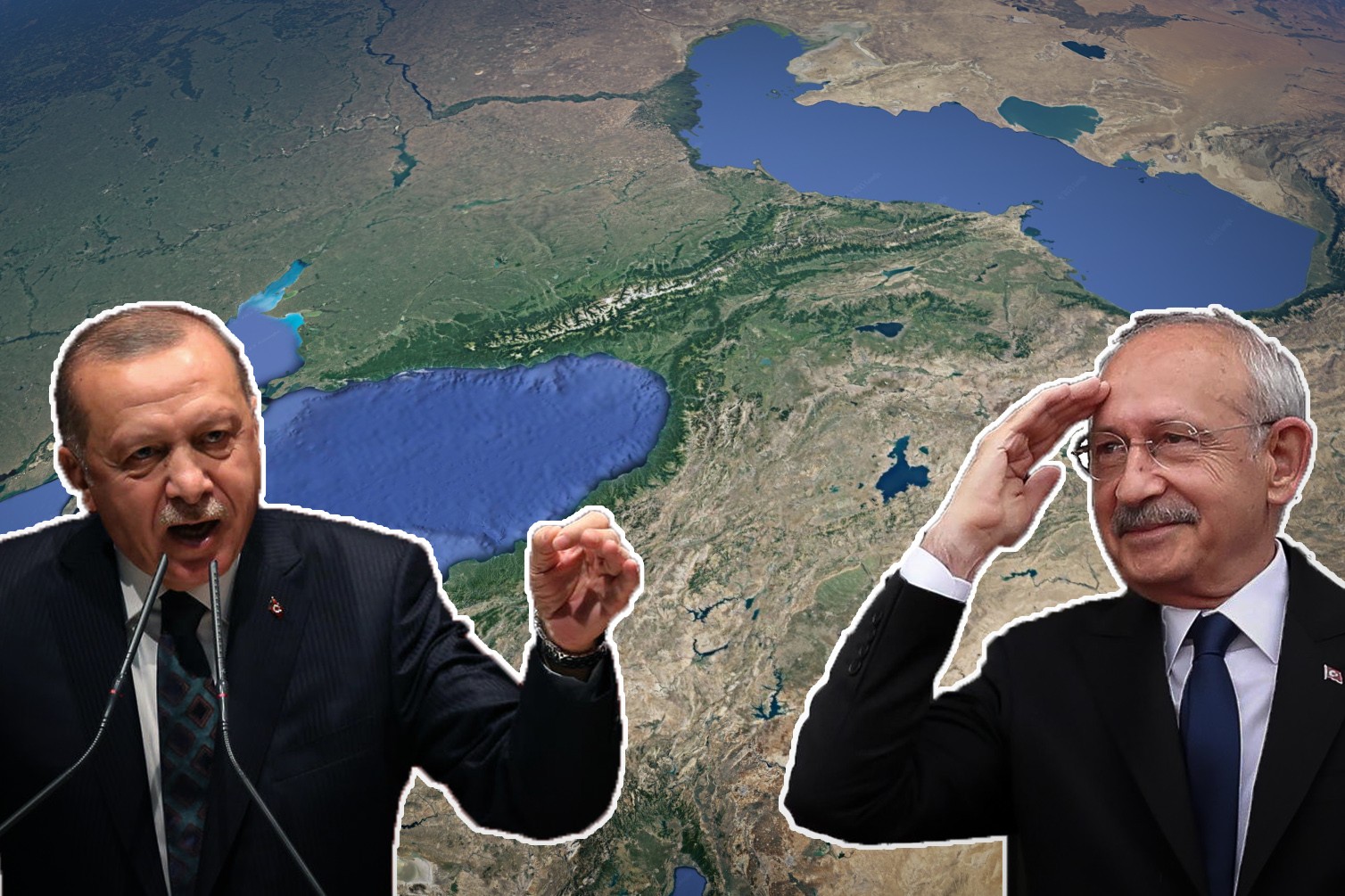

Turkey’s elections threaten to dislodge President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan after two decades in power. Amongst the country’s neighbours in the South Caucasus, the impact of such a turn of events could have vastly differing impacts.

Turkey’s parliamentary and presidential elections on 14 May will see President Recep Tayyip Erdoğan face his biggest challenge in years, facing an opposition alliance headed by Kemal Kılıcdaroğlu.

Given Turkey’s geographical proximity and geopolitical influence in the region, the country unsurprisingly looms large in the South Caucasus — whether in its close ties with and military support for Azerbaijan, which considers Turkey to be a ‘fraternal nation’, trading ties and political cooperation with Georgia, or an increasingly tense relationship with Armenia.

A change in Turkey’s political trajectory could potentially shift the country’s political positions, international ties, and security positions in a way that could significantly reshape the political landscape of the South Caucasus.

Azerbaijan: ‘Rushing to reach a peace treaty’

Azerbaijan, with its shared cultural and linguistic roots, has long been the closest nation in the South Caucasus to Turkey, so much so that the slogan ‘two states one nation’ has been coined to describe the pair.

As such Richard Giragosian, the director of the Regional Studies Center think-tank in Yerevan, tells OC Media that the elections are a ‘great worry’ for Azerbaijan.

He says that this is evident in Azerbaijan’s ‘rush’ to conclude a peace treaty with Armenia, before the potential loss of Erdoğan’s ‘guaranteed blind support and backing for his Azerbaijani counterpart’.

More than 11,000 Turkish citizens living in Azerbaijan are eligible to vote in the elections on Sunday, at polling stations in regions throughout the country, and since April, Azerbaijani pro-government media has been publishing material supporting Erdoğan’s bid for a third term.

It focuses on the idea of Azerbaijan and Turkey having jointly flourished due to the close cooperation between Erdoğan and Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev, as well as Turkey’s support for Azerbaijan in the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War.

This marks a distinct shift in the official Azerbaijani position on Turkey’s politics: while Baku has previously asserted that ‘Turkey’s choice is our choice’, a position it maintained throughout the past 30 years, the government has now openly shown its support for Erdoğan in pro-government media, and criticised those who oppose him.

Kemal Kılıçdaroğlu, the candidate backed by a six-party opposition alliance and the chair of the Republican Movement Party, also provoked Baku’s ire with his campaign promise that he would set up a modern ‘Silk Road’ trade and transport corridor from Turkey to China. His description of the route named Iran, Turkmenistan, Uzbekistan, and Kazakhstan, but neglected to mention Azerbaijan.

Speaking on 10 May, Azerbaijan’s President Ilham Aliyev spoke out against ‘those who want to exclude Azerbaijan’, and stated that Azerbaijan was a key transport centre in Eurasia on the Europe–Caucasus–Asia Middle Corridor.

However, the key concern of many in the region remains the impact the elections might have on the Azerbaijan–Armenia conflict and Nagorno-Karabakh.

Speaking to OC Media, independent Azerbaijani opposition politician and director of the Institute of Political Management, Azer Gasimli suggests that in the case of an Erdoğan win, the Russian peacekeeping force would remain in place, maintaining an indirect struggle for influence between Russia and Turkey in the region. However, in the event of an opposition win, Gasimli believes Turkey will reestablish communication with Armenia and the West, and so foster trilateral relations between Armenia, Azerbaijan, and Turkey.

‘The Caucasus region needs this type of cooperation’, says Gasimli. ‘I think that choosing Kılıçdaroğlu is more suitable for our region in terms of security, conflict, and economic development.’

However, he warns that Aliyev would oppose such a political shift, noting that the potential for such action is already evident both in the suspension of Turkey’s government-critical FOX TV within Azerbaijan in 2017, and shifts in the government’s rhetoric regarding the elections.

Gasimli concludes that Azerbaijan’s relationship with Erdoğan will ‘improve’ if he remains in power, but that a change in leadership is likely to prompt a cooling in relations.

He adds that he does not imagine Azerbaijani people will change their attitude towards Turkey in the case of a change of power.

‘However, the government will try to form a dual opinion against Turkey in the population and adapt the formation of opinion against Turkey to dual standards’, he says.

Ali Karimli, chair of Azerbaijan’s opposition Popular Front Party, wrote that Aliyev understood that ‘the Putin government, which has always supported it, is currently involved in its own crisis’.

He added that the Azerbaijani president ‘unequivocally taking sides’ in the run-up to the election was ‘completely wrong’.

‘Undoubtedly, this is also based on widespread corruption. Because uncovering the corrupt cooperation between Aliyev and Erdoğan is not useful for Aliyev’, wrote Karimli.

However, Zardusht Alizade, an Azerbaijani political analyst, conflict specialist, and former opposition politician based in Baku told OC Media that a change in Turkey’s relations with Azerbaijan could also be politically risky within Turkey itself.

‘The Erdoğan–Aliyev couple has created propaganda in such a way that Turkish public consciousness considers Azerbaijan’s victory in the war as Turkey’s victory, and the people will not forgive any Turkish government or political figure who refuses this useful factor’, says Alizadeh.

Armenia: A return to diplomatic ‘normalcy’

While direct diplomatic relations between Turkey and Armenia have been cut since 1993, tensions between the two countries have risen further still in recent weeks.

Last week, Turkey closed its airspace to Armenian planes in response to the unveiling of a statue commemorating Operation Nemesis, a programme to assassinate the perpetrators of the Armenian genocide. A few days later, Turkish Foreign Minister Mevlüt Çavuşoğlu threatened to halt negotiations on normalising relations with Armenia if the country refused to demolish it.

Tensions between the two countries have historically been fueled by disagreements regarding the genocide of the Ottoman Empire’s Armenian population, which Turkey does not recognise, and Turkey’s support for Azerbaijan in the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict. Turkey has explicitly tied the normalisation of relations with Armenia to the resolution of the Nagorno-Karabakh conflict, a position which Armenia has implicitly refused through its assertion that normalisation should be ‘unconditional’.

[Read more: Armenia’s Foreign Minister makes ‘historic’ visit to Turkey]

The Regional Studies Center’s Richard Giragosian believes that a shift in power in Turkey will mostly affect Armenia indirectly, through its effects on Azerbaijan.

‘The process of normalisation will continue, no matter who wins, with only slight variance or deviation in style but not substance in Turkey’s approach toward Armenia’, says Giragosian.

Turkey and Armenia previously attempted to normalise their relations in 2008 during the presidency of Abdullah Gül, when current president Erdoğan was serving as the country’s prime minister. Despite intense talks and reports of progress, the attempt failed, with no resumption of negotiations until the end of the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War.

However, Giragosian believes that an opposition win could affect Turkey’s broader foreign policy, and so its interactions with Armenia’s international partners.

‘The possible return of the opposition will likely return a degree of “normalcy” in Turkish foreign policy, reverting to its traditional ties to the West, and with the United States and NATO in particular, and embarking on a “course correction” in the Turkish relationship with Russia, moving Ankara much further away from Moscow’, says Giragosian.

Regardless of outcome, the reprecussions of the election on Armenia, including the economic impact, Giragosian says, are likely to be little to none. Armenia banned the import of Turkish products after the Second Nagorno-Karabakh War, early in 2021, but lifted the ban a year after, as the Armenian market struggled to find alternatives and the countries intensified talks on normalising relations and opening their shared border to citizens of third countries.

While some Turkish products are widespread in Armenia, their trade is conducted through Georgia, avoiding direct economic relations between Armenia and Turkey, and is unlikely to be affected by a change of political alignment.

Georgia: ‘Only cosmetic changes’

The Georgian political experts and economists that OC Media spoke to were unanimous in their assessment that, no matter the outcome of the election, dramatic changes in Georgia and Turkey’s relations should not be expected.

However, Kornely Kakachia, the founder of the Georgian Institute of Politics, told OC Media that while he anticipated only ‘cosmetic changes in foreign policy’ an opposition win, and corresponding change in Turkey’s relationship to NATO and the European Union, could have a significant impact on Georgia.

‘The role of Turkey is very important for Georgia, especially when there is an aggressive Russia in our neighbourhood’, says Kakachia. ‘It is very important that we have strategic relations with Turkey, a member of NATO, because, in case of any complications, it could potentially play an important role’.

He adds that the Erdoğan government has formally supported Georgia joining NATO.

However, Kakachia notes that Turkey’s image has suffered both within Georgia and internationally as a result of Erdoğan’s ‘autocratic tendencies’.

‘If until now Turkey was thought of as a NATO member country, a part of the West, during the period of his rule, this idea is increasingly doubted, and today’s Turkey is seen from Tbilisi not as a part of the Western world, but as a Middle Eastern power state, which has slightly changed the image of Turkey in Georgia’.

He suggests that if Erdoğan loses the election, the opposition might try to improve transatlantic relations and get closer to the European Union, with the latter potentially playing ‘an important role’ in Georgia’s participation in European projects.

Paata Aroshidze, an associate professor of economics at Shota Rustaveli State University of Batumi, told OC Media that a Kılıçdaroğlu victory would not change economic relations between the two countries.

Aroshidze notes that Turkey has often been Georgia’s largest trade partner.

‘The main connection between us is the energy partnership and the joint involvement of Georgia and Turkey in international projects, which NATO and the European Union strengthen’, says Aroshidze.

‘[In terms of strategic partnership], I cannot say that anything will change if Erdoğan stays or his opponent comes, because the oil supply of not one or two countries, but the whole of Europe, depends on [joint] energy projects’.

He also draws attention to the visa-free regime between Georgia and Turkey, and the fact that large numbers of Georgian citizens are employed in Turkey which, according to him, is another example of how important economic relations between the two countries are.

Kakachia summarises his view on the matter succinctly.

‘Turkey has always been pragmatic in relation to Georgia’, adds Kakachia. ‘These good neighbourly relations will probably remain [no matter who wins]’.