As the coronavirus pandemic ravages Georgia, schools in four major cities and Adjara have gone fully online. But a lack of internet access in the high mountains and the financial burden on teachers and families mean many children are losing out on their education.

Lado Apkhazava is a civil education teacher who was among the finalists for the 2019 Global Teacher prize. This year, Lado has found himself selling pots of violets that he grows at home to raise money for his students.

‘I don’t know how this idea came to me, but 72 students have already got internet packages thanks to it. Of course those flowers aren’t worth ₾19 ($5.70), but when people know it’s financing the education of children, they buy them.’

This is the price for a monthly, unlimited internet package, which for many Georgian students is now the only way to continue their education. When schools switched to online learning on 30 March, Lado was among many teachers who found their virtual classrooms nearly empty.

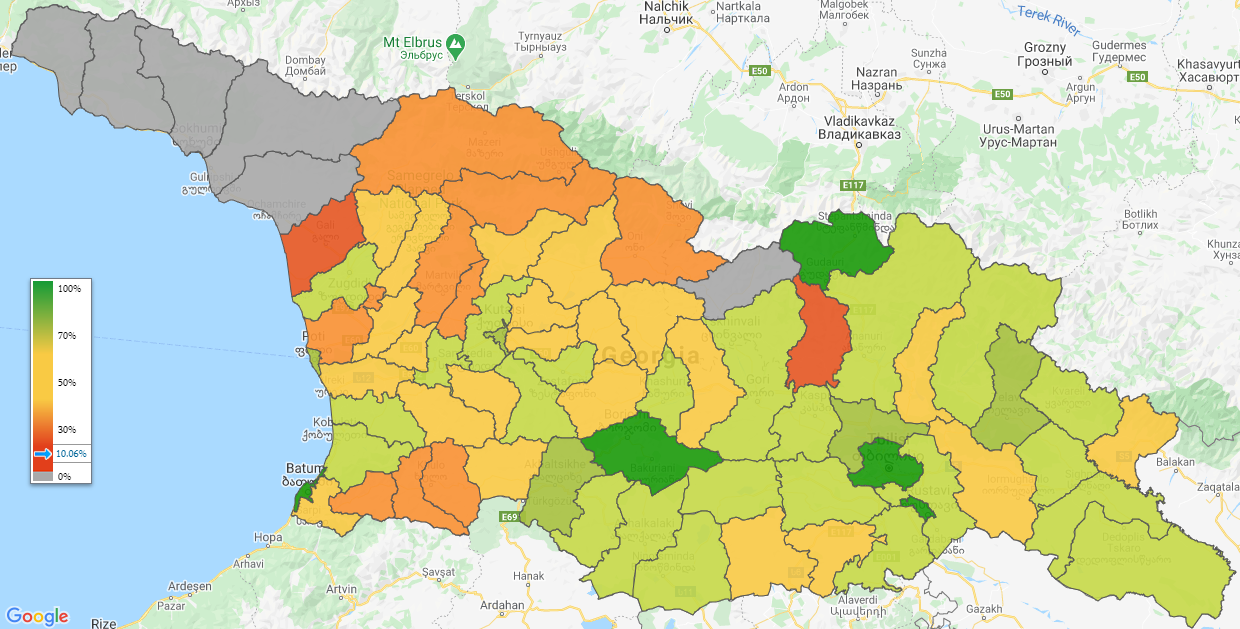

Lado lives in the village of Chibati in Georgia’s Western Guria region — a region plagued by poor internet connections. According to GeoStat, 21% of households nationwide do not have access to the internet and 38% don’t have access to a computer.

‘When I first entered an online lesson, there were two students’, Lado recalls.

He then stopped classes for a week and summoned all the resources he had at his disposal — both his own money and help from the Black Sea University, the Caucasus University and other groups — to provide internet access to the students in need.

At the beginning of the pandemic, he raised money to buy internet access for 482 students for four months. To his pride, these students haven’t missed a single class.

Nineteen lari was too much for many to gather at once, and so some opted for cheaper packages which quickly ran out. Lado says that the Microsoft Teams software favoured by the education ministry uses a lot of data, and children do not use the internet solely for educational purposes.

‘It turns out that doing a good deed can be hard too’, says Lado. ‘Many children from other regions began to call me asking to switch on the internet for them too, but I simply don’t have the ability to check on their situations.’

‘There are many families that think it’s provided by the government and demand I provide internet in their homes. On the other hand, some children developed empathy in this situation and asked to share part of their money with other children.’

Microsoft Teams was the programme of choice of the Ministry of Education, which has a five-year contract with Microsoft. However, the programme turned out to have two significant problems: along with its large data use, it is also a completely new technology for teachers.

Despite the Ministry of Education conducting webinars and training courses to instruct teachers on how to use Teams, many still struggle to adapt to the new programme.

‘Teams training is provided in the Teams programme itself, but most of the teachers are confused by it. They don’t know how to do presentations or download homework’, Lado says.

On the day we spoke to him, a full two months into the school year, Lado was teaching other teachers how to use the programme’s attendance journal. ‘Even when they learn the basics of the programme, teachers don’t trust that they will deliver their best to the students’, Lado says.

For some teachers even purchasing internet access for themselves can be a financial strain. Lado’s charity efforts have helped to finance four such teachers.

‘Sometimes my colleagues and I had to borrow money from each other’, he says.

The Ministry of Education told OC Media that teachers were eligible for cheaper internet packages.

‘All teachers are using corporate phone numbers, which give special offers for internet access. If a school is operating in a half-online regime, the teachers receive additional payment for the online lessons’, the spokesperson said.

Lado also tried to negotiate deals for teachers with large internet providers, but he said the companies had concluded it would be too difficult to monitor their use.

‘I feel like when the country is in need, it’s active citizens who need to take responsibility. I am doing what I have to, and many teachers can do the same. Yes, I have to sit at home, but I am also saving time and money this way, and I decided to use this for my students.’

Frozen teachers, muted students

Primary school teacher Viola Verdzadze also began teaching for the first time online this year. Viola lives in the village of Merisi, nestled in the mountains of Georgia’s Western Adjara region.

Although she is following the ministry’s recommendation to keep classes for primary school pupils under 20 minutes, she still finds it difficult to keep their attention.

‘The computer is very odd to them. When you have your first grader physically in class, you teach them school etiquette together with the lesson. Now they often struggle to keep looking at the monitor, even with the parent engaged’, she says.

The focus becomes even a greater challenge with a poor connection. There is no 4G connection in Merisi, and Viola often uses Facebook Messenger over Microsoft Teams for better communication. Still, it’s not ideal.

‘ “Teacher, you’re frozen.” — That’s what I often hear my students say.’

Viola is a mother of two herself, and both her children attend classes at the same time their mother is giving a lesson. She has to buy separate internet packages for all, or the connection worsens for all of them.

‘As a mother, I see a significant drop in the quality of education. In winter I expect it to get even worse, with the snow in this area, even the regular signal is sometimes lost. And some families don’t even have a phone — why should a child from such a family lose access to their education?’

‘The motivation to study “properly” is very low, especially when you know you can cheat. Especially for those students who still don’t realise they are studying for their future, and only want to get a grade.’

Khatia Turmanidze, 16, also lives in Merisi. Even though she now has three to four classes per day, instead of six, attendance in Khatia’s class has halved. In a few cases, classes have been suspended simply because no students joined.

‘It’s very hard for us to get used to this style of studying, it’s almost like a cultural shock. When you’re at school, you’re focussed on learning, but at home, there are distractions and household responsibilities. The other day I muted my microphone, put my phone in my pocket, and helped clean the tables.’

Poor connections decrease the motivation of the students too — they simply don’t want to enter a class for the fourth time, after the call keeps dropping, Khatia says.

Khatia and all of her classmates use mobile internet, which creates inequality.

‘I have a classmate who didn’t attend classes for two weeks because she was waiting for a sale on internet packages.’

Stalled internetisation

Talks about ‘Nationwide Internetisation’ have been going for the past six years. First mentioned by then-prime minister Bidzina Ivanishvili in 2014, in 2015 the programme was officially announced by Georgia‘s Innovation and Technology Agency. A year later, the government issued a decree announcing that a special Non-legal entity, OpenNet, would deliver a programme of ‘wideband, fibre-optical infrastructure that will result in the country being fully covered with fibreoptics’.

However, the project hasn’t taken off. In 2019, Minister of Economy Natia Turnava mentioned at a press conference that nationwide internetisation had been ‘temporarily suspended’ but that the government was ‘actively working’ on the problem. She said that was due to criticisms from the private sector, and that the Ministry was working on a model that would not compete with private business.

This year, the project was rebranded as Log In Georgia. With the help of the World Bank, $40 million was allocated to provide connections in the regions by 2025. The project’s website states that ‘Internet communication became even more important during the COVID-19 pandemic when the majority switched to the online platforms’.

Indeed, the pandemic only highlighted an ever-persistent infrastructure and financial problems. To this day, crucial access to the internet is provided by charities.

Charte is a project by Educare Georgia that has connected secondary school students to the internet since 2017. Mari Gelashvili, who manages the project, says that since the beginning of the pandemic their work has doubled.

‘We have provided connections for over 300 families this year and donations have increased, but at the moment we have queues for internet providers to install optical internet, and many people are still waiting’.

The price of internet installation ranges from ₾100–₾160 ($30–$48) from local providers, and monthly packages begin from ₾20 ($6) per month. Charte works mostly with socially vulnerable students who they find through schools and field trips.

‘However, we have received requests from many regular families too’, Gelashvili says.

No changes to the curriculum

The Young Pedagogues Union conducted a study over the first months of the pandemic that showed that teachers were not ready for the challenges to come.

‘Most of the teachers we spoke to stress that there was no timely action from the side of the ministry’, one of their researchers, Khatia Tchanishvili, tells OC Media. ‘Some schools have decided to tackle the problems independently, but the overwhelming majority waited for the ministry’s directives and were disappointed.’

Teachers coped by creating Facebook Messenger groups, but in this way, only seven students could attend the class.

The research showed that online classes caused difficulty for families with many children too, as the lessons overlapped and families often had only one computer or phone.

Khatia says that many teachers tried to work with the government’s regional educational resource centres to help organise their work routine.

‘The position of the ministry was that all students should join the learning process by any possible means. Teachers reported that even though they tried their best, they couldn’t cover the national curriculum.’

A spokesperson for the ministry told OC Media that there had been no change to the curriculum as there was no need for this.

‘The national curriculum is only a framework of goals, and it is up to teachers how they lead their students to achieve them. The schools were recommended to plan the study process with complex and diverse tasks for students, which becomes especially relevant in online education.’

‘These types of tasks envision independent work for students with constant feedback from the teacher, which can happen both during online lessons and with additional consultation hours.’

Schools are currently scheduled to operate fully online in all major cities of Georgia and the entire Adjara region until at least 25 November.

This article was prepared with support from the Friedrich-Ebert-Stiftung (FES) Regional Office in the South Caucasus. All opinions expressed are the author’s alone, and do not necessarily reflect the views of FES.