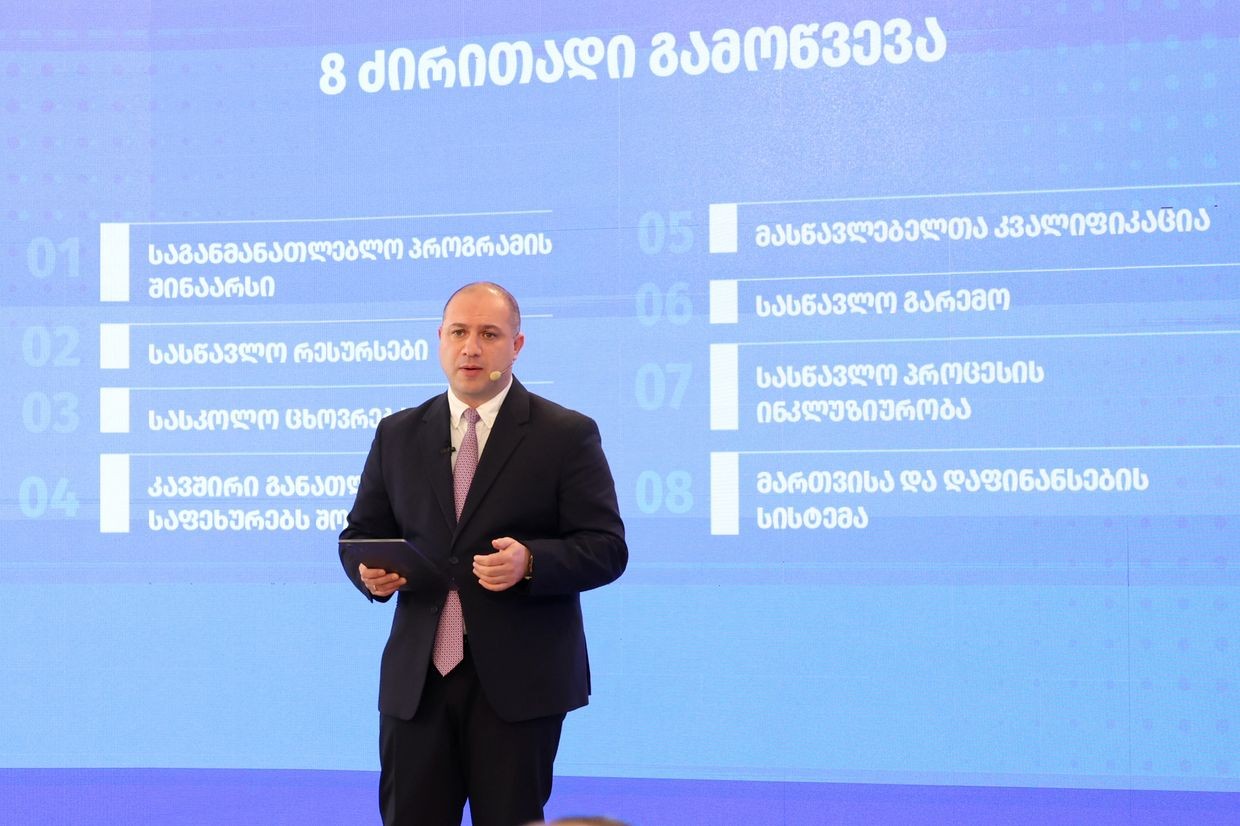

Georgian Education Minister Givi Mikanadze has presented an upcoming education reform, featuring school textbooks prepared by specialists selected by the ministry, making year 12 optional, and introducing school uniforms for primary school students.

Mikanadze presented the proposed reforms on Tuesday, outlining ‘eight main challenges’ school education currently faces. These included the content of the curriculum and educational resources, as well as the issue of harmonisation between different levels of education and teachers’ qualifications.

‘The existing system cannot ensure the full development of young people who possess civic responsibility, adequate competitiveness, and specific interests’, he added.

Mikanadze pointed to the 2004 document on national education goals, adopted by the formerly ruling United national Movement (UNM), as one of the causes of the problem. He claimed the document was ‘saturated with liberal values’, and stressed that the new version approved in 2024 is based on a ‘patriotic spirit’, with the reform’s objectives drawn from it.

According to Mikanadze, the reform will change the current system for preparing school textbooks. Until now, various groups of authors worked with different publishers, submitted their textbooks to the ministry, and specialist review panels evaluated them before they received ministry approval.

Under the current system, schools were able to choose between several ministry-approved textbooks for each subject and year. Under the new model, the ministry itself will produce the textbooks through ‘experts’ it selects, under a ‘one book in all schools’ principle.

Discussing the reasons for the change, Mikanadze argued that under the current model — where ‘children in the same year and same subject study from different textbooks in different schools’ — uniformity is lacking, making it impossible to properly assess the quality of their education.

‘We will replace all school textbooks within two to three years […] The ministry will take responsibility for writing them’, he added.

Mikanadze additionally announced that only children who have reached the age of six will be allowed into primary school, citing the possible social-emotional unpreparedness of younger students. He also said that the ministry intends to bring back the long-discontinued school uniforms for years 1–6, and that students will be prohibited from using mobile phones during lessons.

‘A balance will be maintained so that the learning process is not disrupted, but the child’s ability to communicate, with their parents or someone important to them, is not cut off’, he added when speaking about the phone ban.

During the presentation, Mikanadze also addressed the government’s decision to shift to an 11-year schooling model — a move already criticised by many, who argued that it would deprive Georgian graduates of the opportunity to pursue university studies in the EU and the US, where primary and secondary education typically lasts a total of 12 years.

Saying that the critics’ claims were ‘speculative’ and ‘unconvincing’, Mikanadze noted that the 12th year would not be fully abolished but would become voluntary.

‘Every March, we will open a registration system where anyone interested can sign up if they wish to study in the 12th grade. For them, the 12th grade will be opened specifically in the following academic year’, he said.

Among other points, Mikanadze also highlighted the need to strengthen the ‘non-formal education’ component, noting that existing projects should be maintained and expanded. These included a programme launched this year by the ministry together with the Patriarchate of the Georgian Orthodox Church, which Mikanadze said teaches children ‘love of the homeland, life values, friendship’.

He added that joint projects with the Interior Ministry and the Defence Ministry should also be expanded. In particular, he mentioned anti-drug campaigns in schools and ‘army lessons’, which have already been introduced in ‘more than 150 schools’ in 2025 which teach students ‘military spirit and patriotism-based programmes’.

Some components of the reforms presented received almost immediate criticism following Mikanadze’s presentation

The president of the International Publisher’s Association (IPA), Gvantsa Jobava, criticised the government’s plan to produce school textbooks, calling the move a ‘return to the Soviet past’ and an attempt by the government to control textbook contents.

‘Why should it be surprising that a regime that tries daily to submit our country to Russia’s grasp […] wants to control schools even more — not just teachers, but students’ minds, to limit the development of independent thinking as much as possible’, she added.

Before the presentation of the school education reform, the government approved a higher education reform, which also drew criticism over its potential consequences, announced amidst the ruling party’s growing hostility toward dissent in academia.