Vulnerable and divided: the uncertain state of the Circassian language

14 March marks the Day of Circassian Language and Writing, yet the language faces many serious challenges, including a lack of official support.

It was on this day in 1853 that the first Circassian language textbook, by famous Adygea educator Umar Bersey, was published in Tbilisi.

Circassian is an indigenous language of the Caucasus, closely related to the Abkhaz language. It has a rich consonant inventory — up to 60 sounds depending on the dialect — and a complex structure, where a single word can correspond to a whole sentence of Russian.

Today, Circassian is divided into two literary standards — Adyghe, spoken primarily by Circassians in Adygea and Krasnodar Krai, and Kabardian, in Karachay–Cherkessia and Kabardino-Balkaria. Despite differences, native speakers consider Adyghe and Kabardian to be parts of a common Circassian language.

UNESCO considers the Circassian language, like many other Caucasian languages, to be vulnerable.

Canceling mandatory Circassian classes

In January 2007, the Supreme Court of Adygea overruled the compulsory teaching of Circassian in the republic’s schools, which was introduced back in 2000. This has exacerbated the already difficult position of the language.

Both Russian and Circassian are official state languages in Adygea, but ethnic Circassians make up only 26% of the population.

The court ruled that it was unlawful to force students to study Circassian if they do not wish to, (even for ethnic Circassians). The issue was reportedly initially raised by the parents of students who were forced to study Circassian in schools.

This is a sentiment echoed by Russian President Vladimir Putin, who in July 2017 said it was unacceptable to force someone to study a language that was not their native tongue thereby opposing the compulsory study of state languages within the national republics. After this, inspections were carried out in many republics to check for violations of this rule.

Circassian as a second class language

Zaurbiy Chundyshko, Chairman of the Maykop Circassian Council, told OC Media that Circassian is in a difficult situation. One of the main problems, according to him, is the reduction in the number of hours allocated for language learning in schools.

His public organisation demanded at the end of 2016 that the authorities in Adygea pass a law on the study and preservation of the Circassian language.

‘Another question is why our local authorities do not adopt it. Why? For us this remains unclear’, he says.

Chundyshko said that the local authorities simply point to the fact that Circassian, along with Russian, is already an official state language in Adygea, and claim teaching hours of Circassian provided for by the Ministry of Education of Russia and Adygea, are completed in full.

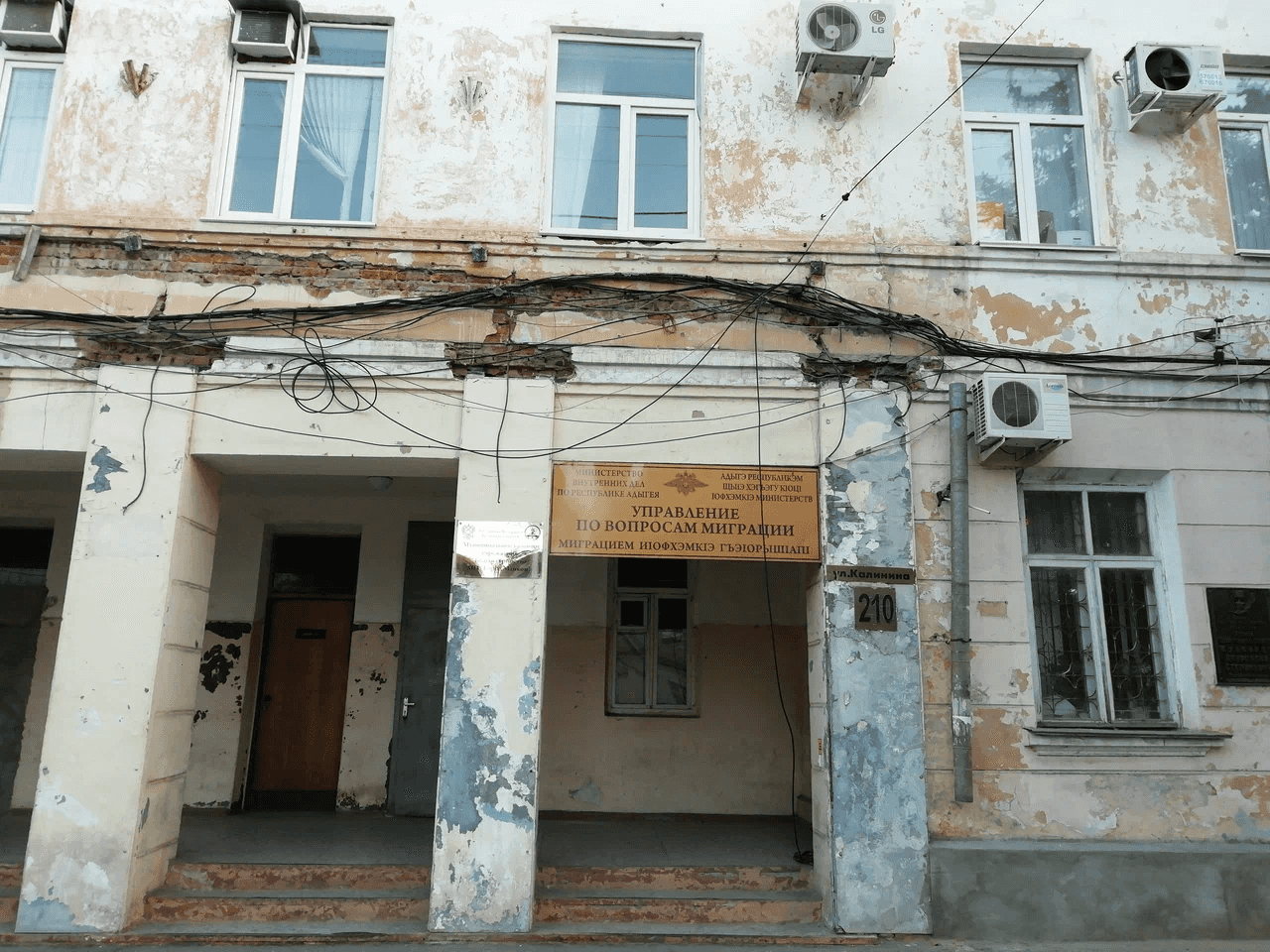

He says that despite the authorities claiming to fulfil the requirement to use Circassian within all institutions in the republic, official records and documents are kept only in Russian.

Chundyshko said that on the eve of the Day of the Circassian language, 14 March, his organisation plans to again demand the authorities pass a law on Circassian language.

Attempts to save the language

Former director of Adygeya’s Institute of Humanitarian Studies, and a prominent Circassian scientist and linguist, professor Batyrbiy Bersirov, says that the teaching of Circassian language is in trouble. He notes that interest in studying the language in universities has dropped off dramatically in the last 2–3 years, and that in the humanitarian faculties, interest in Circassian has also decreased.

According to him, there are no primary schools where instruction is conducted solely in Circassian, and the level of training of school teachers in Circassian is alarming.

‘We, at the level of the Institute for Humanitarian Studies, the Ministry of Education, the public, are trying to intensify work with students in schools, to interest them in going to study at the Faculty of Adyghe Cultural Philology after graduating from school’, Bersirov says.

According to the latest data from Adygea’s Ministry of Education and Science, there are 148 schools in the republic, with around 50,000 pupils. Only 34 of these offer any lessons on Circassian language and literature.

Although the situation is difficult, a newspaper, in Circassian, Adyg Voice, is regularly published, as well as magazines and scientific bulletins at universities.

‘Functionally, the Circassian language fulfills its duties. In addition, now there is a lot going on to prepare federal textbooks’, Bersirov explains.

Spoken only at home

A number of pre-schools in the city of Maykop now hold Circassian language circles, Asya Shevotsukova, who works in a kindergarten in Adygea, told OC Media.

‘We have a Circassian language circle in the kindergarten, but there is not much time dedicated to that. And not all children can visit this circle. Only a certain number — 15 children’, she said

Shevotsukova said there are more people wishing to join the circle than there are spots available. In addition, the circle gathers only twice a week for half an hour.

‘If in families they speak their native language, then this is a big plus. But very few people do this’, she said.

She is echoed by Fatima Pshizova, an office worker in a company in Adygea. ‘The position of our native language is certainly not the best, but all because we are less likely to speak in our native language. Even among relatives. Most likely, we ourselves are to blame for this’, she tells OC Media.

Fatima says that two months ago she got a new job and most of all she was surprised that in a fairly large group, everyone talks to each other only in Circassian. ‘It’s so cool!’ she exclaims.

Zhambot (who did not wish to reveal his surname), a philologist from Kabardino-Balkaria, says that it is not enough to speak the language at home. If the native language is used only at a household level, this means that only simple expressions and sentences are used. And this, according to Zhambot, is not enough to preserve the language.

‘To understand how much our level of Circassian language has dropped, I suggest that everyone in doubt listen to old Circassian songs. In general, where do the words come from? They come with new developments, changes in life’, he said.

Zhambot says there are young writers to be found, but that they do not see the prospect of being published and must find a job doing something else to feed their families.

‘We have very few magazines in our native language, we do not have a lot of programmes on Circassian themes, we do not have our own television station, very few young authors are published in their native language. And as you know, writers are indicators of the state of society at one time or another’, Zhambot concludes. He adds that on the Internet, there is practically no information in Circassian.

A united Circassian language

Speaking about the problems of the Circassian language, it’s impossible to get around the issue of unifying and creating a single alphabet for Adyghe and Kabardian literary standards, which has been discussed for several decades. Some are in favor of using a Latin alphabet, some are for the Cyrillic alphabet, and some advocate a hieroglyphic alphabet based on ancient Circassian tamgas. Given almost all written Circassian uses the Cyrillic alphabet, switching to another alphabet would be challenging.

However, some experts say that none of these options are suitable for the Circassian language, since they do not fully reflect the phonetic features of the language.

Ruslan Kesh, coordinator of the public movement the Circassian Union in Kabardino-Balkaria, says it is first necessary to formulate the principles of a single literary language, and only then discuss the problem of a single alphabet. He argues that it’s already possible to fix the existing alphabets, to make sure that the same sounds are not indicated by different symbols.

‘For example, the same sound in Eastern and Western dialects are often indicated in different ways. This should be solved now’, he explains. The next step, according to Kesh, is to unite the dialects, instead of replacing one with another. This, he says, will increase the wealth of the language.

‘Then, from the different ways words are formed, one should choose the simplest, and afterwards approve a single literary form of pronunciation of words’, he says.

Only after that will the way for a single literary alphabet be opened, Kesh says.