‘He sold his soul’ — the North Caucasians going to war to make a living

Poverty and low wages make enlistment in Russia’s war in Ukraine a tempting offer for many in the North Caucasus.

‘I realised it was dangerous, but I would never have earned such money here. I decided to take a risk for the future of my loved ones’, Akhmed, a 28-year-old from Daghestan, says.

Akhmed asks for us to withhold his full name, citing fears he could be prosecuted for ‘discrediting the armed forces’ for giving an interview to a foreign publication. Indeed, any comments about the war in Ukraine that could be negatively construed can be seen as ‘discrediting the army’ in Russia, even interviews with pro-government media.

Akhmed grew up in a small village where employment was scarce. After finishing school, he scraped by on casual labour to help his family make ends meet — he was the eldest of six children, taking on the role of the head of the family after his father died.

When Russia launched its full-scale invasion of Ukraine in 2022, he did not want to go to war — his mother said she would ‘curse him’ if he disobeyed her and joined the army. However, Akhmed saw fellow villagers volunteering for the army, and their families told him that they were making good money.

In 2024, the local authorities announced a ₽1.5 million ($18,000) sign-up bonus for anyone enlisting. Akhmed saw this as a chance to improve his family’s material circumstances, and decided to talk to his mother again.

This time, she agreed. In the three years since the war began, their financial situation had deteriorated: his mother was forced into retirement and Akhmed was the only one with a regular income.

After signing a contract last November, Akhmed underwent two weeks of training before being sent to the front.

He says he calls home regularly, trying not to talk about the hardships of the service so as not to worry his family.

‘It’s not as bad as I thought it would be. But I’m lucky, I’m not involved in the assaults yet. Our unit isn’t suffering casualties like others. Most of all, I miss my little sisters. I hope I come back alive, for their sake at least’, Akhmed tells OC Media.

How much does a life cost?

Payments for signing military contracts as well as monthly salaries vary from region to region.

The federal government offers lump-sum payments of ₽400,000 ($4,900) for volunteers, with most regions adding to this in an apparent attempt to meet recruitment targets.

The highest payments in Russia are found in Samara, which offers sign up bonuses of ₽4 million ($49,000). In Daghestan, where Akhmed is from, the total sign-up bonus amounts to ₽1.6 million ($20,000), including money from both the regional and municipal authorities. Salaries for contract soldiers start from ₽204,000 ($2,500) per month.

Kabarda–Balkaria provides the highest payments in the region — ₽1.9 million ($23,000) on signing up and salaries starting at ₽210,000 ($2,600) per month.

Chechnya offers the lowest sign-up bonus in the North Caucasus — just ₽500,000 ($6,100). Monthly salaries start at just ₽100,000 ($1,200).Even this much can seem like a small fortune for people in the North Caucasus, where salaries are among the lowest in Russia, and the majority earn below $300 a month.

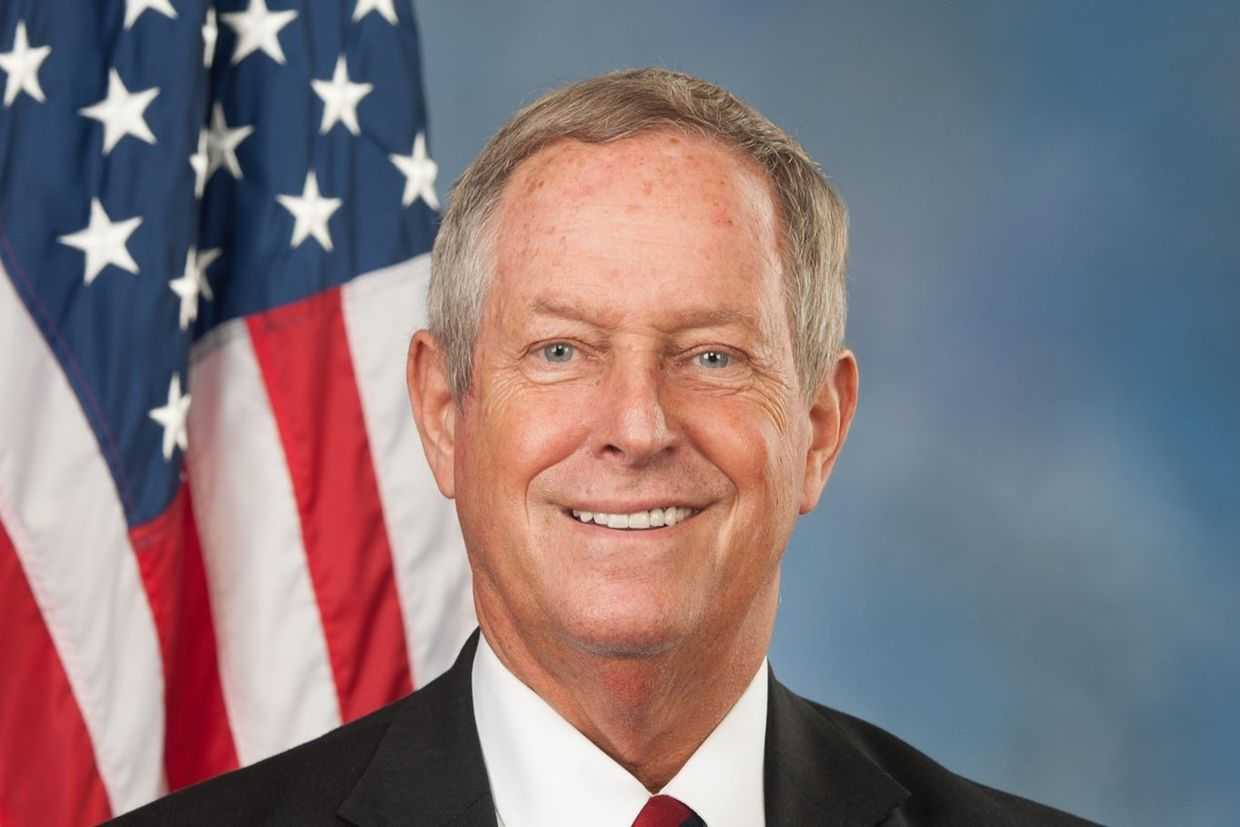

Alexander Alshinsky, an analyst from Farewell to Arms, a civil society organisation defending the rights of military deserters, agrees that financial incentives play a key role in attracting contract soldiers.

‘In regions with a low standard of living, the promised payments become a powerful incentive’, Alshinsky tells OC Media. ‘People see this as an opportunity to improve their financial situation, not always realising the risks and consequences’, he says.

Alshinsky notes that there is competition between the regions for attracting the most contract soldiers — this can be traced by official reports and statements of local authorities. In his opinion, regional heads fear punishment for not fulfilling the plan, so they try to show high results.

‘These “races for volunteers” began in the winter of 2022–2023 and continue until now. When one region announces a record amount of payments, after a while others start raising payments to keep up’, Alshinsky says.

Alshinsky emphasises that in the North Caucasus, all regions are subsidised and the standard of living is generally low. Therefore, local authorities believe that there is no need to offer high payments.

‘Besides, people do not always realise that it is possible to sign a contract in another region and get more money’, Alshinsky says.

Despite Russian citizens having the right to sign a contract in any region of Russia, most sign up at their place of residence or in Chechnya, where the Russian University of Special Forces is located.

Alshinsky says he is not surprised that people sign contracts in regions with low payments, such as in Chechnya, as many face administrative pressure — for example, being threatened with a criminal case.

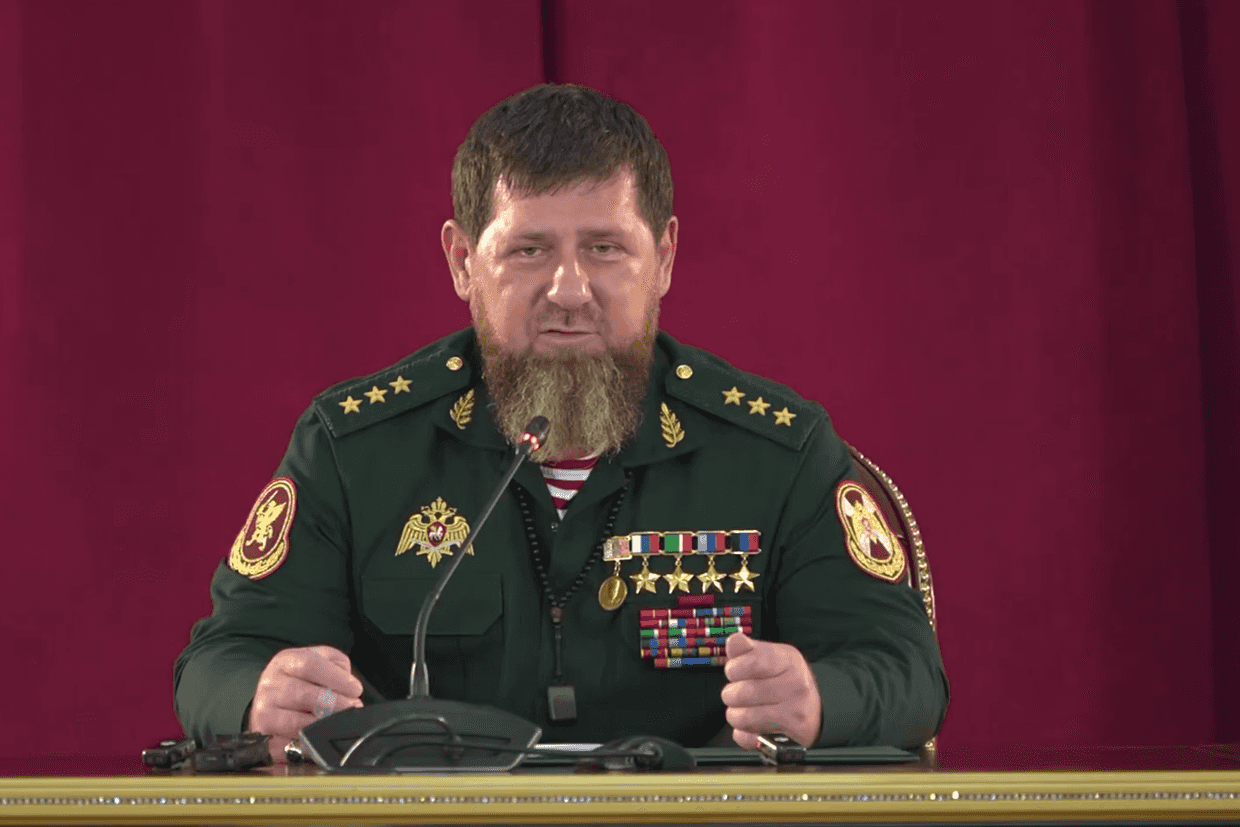

‘The Akhmat special forces in Gudermes is a separate case’, he says. ‘At the beginning of the war, people went there because, in addition to the standard payments, they were promised training and good supplies’.

‘Now it’s hard to say why they continue to go there. Perhaps it is habit or the reputation of the unit. There was a similar situation with Wagner — people went there expecting better supplies and different conditions of service’, Alshinsky notes.

‘He sold his soul’

Rooslan Totrov, a political scientist from North Ossetia, tells OC Media that the proliferation of advertising campaigns encouraging people to sign up as well as rising financial incentives indicates a lack of willing participants.

He concedes that while some volunteers are motivated by ideology, ‘the financial aspect in depressed regions is the decisive one’.

‘When you live in a deeply subsidised, depressed Russian region, where the median salary does not exceed ₽27,000–₽29,000 ($330–$350), and you’re promised ₽1 million ($12,000) immediately and a ₽200,000 ($2,400) salary — this is the ultimate social uplift’, Totrov says.

‘At the same time, people do not think that after service they will be able to occupy some privileged position, they think only about snatching ₽200,000 a month. This is an amount of money that none of these people has ever even held in their hands. If they had, they would not have gone to war’, Totrov says.

‘They don’t realise that they’re putting their lives on the line for a ridiculous sum of money, they don’t think that it could be cut short before the first monthly payment is made.’

When friends suggested 32-year-old Murat, a resident of Kabarda–Balkaria, sign a contract with the Russian military, he thought it would help provide for his family.

Murat used to work as a lorry driver, but due to economic difficulties, the company closed down and he was left without a job.

‘He said it wouldn’t last long, that he would soon come back with money and he could start living again’, recalls his mother, Zalina.

A few months later, Zalina received news of Murat’s death.

‘What do we need that money for now? What am I supposed to do with it? He sold his soul. I told him he wasn’t cut out for war, he was so quiet. Why would he go to war? He didn’t even do his [mandatory] military service’, Zalina says.

Now she and her daughter-in-law are raising Murat’s two children. According to her, in almost every family in their village, men are either missing or killed.

‘It’s just a catastrophe. How many children are without fathers now? God only knows’, Zalina says.

The exact number of Russian soldiers killed in Ukraine remains unknown. However, since the beginning of the war, RFE/RL journalists have found almost 13,000 obituaries dedicated to soldiers from southern Russia and the North Caucasus. The largest number have been from Daghestan.