to storage and before I could say anything, took a couple of pieces from the box, without tearing the security [anti-tamper] tape.’

‘This man trusts you, he won’t check’, Madona recalled Marina telling her.

Madona couldn’t sleep that night. She ended up calling Nugzar. Next day, he counted everything on the spot and when there were pieces missing, he confronted Blakunova. She, in turn, blamed Madona and said it was her mistake.

‘Since then’, Madona said, ‘she was always trying to arrange something [bad] for me’.

Meanwhile, Madona kept noticing ever more suspicious activity, as salaried positions seemed to be filled with phantom staff, or remained curiously empty.

‘My salary back then [as assistant manager] was ₾450 ($160), but no one came to claim it’, she told me. ‘[Head of human resources] Nino Eloshvili’s daughter had some position too. And so had an accountant’s mother, but no one ever saw them in the factory’.

At one point, Marina fired the cleaners and asked the regular staff to clean after themselves. Madona couldn’t help but wonder where the money went.

‘Marina doesn’t want honest workers. No one who started wondering about the money has remained in the factory for long.’

As a manager, Madona had a fixed ₾700 ($300) salary but not even once received it in full. Marina used every occasion to dock her pay.

‘She asked me to help in the cutting workshop once, but I couldn’t work there — you need to bend over a lot and my back started to hurt. She subtracted ₾150 ($65) from my salary for something that wasn’t even my job’, Madona recalled.

‘In the last month, they put a ₾5 banknote on my table and said — this is your salary for this month. You made too many mistakes to receive more’.

Because her salary had been too low, Madona ended up taking out a loan. ‘I couldn’t admit it to my husband’, she said. ‘My family almost fell apart because of this job.’

But she told me that worse than the low pay was the abuse.

‘I couldn’t stand when she [Blakunova] would start screaming for no reason. I quit after she threw a pack of zippers into my face and called me a bitch.’

Madona stayed friends with some of the people at the factory after she quit. She later found out that the head of human resources told her co-workers she was fired for stealing, ‘just like the person who had my job before me.’

The second day

On my second day on the job, I discovered that my coworkers stayed at the factory until 21:00. A 12-hour shift. I tried to figure out if they received overtime pay, or if they were paid at all for these additional hours, but no one seemed to know — not even the women themselves.

No matter who I asked about the salaries, the answer was always along the lines of ‘we’ll see how this month goes’.

As a general rule, tailors were divided into three categories according to their abilities, and for each category, there was a minimal fixed-sum paid monthly. However, the final pay still depended on the quota, so most of the workers didn’t know what they would receive at the end of the month.

Rusiko (not her real name) is in her fifties, short-haired and tall. She’s a former teacher with a dry, sarcastic wit. We ended up sitting side-by-side, and she told me her story.

She saw a vacancy on jobs.ge with a promise of ₾600 ($200) per month, free food, and health insurance. After she got the job, she realised none of that was true. There was no food, no insurance, and the most Rusiko ever made in a month was ₾400 ($140).

Most of the workers at Geo-M-Tex have been at the factory for less than half a year. All the women told me they are trying to endure the work just long enough to find a better job — they suggested I do the same. But luckily, they said, we would have a break soon.

That’s when I found out that on 24 August, everyone would be going on a month-long ‘holiday’, whether they wanted it or not. Only people who had been working there for years would receive a salary during that month; the majority wouldn’t get a single lari.

Not counting the unexpected holiday, as a new worker, I kept trying to figure out what my salary would be. It was tough. I was not working in the position I applied for, because they had me fill in for someone who had quit. As that position was one of the least skilled, all I could gather was that I could never hope to make any more than ₾550 ($190) a month, even if I worked as fast as I could and produced more than the quota.

That was unlikely, it was not a job I had experience in. It was not dissimilar to Rusiko’s situation, or that of most of the other women I spoke with. Most who worked at Geo-M-Tex had no prior textile manufacturing experience, but from day one they were expected to rapidly manufacture expensive brand name clothing, without errors, and in very large quantities.

Speed was paramount — even though it was only my second day, the phrase I heard most often was ‘work faster’.

‘Workers always pay for their mistakes’

Each pair of trousers that were manufactured at Eurotex would mean a certain amount of money for the workers who made them — one pair usually nets each worker a few tetri.

The system works something like this: a pair of jeans pays out a certain sum to the workers, that sum is multiplied by the number of jeans manufactured and then divided by the different processes of manufacture (e.g. sewing pockets, belts, attaching zippers), and by the number of workers involved in each process — some processes pay more than others.

Tailors note what process they were involved in, and how much stock they manufactured.

The one exception seems to be the button press. Despite asking repeatedly, I could not figure out how my salary was to be calculated.

Flaws in the product also seemed to be a constant issue, but management was loath to address it. Instead of allowing us to take our time, they constantly pushed us to work harder. They set unrealistic goals for inexperienced workers.

Under these circumstances, flaws in the product were inevitable.

Those in more senior positions, like technologists, supervisors, and quality controllers, however, would usually escape blame. The buck would always stop with the workers below them.

Sometimes, when I noticed a flaw and showed it to the technologist, she would tell me it was alright, and that we shouldn’t return the item to the tailors for a fix. I produced a lot of flawed trousers that day because I was so tired I could barely sit, but my superiors turned a blind eye.

Better to let some flaws through than not meet the quota, they seemed to reason.

But occasionally, heads do roll and someone in management is fired or has to pay for mistakes made by the workers. For Blakunova and top managers, it was all the same who paid the price — so long as it wasn’t them.

‘Be careful’

On a smoke break, I befriended a new girl who worked upstairs in the jacket department. She said the situation there was as bad as in our part of the factory. It was too hot and the workers quarrelled all the time. She only started to work here because she couldn’t find a job for four months.

When I met her, all she could dream about was the [unpaid] holiday. Most of the workers dreamed about it – I would hear them saying, ‘fuck the money, just let me rest a bit’.

By late afternoon, workers barely talked to each other, as no one had the energy for it. More than once I heard the women refer to the factory as a ‘madhouse’.

Maiko, who worked next to me, said she cried every day during her first month on the job. ‘But don’t worry’, she told me. ‘You’ll get used to it’.

The women would casually tell stories of how they would get home and fall on their sofa as if they were dead. I felt the same. But I had it easy. Unlike me, most of these women have families, and after work they’d have to pull a second shift of domestic labour.

I also started to develop an allergic response to something in the air. I developed an itchy rash on my face and told the other women about it. They told me they suffered from such symptoms all the time.

The cleaner was supposed to come once a day, in the morning, to vacuum, but when I saw her she merely swept the floor. At around 15:00, I started to lose concentration and a couple of times the press caught the edge of my finger.

‘Be careful’, the other women told me.

Rusiko suggested that I pretend to need to use the bathroom just so I could get a little bit of rest. She said she did it all the time.

While we were working, she too received an injury, accidentally cutting her finger with a pair of tailor’s shears. When another worker brought a first-aid kit, it turned out it didn’t contain even a single plaster.

At the end of the day, human resources head Nino Eloshvili came down to the factory floor and said that the minibus that transported workers from Rustavi to the factory would be late and they would have to stay at the factory longer.

It felt like all of us, our bodies, our time, were under nearly complete and often arbitrary control. And yet, I would later learn a story, that would make what I had seen with my own eyes almost quaint by comparison.

Lela’s story

Lela Migeneishvili, 36, the supervisor of the cutting workshop back in 2016, was the ‘director’s sunshine’ — as she told me Marina used to call her. That is, until the Sunday when her staff didn’t come in for work.

The large quantity of labour her team had to do each day put enormous pressure on the workers, and Lela would take the work home or call her team and beg them to work late hours or on Sundays. The workers weren’t paid for the overtime. Lela told me they only did it to avoid abuse from management.

Nevertheless, Lela was devoted to her job and, until that Sunday, Marina was always good to her. But this weekend was Giorgoba, a Georgian holiday in honour of Saint George. Lela did not dare to ask her staff to come to work.

The next day, the production manager of the cutting workshop reported her actions to Blakunova.

Outraged, Marina came in and began to berate Lela in front of her staff.

‘She was screaming and banging a ruler on my desk’, Lela recalled, adding that she initially hoped it would be a one-day misunderstanding, but that it didn’t pan out. ‘I was always eager to earn her approval, but she didn’t appreciate it’.

Then a new, and very complicated cutting pattern arrived that Lela couldn’t figure out quickly. She was afraid to approach Marina for help, for fear of further abuse.

As a result, the workshop did not meet its quota.

In despair, Lela asked for a few workers to help out in the workshop. Blakunova refused. When one of the workers in the cutting workshop suddenly quit because of stress Marina blamed Lela. She said that Lela had plotted with the worker to undermine her and the factory itself.

She threatened Lela, who remembered the director telling her: ‘You don’t know who I am. I will destroy your life and you will beg me to stop.’

Lela said that, at that moment, she felt like she would pass out. She stumbled out of Blakunova’s office and headed for the factory doctor. A few seconds after Lela had entered the doctor’s office, Blakunova flung open the door, screaming, and tried to lock herself in the room with Lela.

‘She absolutely lost her human face. I have no idea what she wanted to do to me in that room’. After a brief scuffle, Lela managed to get out of the room and ran to the cutting workshop.

Lela swept the cutting charts, pens, and pencils off her work table, and crumpled to the ground, sobbing. Frightened co-workers tried to pull her hands away from her face but her body was completely frozen.

Blakunova then had her thrown out of the building into the cold rain outside.

Lela was fired the day before her son’s birthday.

At first, because of Lela, the cutting shop staff didn’t receive their salaries that month. Though, after some loud complaints, the salaries were eventually paid out, except for Lela’s. After they had been paid, Lele’s co-workers collected signatures on a letter attesting that she was a bad manager and deserved to be fired.

One member of her team even wrote a letter of gratitude to the management.

Broken promises

Lela was far from the only person at the factory to suffer the wrath of Marina Blakunova and the other Eurotex managers. The same year that she was fired, 2016, almost three dozen workers, with Lela among them, approached the Georgian Trade Unions Confederation (GTUC) for aid in helping them secure unpaid wages.

The GTUC campaign was spearheaded by Giorgi Diasamidze. He told me about his first major interaction with Blakunova.

‘She told me we [Georgians] should be grateful that she gave jobs to those people’, he said. He warned Marina that the trade unions would go over her head and get in touch with the European brands, including Moncler, Eurotex’s largest partner, directly. Marina laughed it off. ‘She said that Olga Markova from Moncler is her friend, and we would achieve nothing’, Diasamidze said.

Lela recalled that representatives of Moncler would come from Italy often. Workers were forbidden from speaking to them. There was one tailor who knew Italian and talked to the Italians. She was fired.

These visitors often saw Blakunova yelling at workers, but didn’t say anything.

After the GTUC campaign, some monitoring was performed by the brand.

‘The workers were in a room with the [company] representatives for questioning, but were met by the management at the doorstep’, Giorgi Diasamidze said.

But compensation for the workers, among other demands, was only satisfied after footage of Marina Blakunova screaming at workers and preventing them from leaving the factory was posted online.

Lela received all of her unpaid wages, while other workers were only partially repaid.

That victory came at a heavy price. Lela said that several days after she got her backpay, her husband received an anonymous call claiming that Lela had sex with numerous co-workers, in the private room where she worked (in truth, she did not actually have her own room).

Lela’s husband left her and their two children.

Even though today Lela has recovered, has a new job, and lives with a new partner, she remembers her time at Geo-M-Tex as the most traumatic experience of her life.

‘For months after they threw me out, I couldn’t pass the turn-off to the factory without breaking into tears’.

The third day

The morning of my third day, Nino Eloshvili loudly announced that today those who would like to stay longer could do so. It sounded as if yesterday and the day before people also stayed of their own will. When she left the room, workers exchanged comments about how everything at the factory was ‘a bunch of lies’.

Before leaving, Nino told me she would bring some safety documents for me to sign. She never came back, but I asked other women what it was and they said they all signed this paper in which they took full responsibility for any injuries and that if they broke any of the machines, they would have to pay for them.

But these machines do not need any mistakes or mishandling to break. The dust and the regular wear and tear is more than enough. The machines seem to be just as exhausted as the workers.

That day, they also cleaned the air conditioner. They emptied a desert’s worth of dust out of it. It didn’t change much. The same with the vacuum cleaner — which, despite being emptied, just wheezed ineffectively. No matter what happens, the dust, like the management, always seems to win.

My goal for the day was to try to understand how the salaries are distributed. I spoke to the main technologist, who explained the maximum fixed salaries within three categories of workers, ₾300 ($100) — category one, ₾400 ($140) — category two, and ₾550 ($190) — category three.

But despite the apparent simplicity of the system, it is unclear how much you’ll get in the end. This depends on the performance of the workers in your section of the factory and how close you come to meeting the quota — one which is, as one technologist told me, ‘far from normal’.

She also told me that since I’m still ‘learning’ it’s hard to say what my salary will be, and I will only see how much I’ve earned on payday.

‘So what’s the point of the fixed salary?’ I asked. But, as always, I never got a straight answer. The reality is that no one knows for sure how lucky they will be next month, and no one dares ask questions.

During lunch, I meet a woman from upstairs who confirmed the unpredictable nature of payday, saying that once she missed a day because she was ill and it was subtracted from her salary.

The workers at Geo-M-Tex understand that they’re being mistreated, but they don’t see what they can do about it. Nor do they blame the government. For them, it seems, the factory is a country of its own.

‘It’s private property’, Rusiko told me. ‘They do what they want here, these are their laws.’ I remember when she said these words, she wore a scarf. Emblazed on it was the logo of Georgia’s ruling party, Georgian Dream.

After three days at the factory, I decided to talk to the HR manager and ask when I will finally be doing what I came to learn. I spent half an hour in front of the office, but she never came out. I went to the senior technologist again.

‘Oh it won’t be before long’, she told me. ‘We have a new model of trousers coming now, and there’s no one else to press buttons’.

Epilogue

After finishing my time at Geo-M-Tex, I reached out to Eurotex and the companies whose brands were made at the factory.

I asked about the litany of abuses that took place during my time there, and the terrible stories I heard.

Eurotex wrote that ‘there was never unfair or humiliating treatment in our organisation. During the three years of our operation, we never had such complaints, including legal cases’.

German clothing company Uvex, who had been manufacturing safety trousers at Geo-M-Tex, informed me that they had moved production to the factory for ‘test purposes’ and ‘finished the collaboration by the end of November 2019’.

Luxury brand Moncler wrote that they had ‘committed to respect and uphold human rights in all areas of its operations and within its sphere of influence. To this purpose, we regularly audit our suppliers through third-party inspections. This approach is applied uniformly across all countries in which Moncler operates’.

‘For your information’, they added. ‘Even if we did in the past, we are not currently working with the supplier named Eurotex.’

Equiline thanked me for informing them of what had happened at the factory but added that they ‘have always implemented the procedures and verifications according to our corporate standards without detecting anything’.

Update: When I wrote to Eurotex, Veronika Blakunova, Marina Blakunova’s daughter, supplied a document authored by Eurotex lawyers which stated that Eurotex had shut down the operations indefinitely. After completing the article, I went to check out what was happening at the factory. Part of the building was demolished, however, another part of the factory remained intact and, more importantly, seemed to be fully operational. I even saw my former co-workers walking out for a lunch break. This article has been updated to reflect this new information.

This was the second part of a multi-part investigation into Georgia’s textile industry. It was prepared with support from the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Regional Office in the South Caucasus. All opinions expressed are the author’s alone and do not necessarily reflect the views of FES.