Georgia’s energy sector is leaking money — into Russian coffers

Strategic energy projects remain stalled or abandoned with millions instead going to pay arbitration disputes led by Russia and Turkey.

On the last day of 2025, Georgia began making payments under an international arbitration penalty in favour of Inter RAO, one of Russia’s largest public energy companies. According to the agreed upon schedule, Georgia will make seven payments between December 2025 and July 2028 totalling $139 million, including interest.

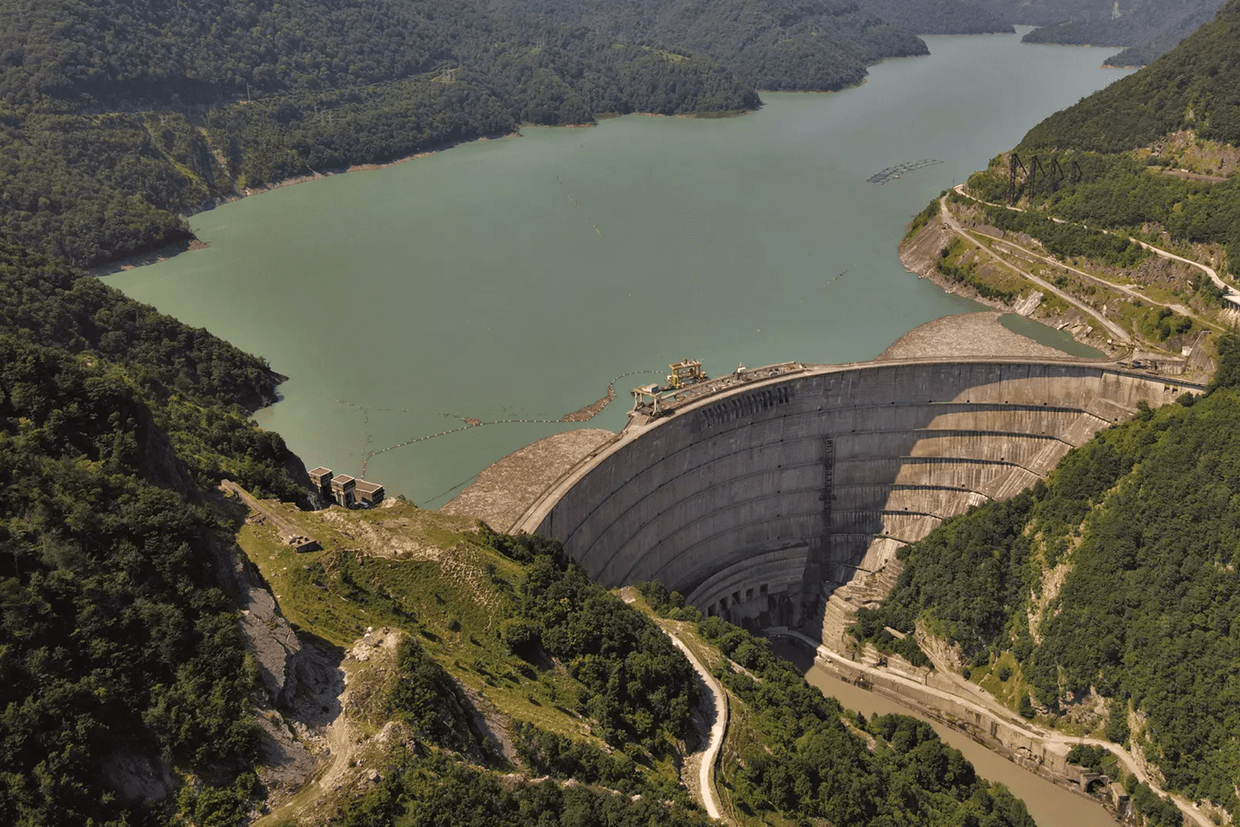

At the heart of the dispute lies a tariff policy failure rooted in contradictory government commitments. Inter RAO owns 75% of Telasi, Tbilisi’s electricity distribution company, and controls the hydropower plants (HPP) Khrami 1 and Khrami 2 through Dutch subsidiaries. These investments were protected under a bilateral investment treaty between Georgia and the Netherlands, as well as specific contractual guarantees.

In 2011, the Georgian government signed a memorandum guaranteeing that electricity tariffs would not be reduced for 15 years in exchange for investment in Tbilisi’s electricity infrastructure. In 2013, amid political pressure to reduce tariffs — a key electoral promise of the then-newly elected Georgian Dream party — a new memorandum was signed. Inter RAO agreed to tariff reductions, while the government promised that currency depreciation losses would be reflected in future tariffs until the end of 2025. That did not happen.

In 2014–2015, Georgia adopted a new tariff methodology that excluded currency depreciation. As a result, Telasi’s distribution tariffs and the Khrami HPP generation tariffs were calculated in violation of the 2013 memorandum. Inter RAO initiated arbitration in 2017, claiming $200 million in losses — a claim the tribunals largely upheld.

Following the final ruling in August 2025, energy experts and Georgia’s political opposition almost immediately unleashed a cascade of criticism against the government, arguing that they foresee similar blunders continuing to occur in this already vulnerable sector. Indeed, the case has come to symbolise deeper, long-standing problems in the country’s energy sector — marked by poor governance, contradictory policies, and a lack of strategic professionalism.

The government defended its stance in its usual style.

On 8 January, the head of Georgia’s Government Administration, Levan Zhorzholiani, appeared on Rustavi 2, casting blame on the government of now-imprisoned former president Mikheil Saakashvili. According to Zhorzholiani, despite their anti-Russian rhetoric, Saakashvili’s government acted in a pro-Russian manner by transferring strategic energy assets to Russian companies and committing the state to compensate them through higher electricity tariffs — a burden that would have fallen on the public.

For years, pro-government forces have claimed that it was Saakashvili who sold off major strategic energy facilities, including the transfer of the Khrami hydropower plants to Inter RAO.

Beyond playing the blame game, Georgian Dream officials have reassured the public that the enforcement of the arbitration decision will have a minimal, effectively zero, negative impact on Georgia’s economy and population. Indeed, a person close to Georgia’s energy projects and court proceedings, who asked to remain anonymous, emphasised that other projects with foreign companies will not be resolved so easily.

Mounting losses

The Inter RAO case is not an isolated failure. At the end of 2024, Georgia lost another major arbitration dispute with Enka Renewables over the Namakhvani hydropower project. The tribunal awarded $383.2 million, which, including interest, now exceeds $450 million.

Turkey’s Enka Insaat signed a deal in April 2019 to develop and operate the Namakhvani Cascade HPP project on the Rioni River — a project consisting of two hydropower plants and estimated to cost $750 million. The project triggered large-scale protests. Demonstrations spread to Tbilisi, with some critics questioning the sincerity and motivations of the protest movement. The project was ultimately abandoned.

Combined, the Inter RAO and Enka cases alone have cost Georgia close to half a billion dollars — a sum comparable to the investment required to build a major hydropower plant, a deep-sea port, or other strategic infrastructure. Instead, the funds will go toward compensating investors for projects that were never completed.

Former MP and former President of the National Bank of Georgia Roman Gotsiridze warns that Georgia faces up to $3.3 billion in potential arbitration liabilities. He has also criticised the lack of transparency surrounding these disputes and the high cost of legal representation. The Economic Ministry did not respond to OC Media’s request for comment.

‘To deal with cases it has mishandled, the Georgian government spent approximately ₾350 million ($130 million) solely on legal services for international arbitration disputes between 2016 and 2024’, Gotsiridze tells OC Media. ‘At present, claims totalling $3.3 billion are being brought against us in international arbitrations. Hundreds of millions have already been paid or are payable’.

According to Gotsiridze, the two cases already arbitrated, which feature effectively final decisions, were catastrophic.

‘The Inter RAO case is finalised and not subject to appeal. Regarding Namakhvani, we can dispute only procedural issues to buy time, but with almost 100% probability the outcome will not change’, he says. ‘$460 million — almost the amount needed to build Anaklia — has been lost’.

A systemic failure?

Energy analyst and Associate Professor at Ilia State University Murman Margvelashvili argues that the problem extends beyond individual cases and reflects a systemic failure of vision in Georgia’s energy policy.

‘Both the current and previous governments lacked a state-level strategic vision’, Margvelashvili tells OC Media. ‘Neither did anything truly significant happen in this area, except for reforms linked to Energy Community membership’.

The Energy Community ensures cooperation between the EU and member countries to achieve energy security, energy sustainability, and environmental goals. Georgia joined in 2017, and has since reached a 54% score of compliance.

Referring to the Namakhvani project, Margvelashvili described the process as chaotic and politicised.

‘There may have been outside forces and groups with their own commercial interests, but it was also clear that neither government was genuinely ready or interested in completing the project’, he says. ‘What happened there was simply unprofessionalism’.

He adds that the refusal to acknowledge and correct mistakes has cost the country dearly.

‘Time has been lost, imports are now our only option, and these losses are impossible to recover’, Margvelashvili says.

Strategic projects — including gas storage facilities, reservoir hydropower plants, modern thermal generation, and oil refining — remain stalled or abandoned, while Georgia’s dependence on energy imports continues to grow.

‘Everything that has happened confirms one conclusion’, Margvelashvili says. ‘No strategic energy projects are allowed to be completed in Georgia — gas, oil refining, hydropower. This leaves only one seriously interested party: Russia’.

According to Margvelashvili, the presence of large-scale investment or influence from other countries is something Russia seeks to limit. To achieve this, it often exploits religious narratives, which is why many far-right religious groups are perceived — and in many cases are — pro-Russian.

At the same time, Azerbaijan’s role as a transit partner has increased its economic influence in Georgia, while analysts say the country lacks sufficient diplomatic capacity to balance competing regional interests.

Indeed, the Anaklia Deep Sea Port currently remains idle, with its future unclear amidst shifting narratives about potential Chinese involvement. Despite repeated assurances from officials that the first ships will arrive ‘soon’, no concrete timeline has been provided.

‘We could have built a new port and a new hydropower plant with the $400 million we are now paying in fines’, Gotsiridze concludes.