On 12 December, Azerbaijani civilians claiming to be ‘eco-activists’ descended on the Lachin Corridor, placing Nagorno-Karabakh under de facto blockade. With their lifeline to Armenia and the world cut off, some in the region fear a looming humanitarian crisis.

‘If it continues like this, we won’t be able to last long’, says Karen Melkumyan, the director of the Arevik Medical Centre. ‘Autumn-winter is the season of acute respiratory diseases and the hospital is overloaded.’

The Arevik Centre is the only pediatric hospital in Nagorno-Karabakh. When OC Media spoke with Melkumyan on 16 December, the gas supply to Nagorno-Karabakh had been cut off for three days. The pipes bringing gas from Armenia to the region pass through land now controlled by the Azerbaijani government, a fact apparently used in the past to exert pressure.

‘We heat the wards with electricity so that the children don’t get cold. You see that the corridors of the hospital building are cold and we sit here in double clothes’, Melkumyan says.

Later that day, the gas supply was restored.

‘We’re using our medicines sparingly’, Melkumyan says, ‘so that if a child suddenly appears in critical condition, we can help them first’.

The Arevik Centre has only one ambulance, which is now stranded on the other side of the blockade after having transported a patient to Yerevan before the road was blocked.

But even if the ambulance were available, it is not clear if it would be of any use. The blockade has led to acute fuel shortages.

While the streets of Stepanakert are silent and empty, with few cars to be seen, just outside the city, where the Lachin Corridor to Armenia begins, people are waiting for the road to reopen.

‘We are from the regions of Armenia. We come to Karabakh to sell goods, vegetables, meat, fruits’, says one stranded man, huddled around a fire with several other drivers. ‘We can neither go forward nor back.’

‘We are already smelling of smoke, we have been sitting by this fire for three days day and night; we cannot bathe’, he says.

‘They say they want to open Stepanakert airport. Well, will I transport the bulls by Boeing to sell in Karabakh?’, he asks.

‘Clearly aimed at creating a humanitarian disaster’

The Azerbaijani government has denied all responsibility for both the road closure and the gas cut, blaming the Russian peacekeeping mission for the former and the Armenian authorities for the latter.

These are claims dismissed by officials in Stepanakert.

‘It’s been five days already that Azerbaijan has kept the 120,000 population of Artsakh [Nagorno-Karabakh] under total blockade with an “emotional” and attention-grabbing agenda, flavoured with fake environmental pretexts, thus putting the Armenians of Artsakh before a humanitarian disaster’, President Araik Harutyunyan said in a post on 16 December.

‘However, as we can see, the people of Artsakh do not kneel and are honourably overcoming the current processes, which are incompatible with the 21st century and almost unimaginable for a civilized people’, the President said.

Marina Simonyan, a representative of the Human Rights Defender’s Office, warns of a looming humanitarian catastrophe if the road is not reopened.

She said the region’s population, including 30,000 children, 20,000 elderly people and 9,000 people with disabilities ‘are simply deprived of any humanitarian access’.

‘Azerbaijan’s closure of the Lachin Corridor seriously violates the norms of international humanitarian law and is clearly aimed at creating a humanitarian disaster in Karabakh’, Simonyan tells OC Media

Simonyan says that around 1,100 people, including 270 children, are currently stranded, unable to return home.

‘Four-hundred tonnes of essential goods are imported from the Republic of Armenia to Karabakh daily, including grain, flour, vegetables, fruit, economic goods’, she continues. ‘Currently, the supply of these goods to Karabakh has been completely stopped.’

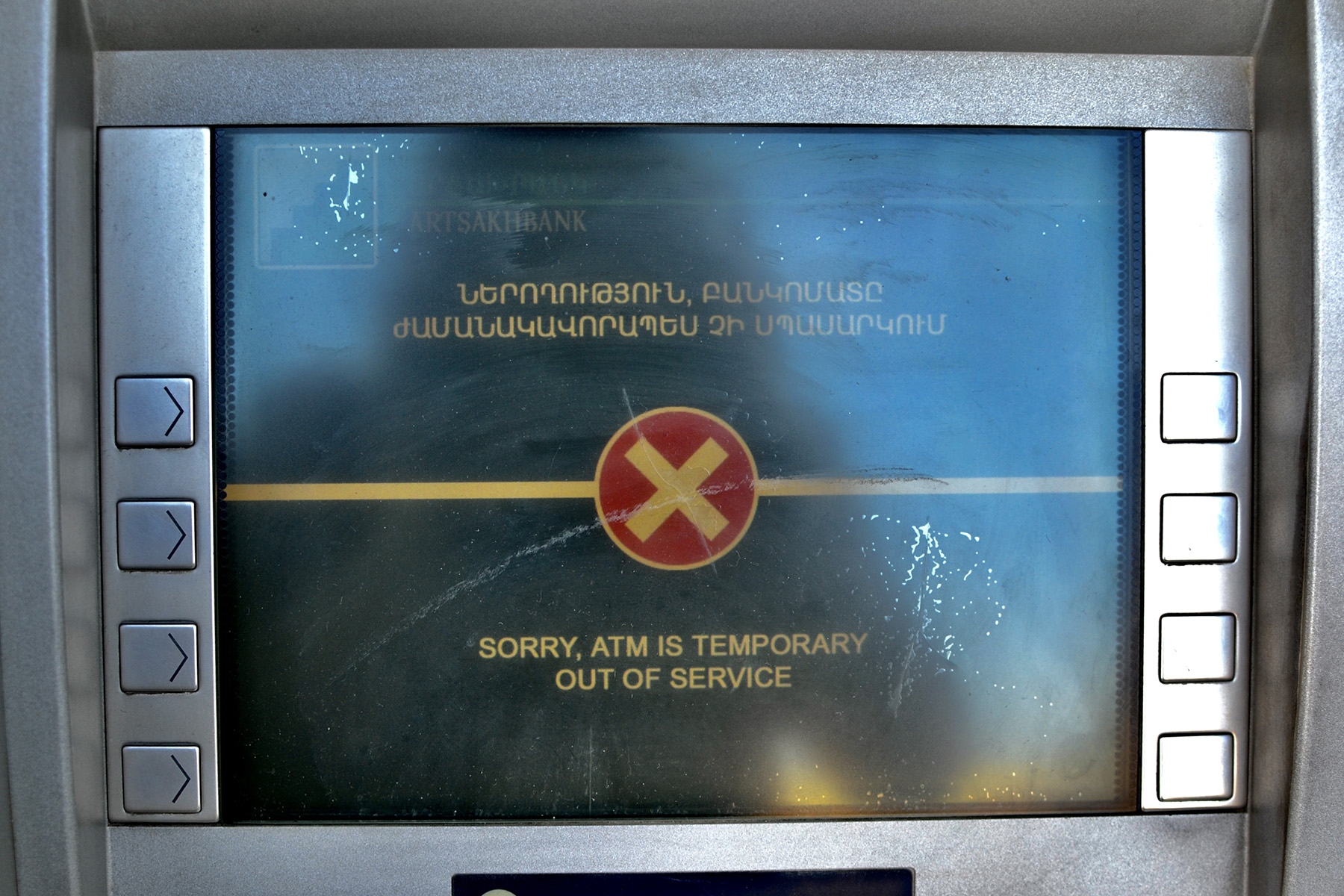

By 18 December, shortages of essential goods and medicines were already being reported.

Simonyan warns that the blockade had already created a ‘serious medical crisis’.

‘Transportation of critically ill patients who need urgent treatment and hospitalisation has become impossible, as a result of which the lives of these patients are in danger.’

‘Let them cut our electricity’

Despite the hardship inside the blockade, an air of defiance persists.

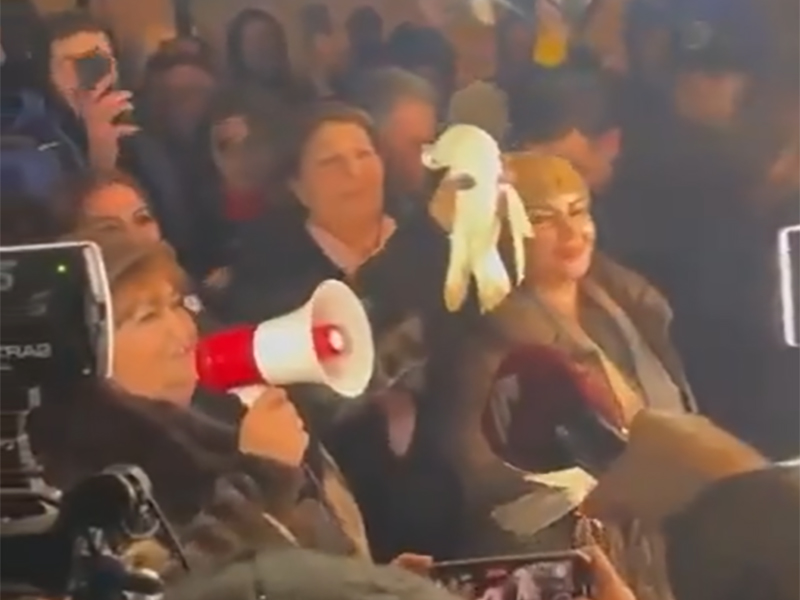

‘Let them cut off the gas for a couple of days, the electricity for a couple of days, it’s OK, we will burn wood to get warm, as long as we stay in our homes’, says Ella Ghambaryan.

‘They say we should live peacefully together, but they want to suffocate us like that pigeon she strangled to death. It was a hint, many just didn’t get it. They just want to do the same with us.’

‘I will not leave here, I have nowhere to go’, Ghambaryan says, recounting the life-changing injuries her sons suffered during the First Nagorno-Karabakh War.

‘We did not leave this land during such a difficult time, even for our family’, she says. ‘Moreover, I want to return to my native village, Chayli’ Ghambaryan says.

Almira Khachatryan, a market trader in Stepanakert, strikes a similar tone.

‘They closed the road; turned off the gas — let them turn off the electricity as well, no worries, I will survive’, she says. ‘I won’t leave here. We will live by candlelight, we will enter the bed to get warm. We endure, we are a creative people.’

But the spectre of war still casts a long shadow.

‘In the 1990s, we lived closed off for years; as we endured then, we will endure now’, Khachatryan says. ‘I just don’t wish for so many young guys to die again.’

For ease of reading, we choose not to use qualifiers such as ‘de facto’, ‘unrecognised’, or ‘partially recognised’ when discussing institutions or political positions within Abkhazia, Nagorno-Karabakh, and South Ossetia. This does not imply a position on their status.